RECREATING A MASTERPIECE, THE EASY WAY.

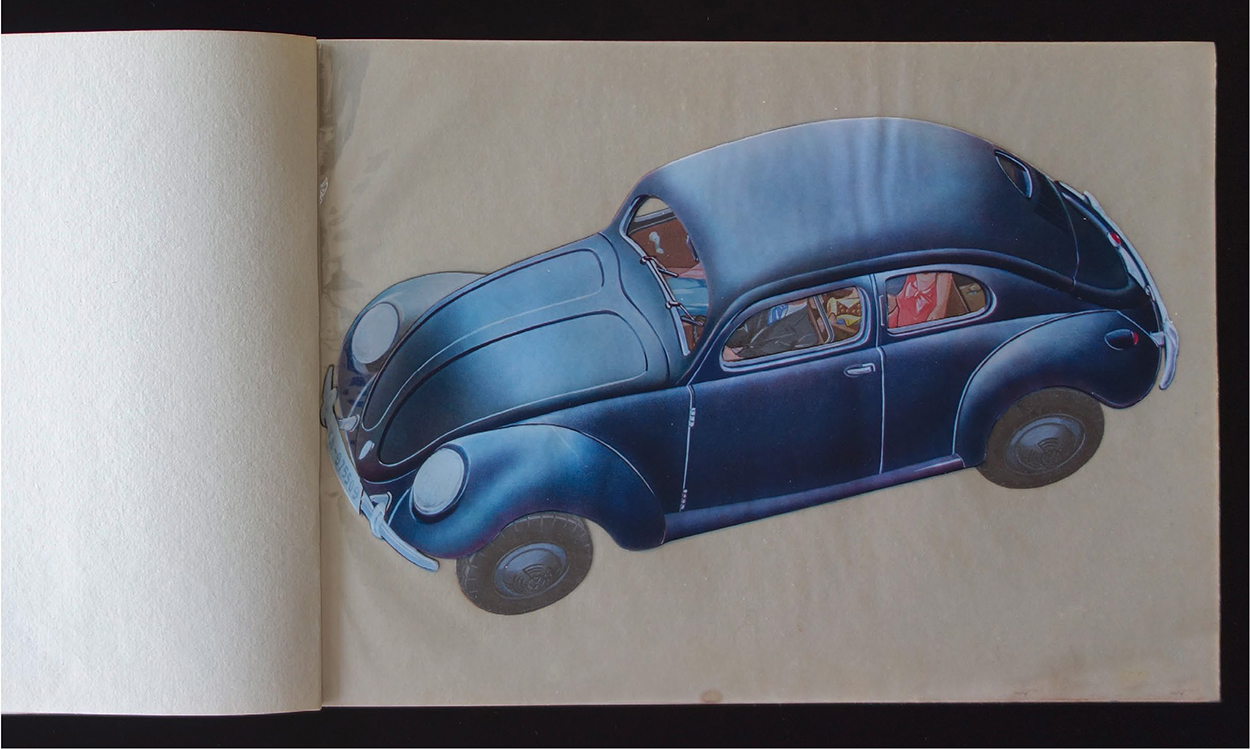

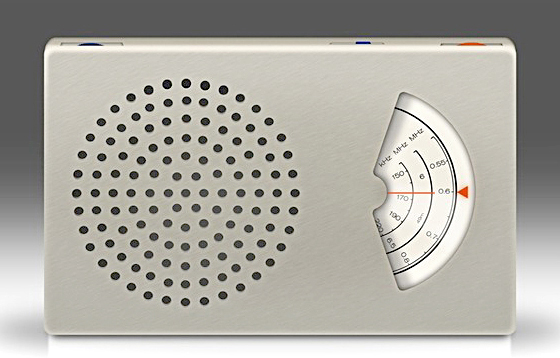

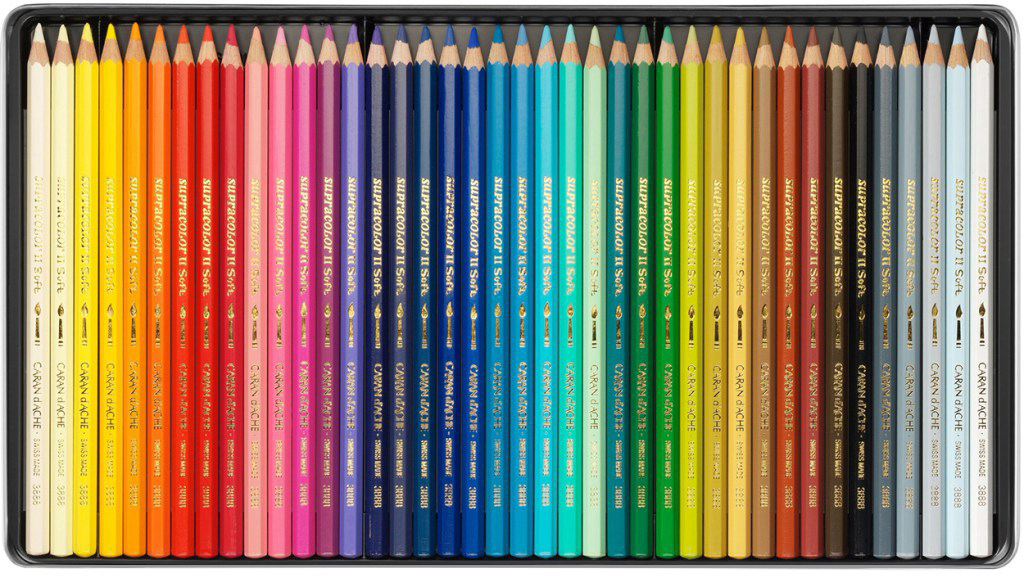

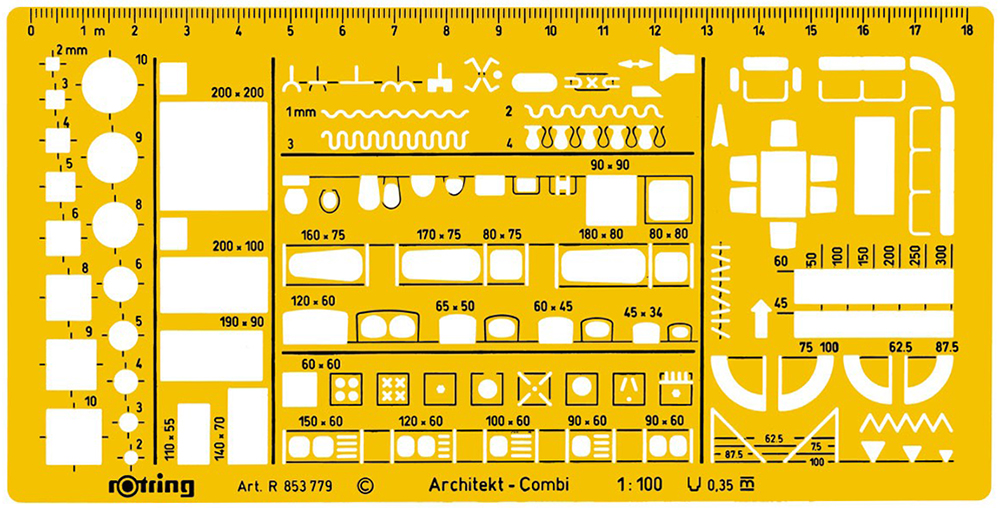

Years ago, before cellphones and computers, this was one of our pastimes. The current enthusiasm for adult coloring books seems to be closely related. Art made relatively easy using a simple system. It’s a low-stress activity with tangible results. Here are a couple of sets I purchased recently on eBay.

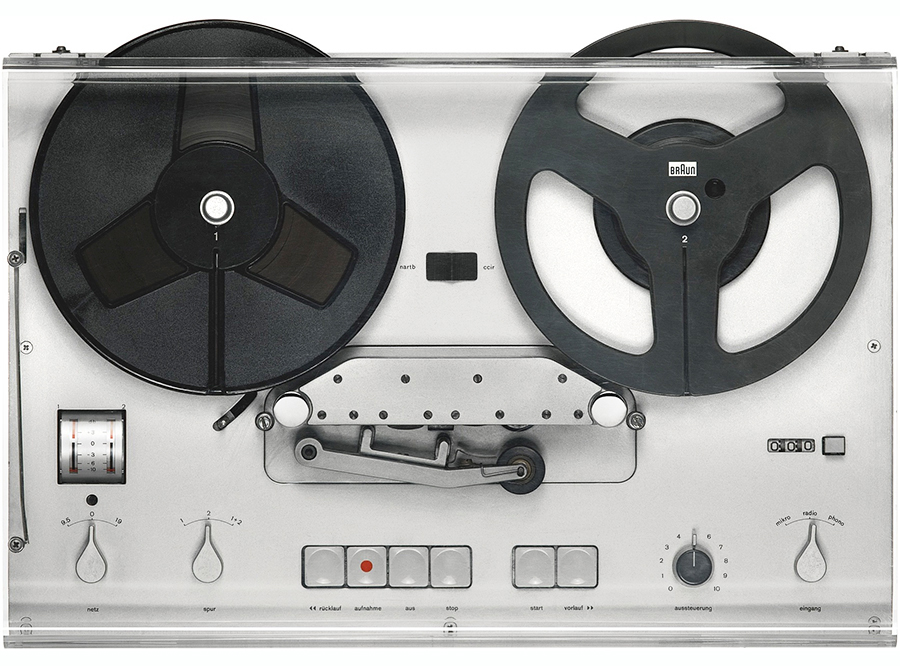

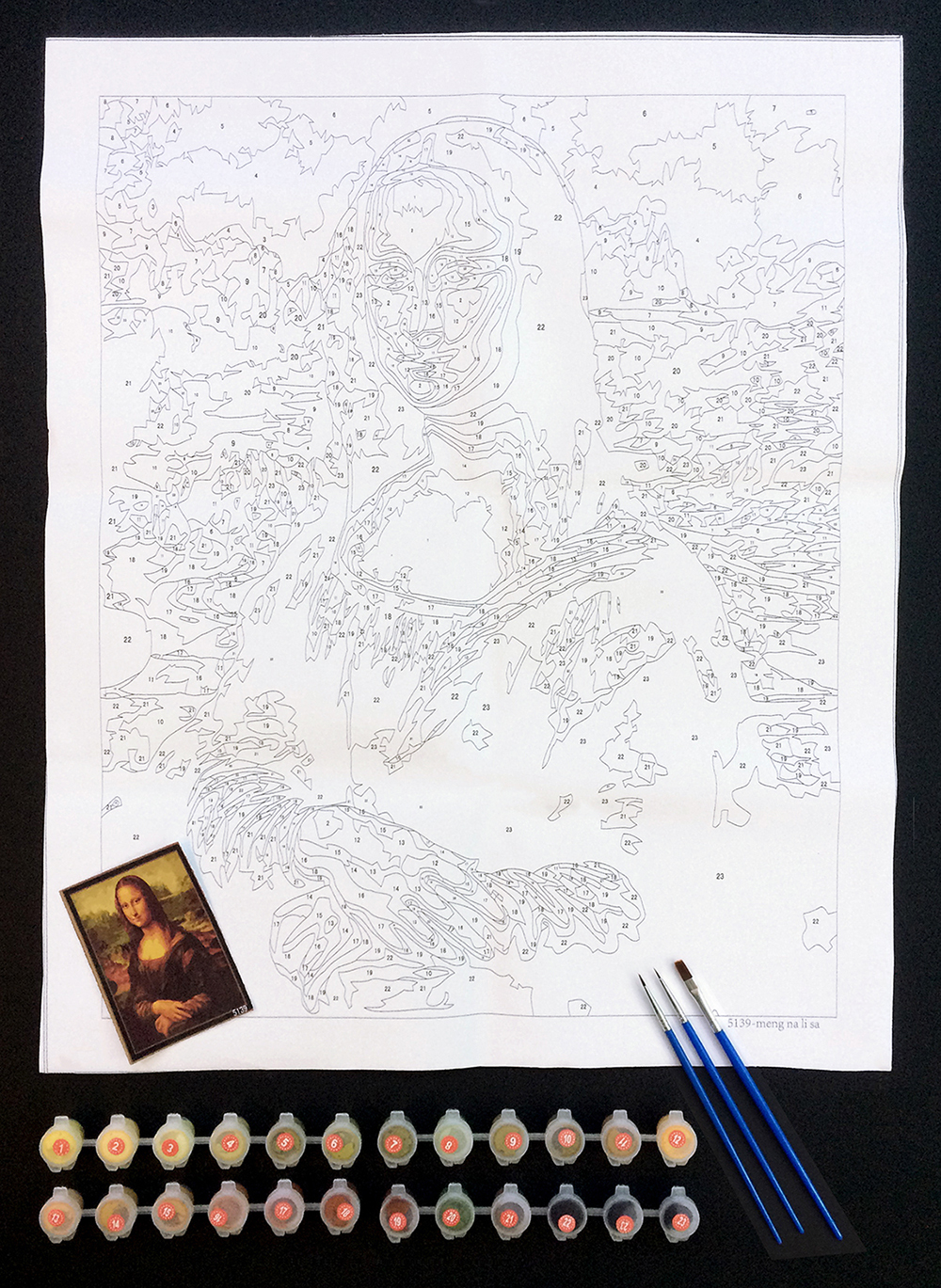

Mona Lisa (Shown above.) This one is on canvas for complete authenticity. Note the handy reference pic. Everything needed is here: A numbered keyline to follow, paintbrushes, and a set of acrylic paints with corresponding numbers. I need to start filling in the areas, but it looks quite challenging. The estimated value of the original painting is $1.5 billion. My Mona Lisa cost just $16.59 (with free shipping).

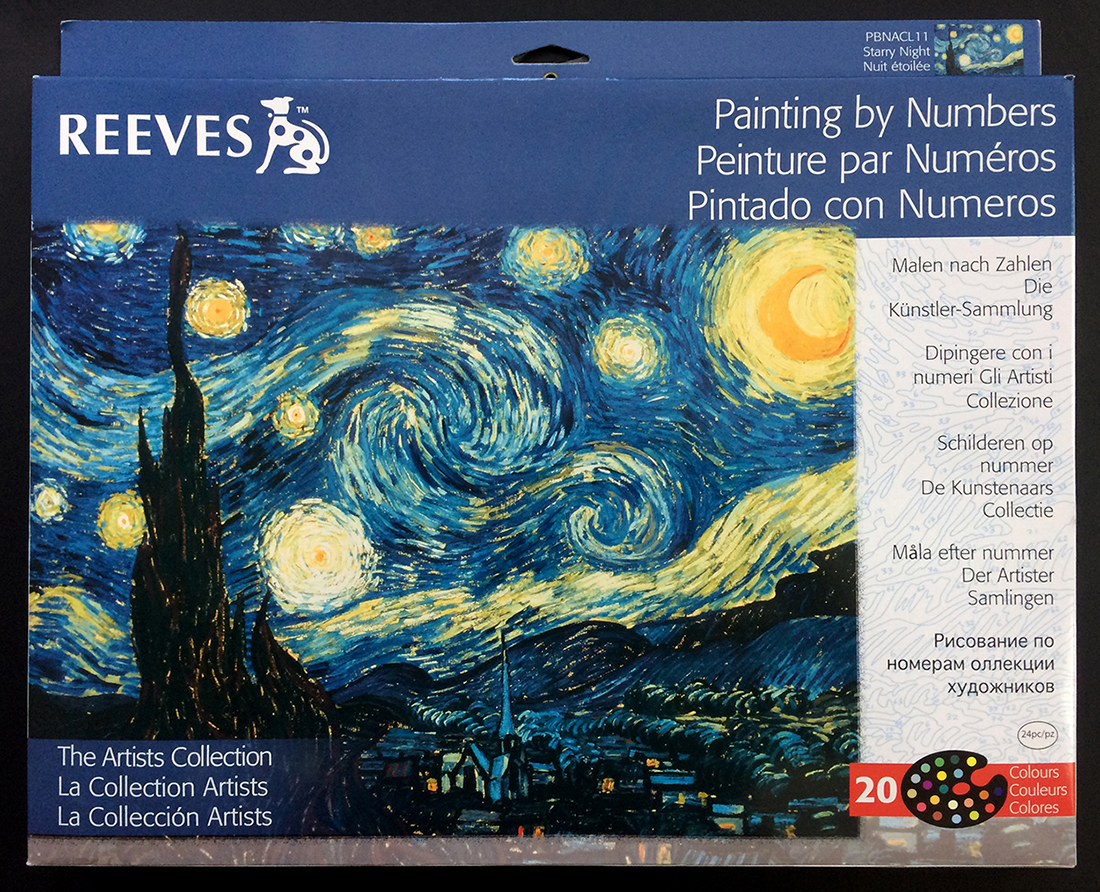

The Starry Night I’m going post-impressionist with this one.

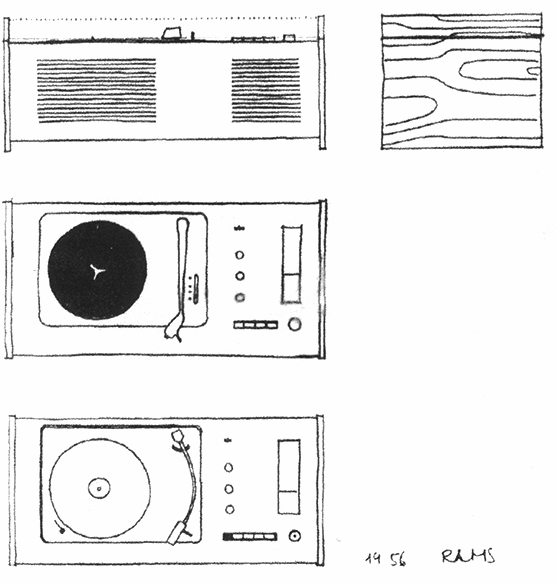

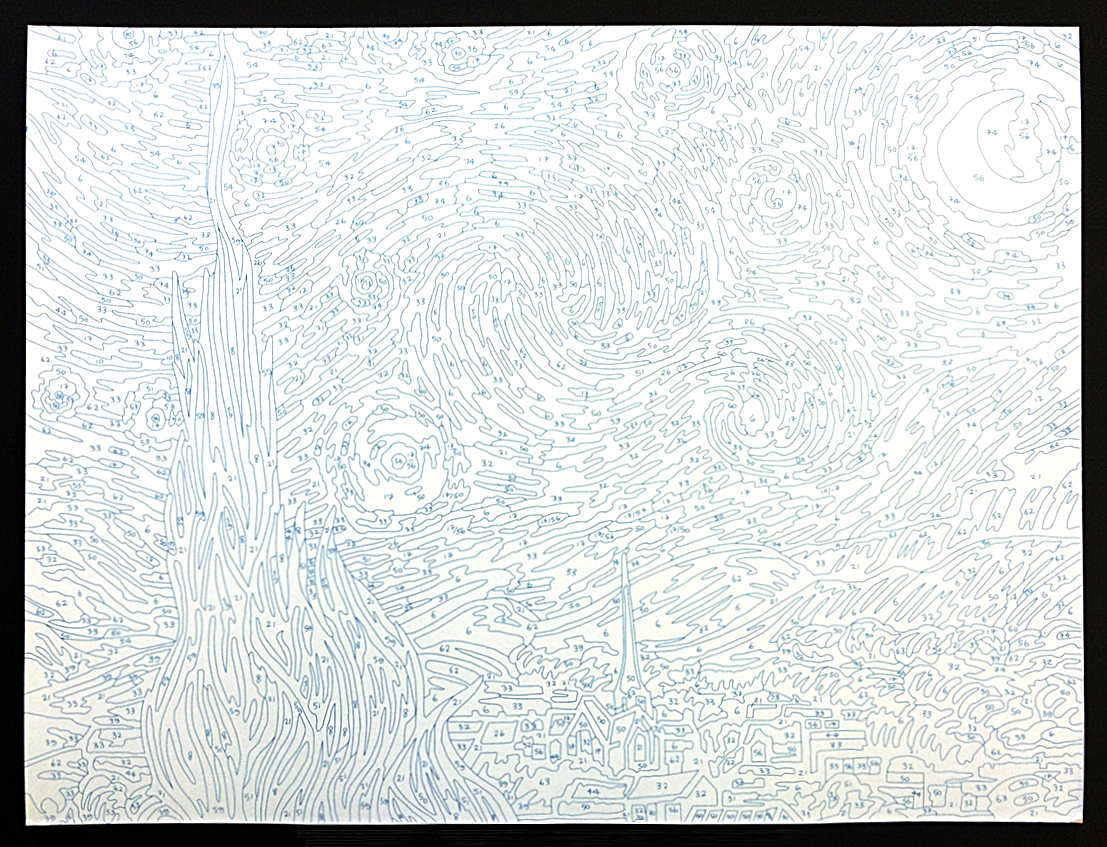

Lines on a board, ready to become art. Presumably, this is not how Van Gogh planned the painting.

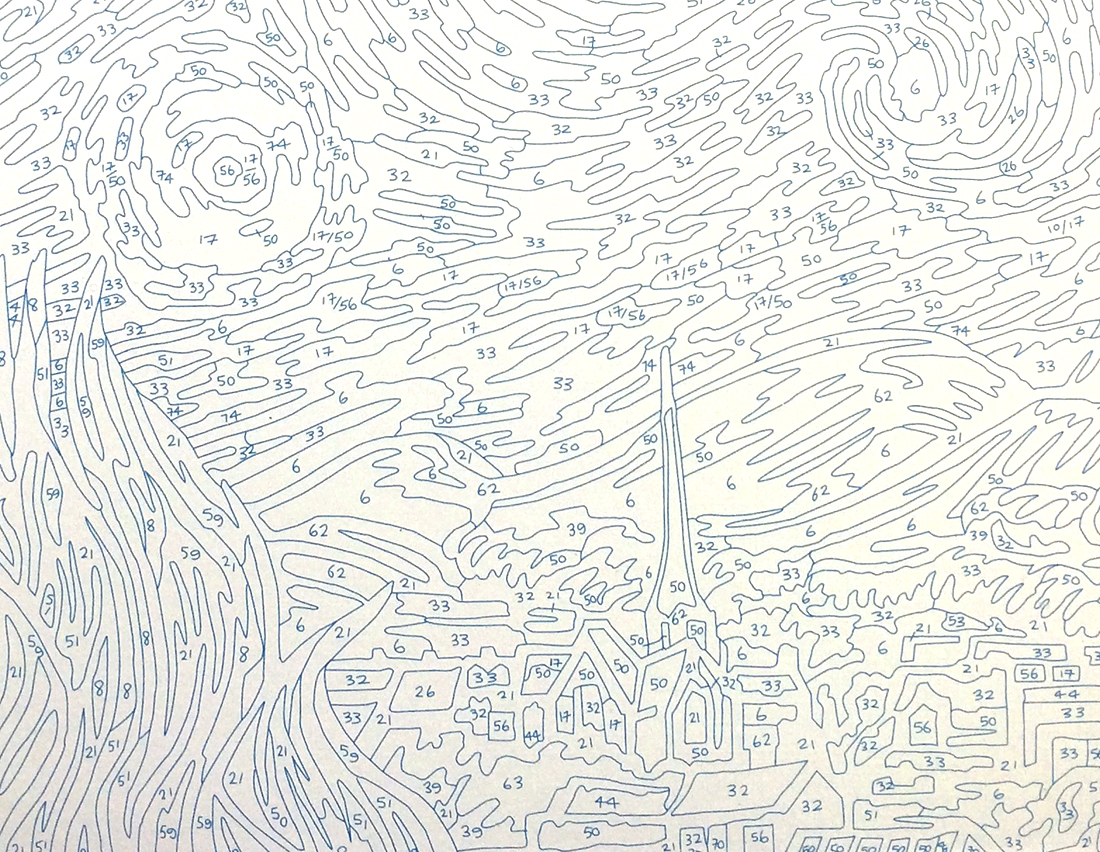

A detail. For areas with two numbers, the colors have to be mixed together. Fortunately, blending between the color areas is not suggested. Some sets that I had years ago (with oil-based paints) offered that additional task. The edges that were to get a smooth transition were indicated by dashed lines.

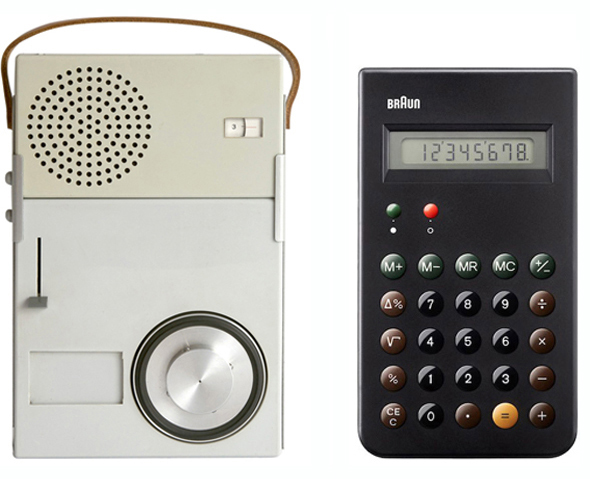

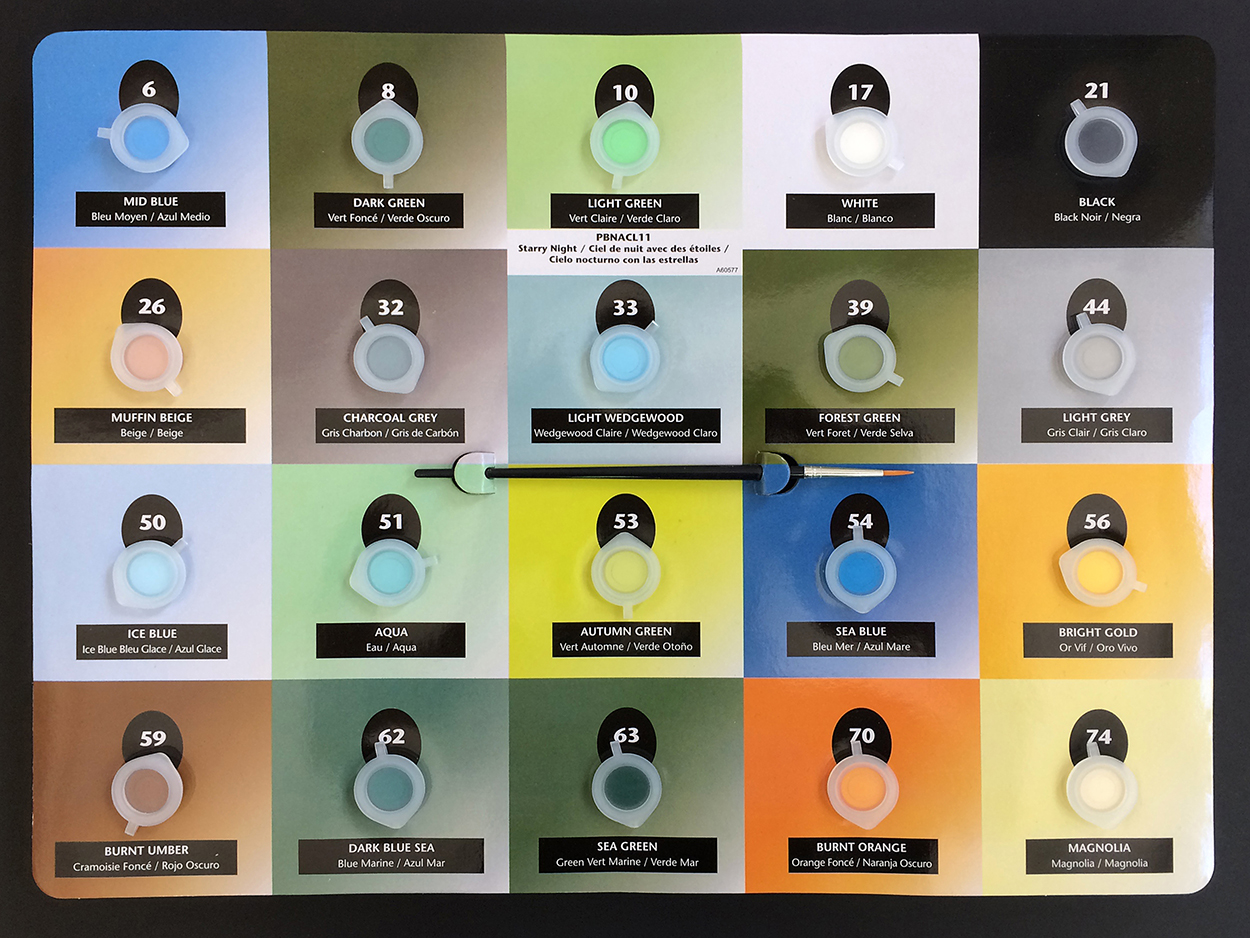

The required paints. Reeves has a numbered system that works across all their painting by numbers sets. No number one (lemon yellow) here.

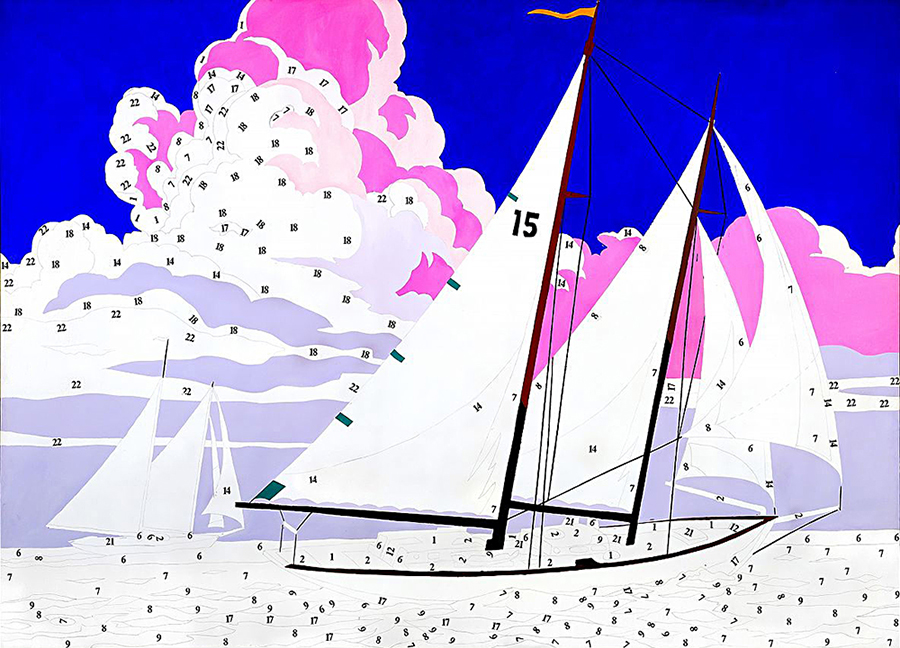

In the gallery Andy Warhol’s 1962 “Do It Yourself” series is a tribute to the “painting by numbers” craze.

COMING NEXT WEEK: Two posts about In Graphics, a brilliant magazine where all the pages are infographics. Below, staff at Infographics Group in Berlin review proofs of the new issue (number ten).