FROM THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY TO GOOGLE MAPS.

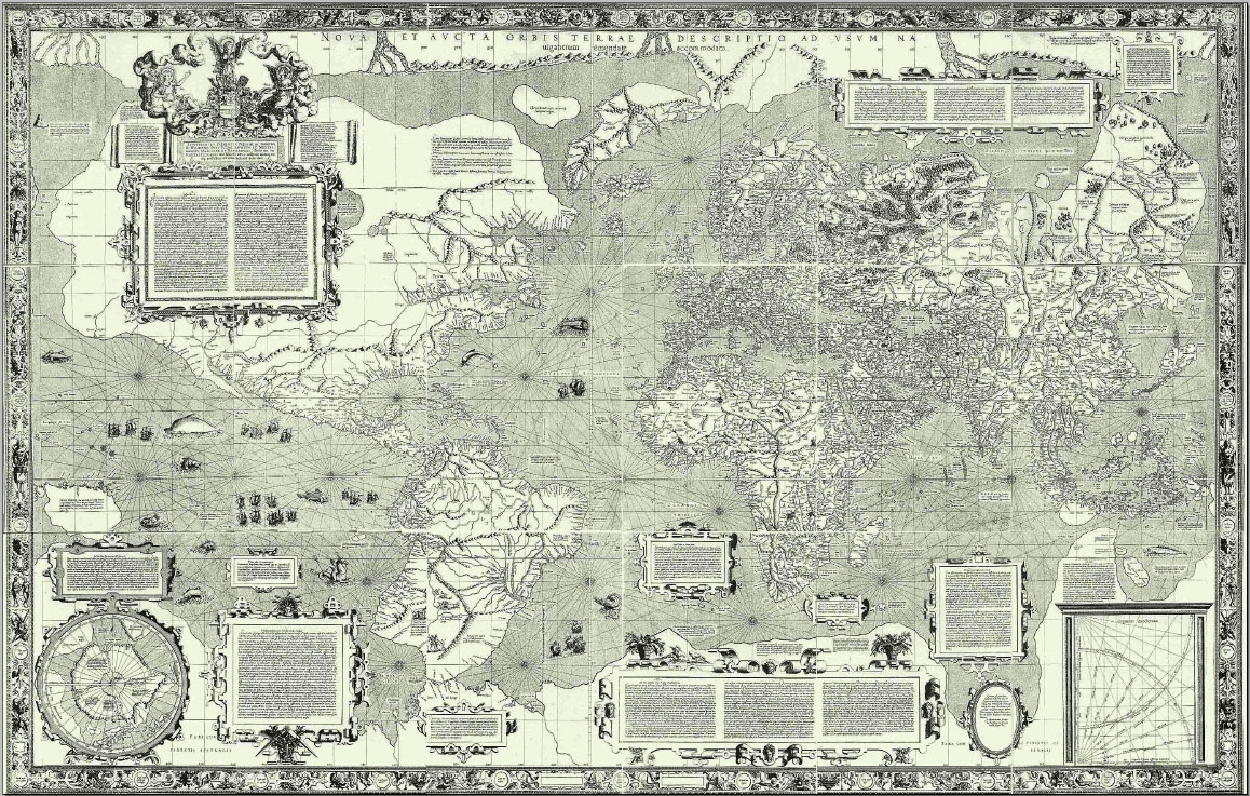

Gerardus Mercator’s world map dates from 1569. The scale is equal in all directions around any point, which keeps the angles and shapes of small objects intact. It worked really well for nautical navigation (which at that time was extremely important) because routes without changes of direction are straight, and consequently this projection became the standard. All map projections obviously distort the globe as they translate it to a flat surface, and the Mercator projection has a serious level of distortion the farther it moves from the equator. Greenland and Antarctica are quite substantial, to put it mildly. Europe is larger than it should be, which suited everyone back then.

Nevertheless, the projection has been a staple component of atlases until relatively recently. This site shows the Mercator-effect scale differences. Try it: goo.gl/7ks7hy

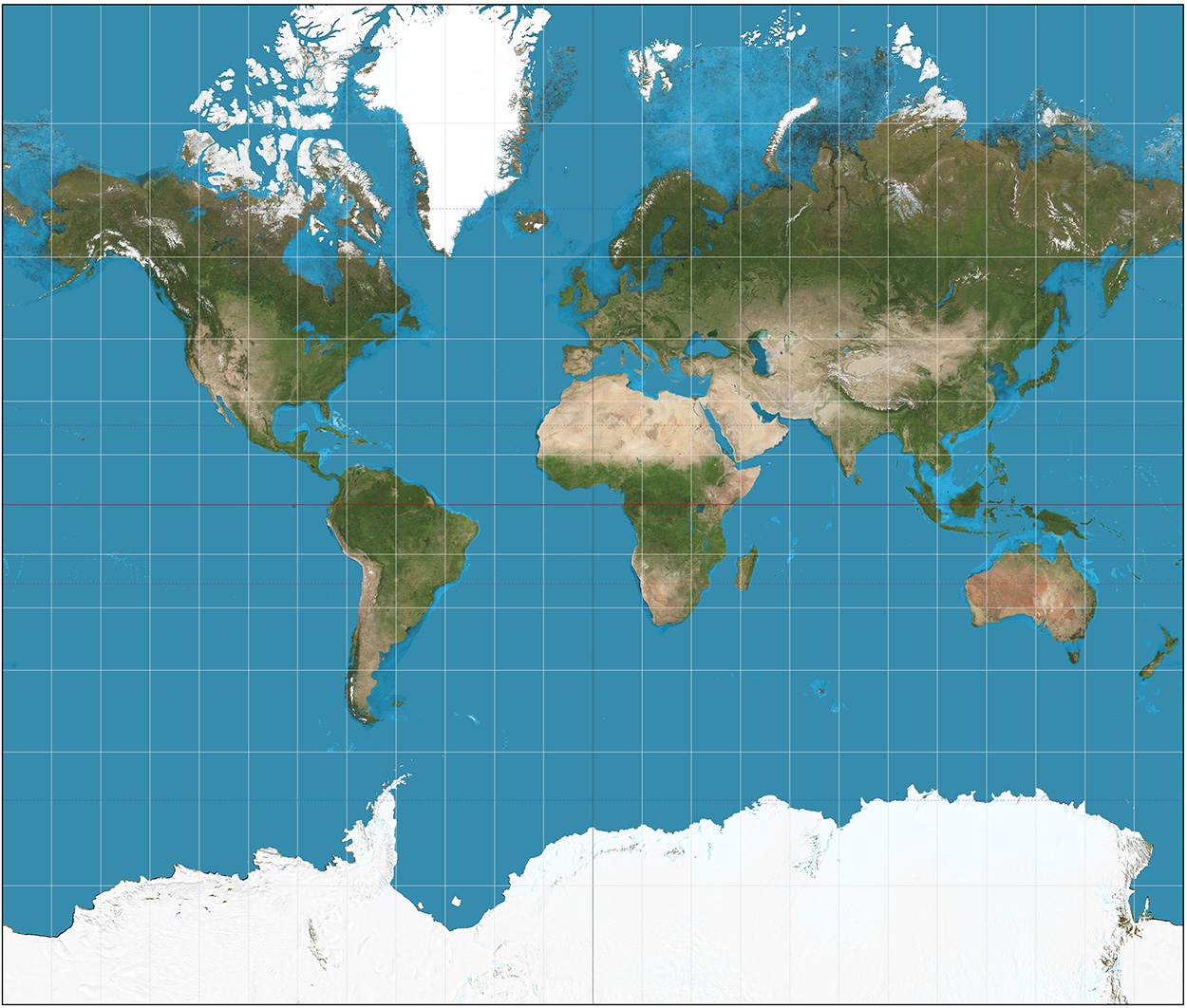

By contrast, the Gall-Peters projection accurately shows the relative size of land areas, but there’s considerable distortion, especially along the equator and at the poles. Also, like the Mercator, distances are not consistent. Consequently, many cartographers are not convinced that this is the way to go either. Nevertheless, UNESCO and UNICEF support this projection as a way of showing a fairer representation of the relative size of the developing countries.

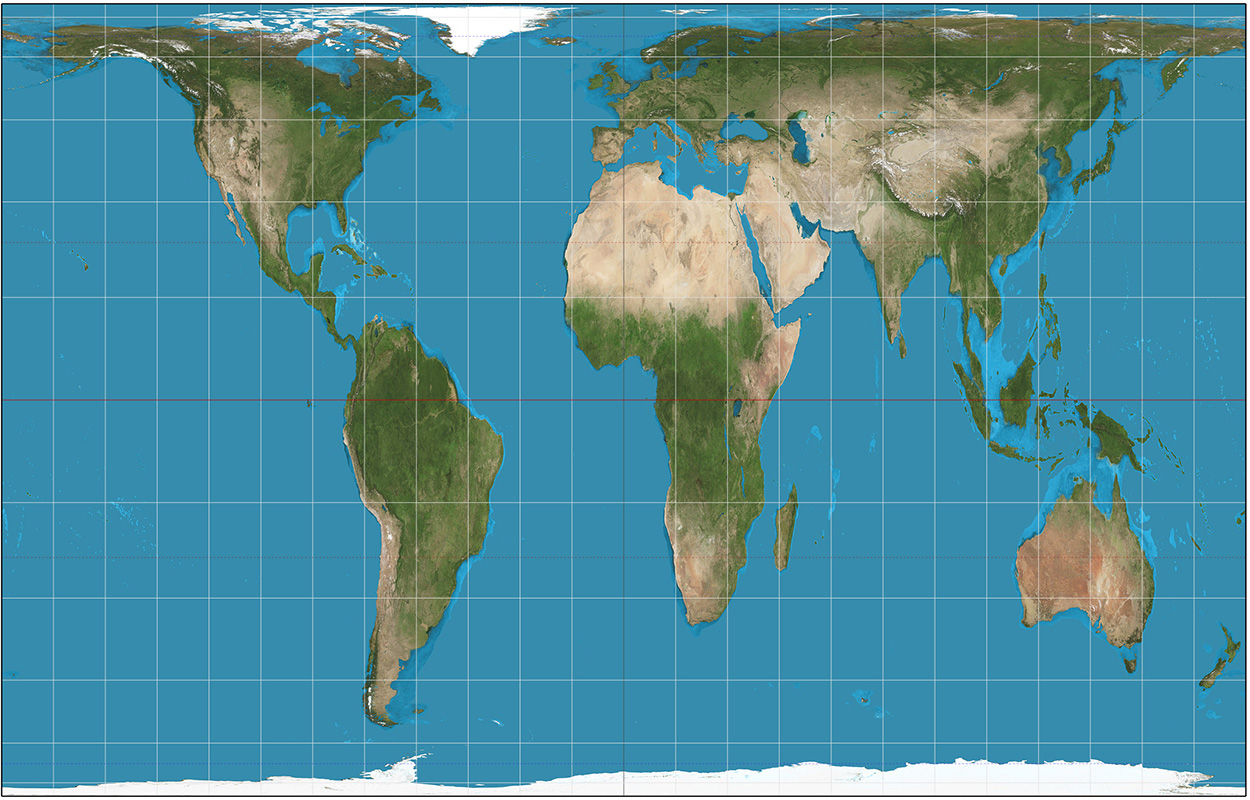

I’ve always liked the Robinson projection. It doesn’t tick all the boxes, but at least the land areas look something like they do on a globe.

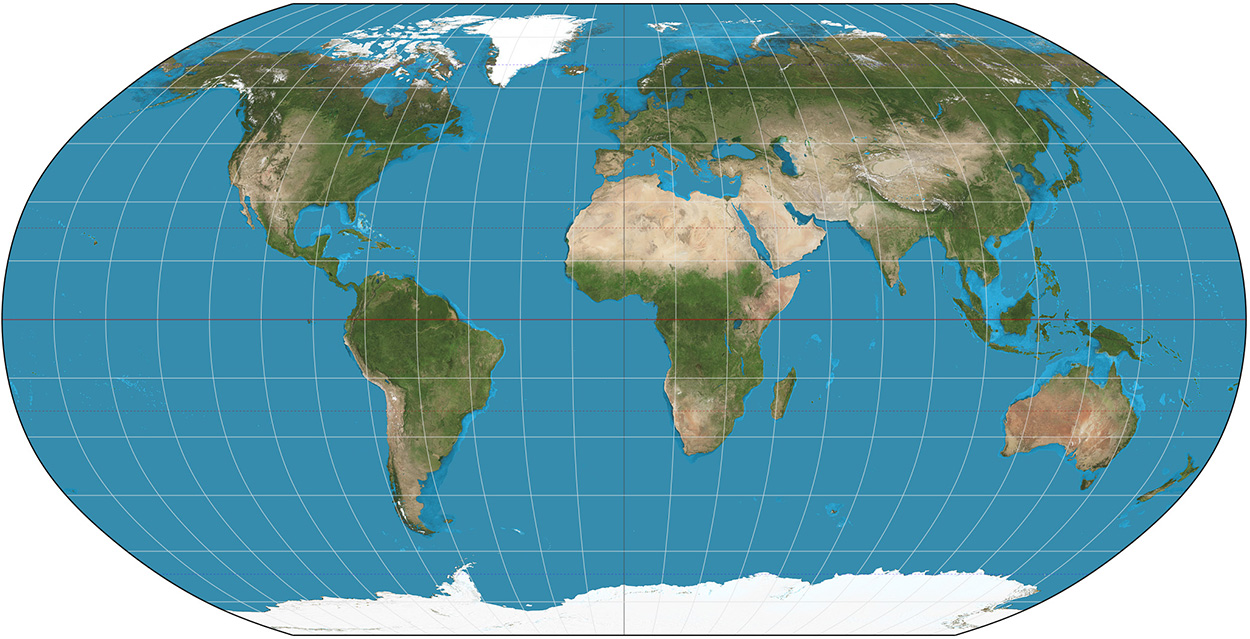

Many online applications (like Google Maps and OpenStreetMap) use a variant of the Mercator projection called Web Mercator. Why? Because with it’s parallel longitude and latitude lines, it scales really well from large-scale maps to local views, and north is always vertical. Distortion on a local scale is minimal. (I’ve been to the location below a lot in the last few years.)

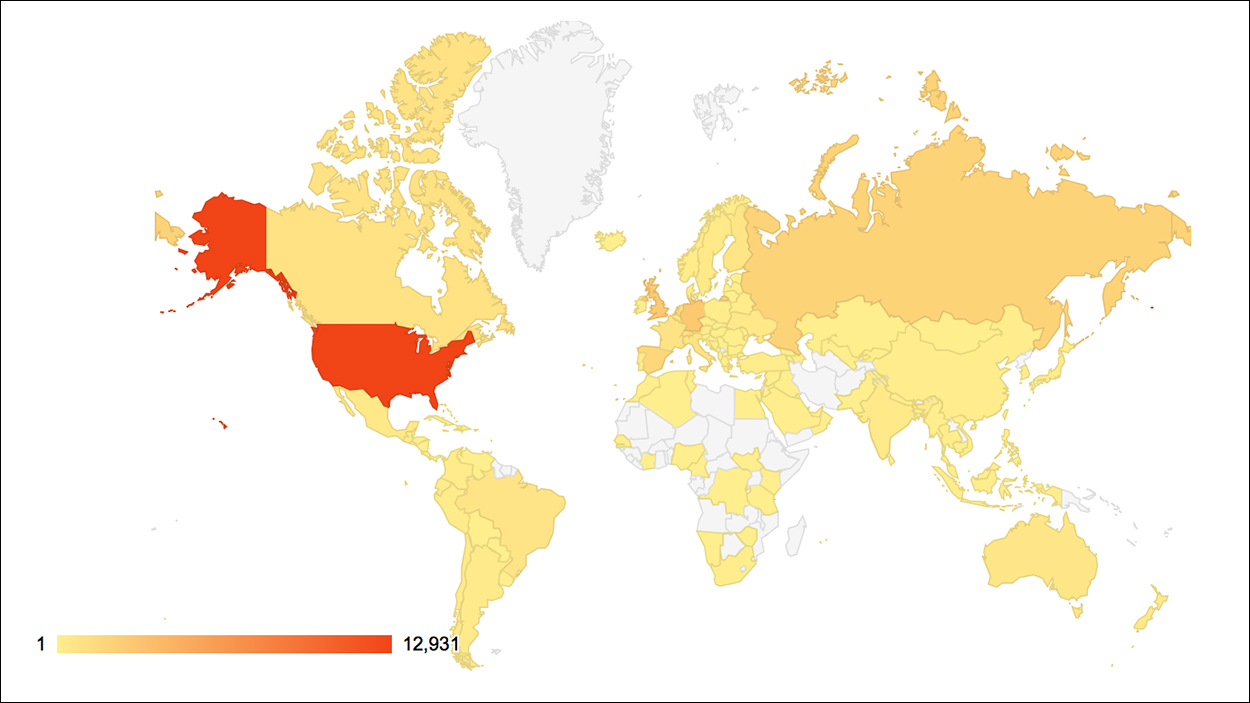

Here’s a WordPress map of views of this blog. No readers in super-sized Greenland. So far.

Mercator, Gall-Peters and Robinson images by Strebe.