THE MICRO WORLD.

![]()

![]()

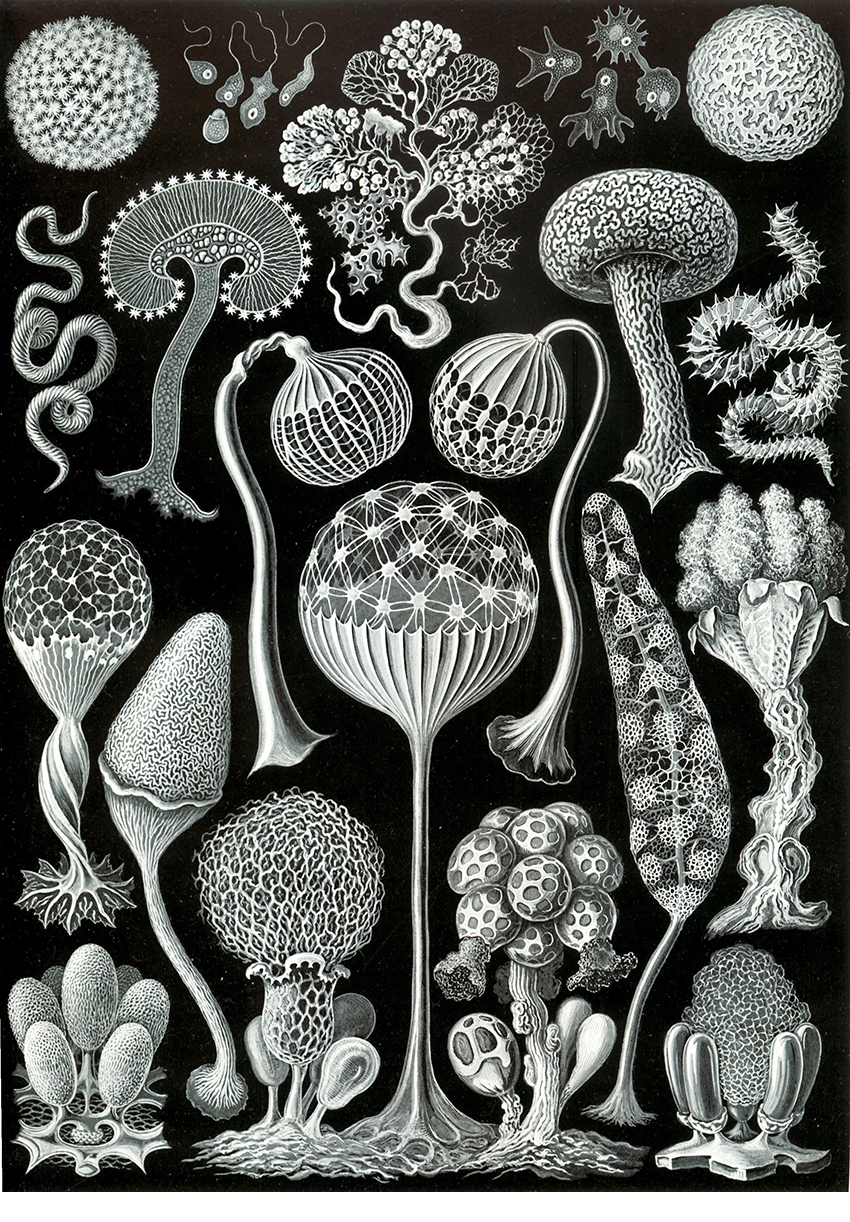

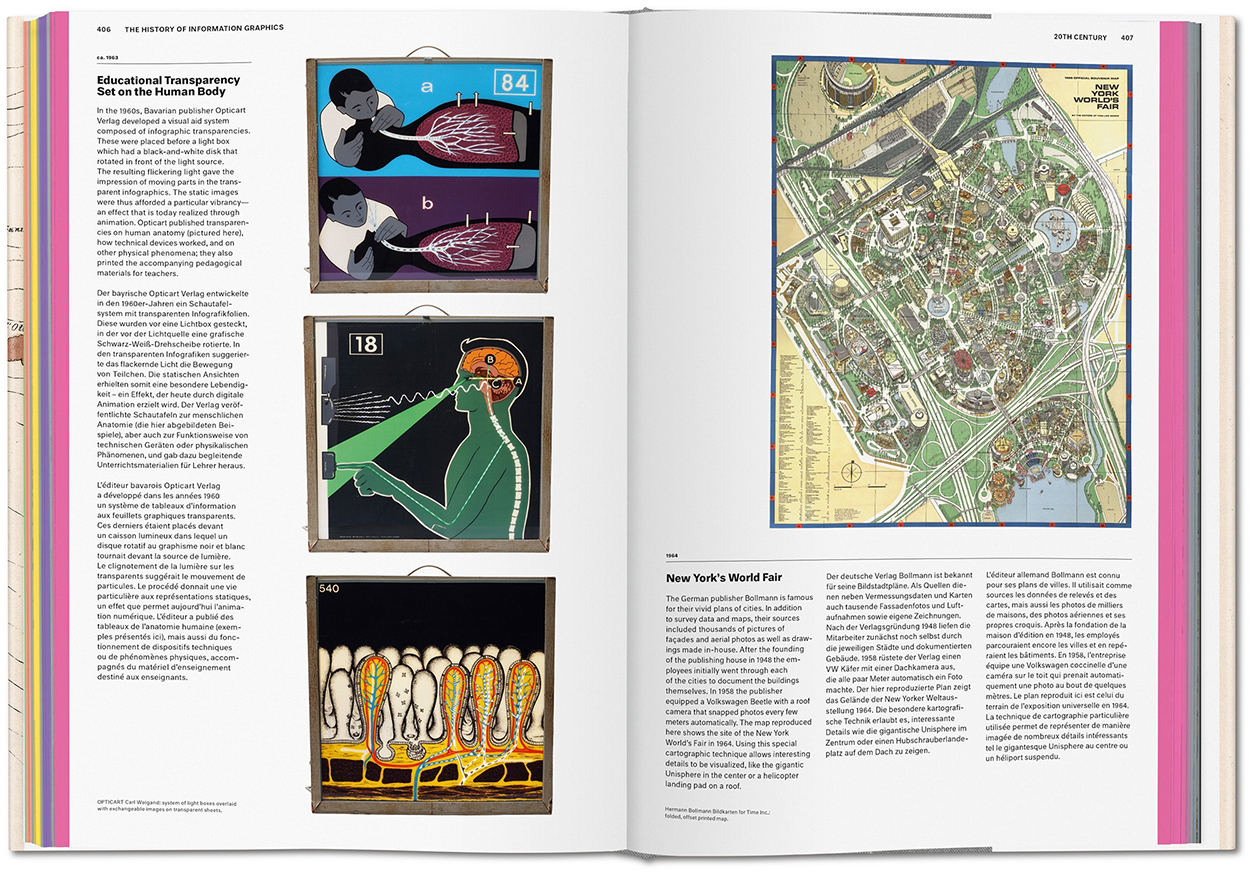

Micrographs

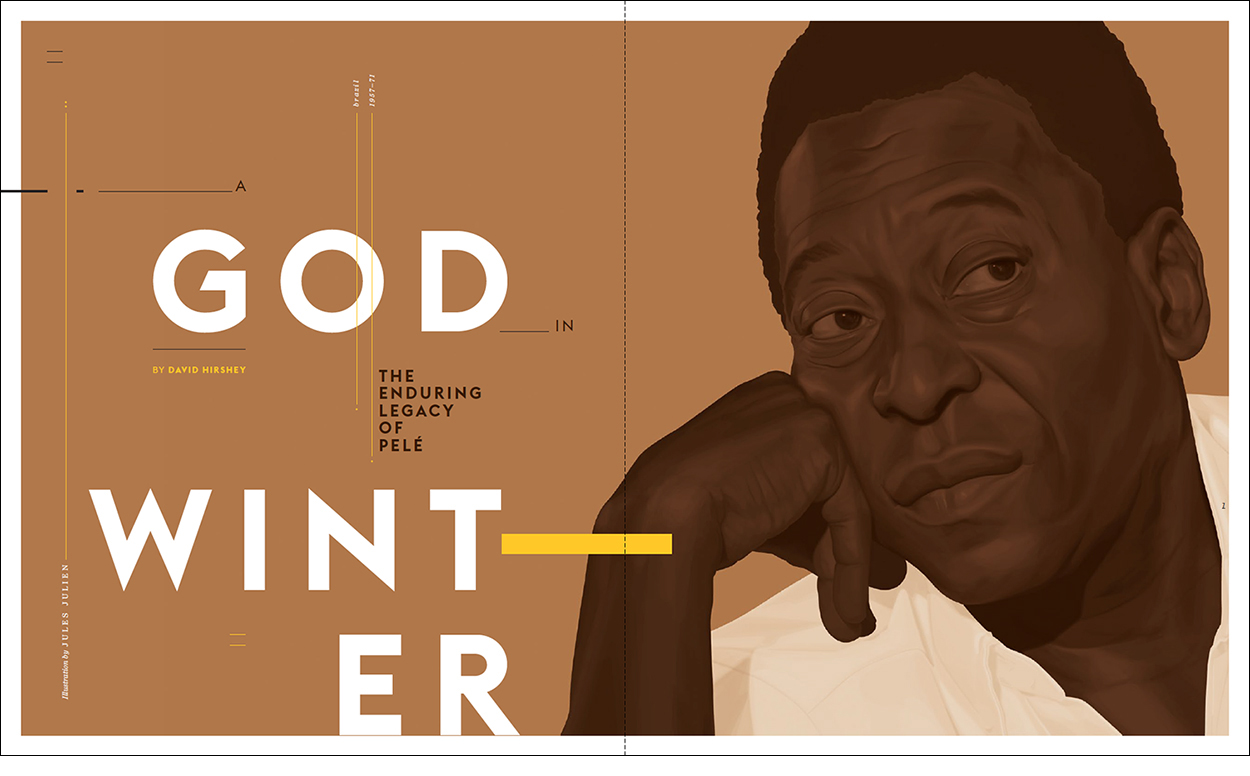

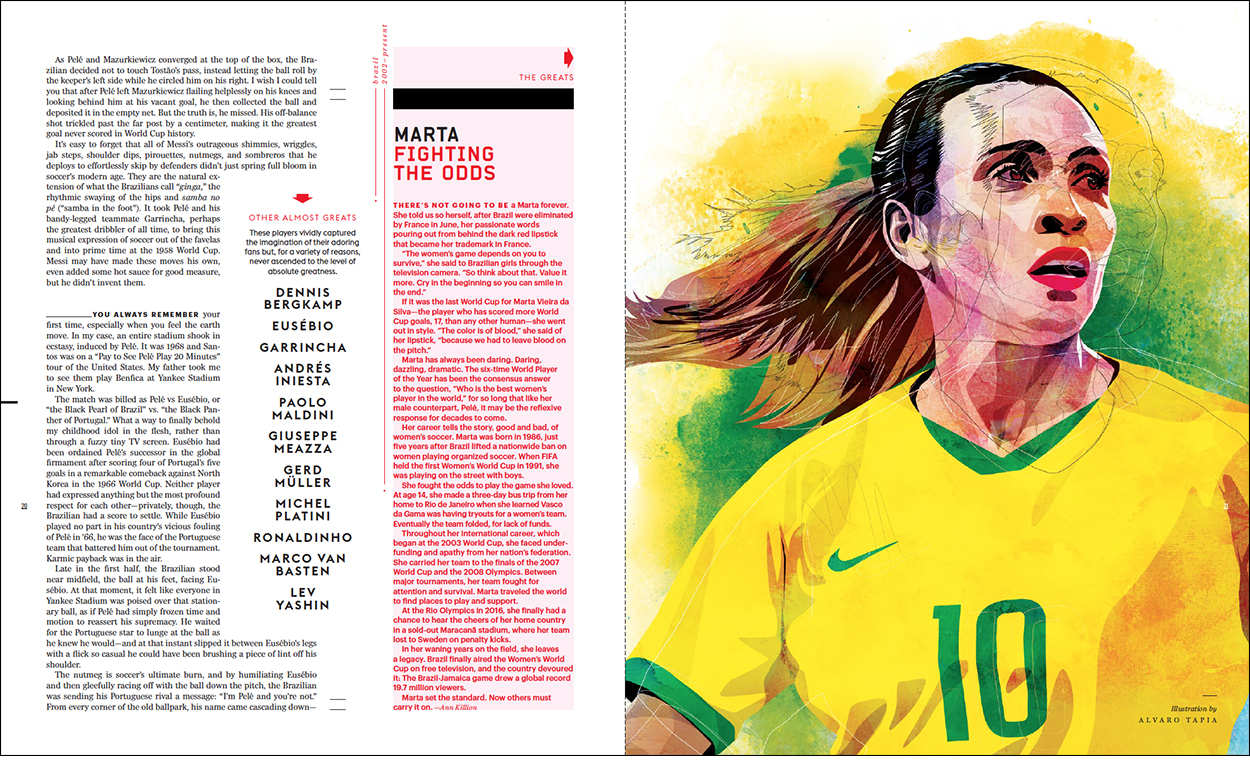

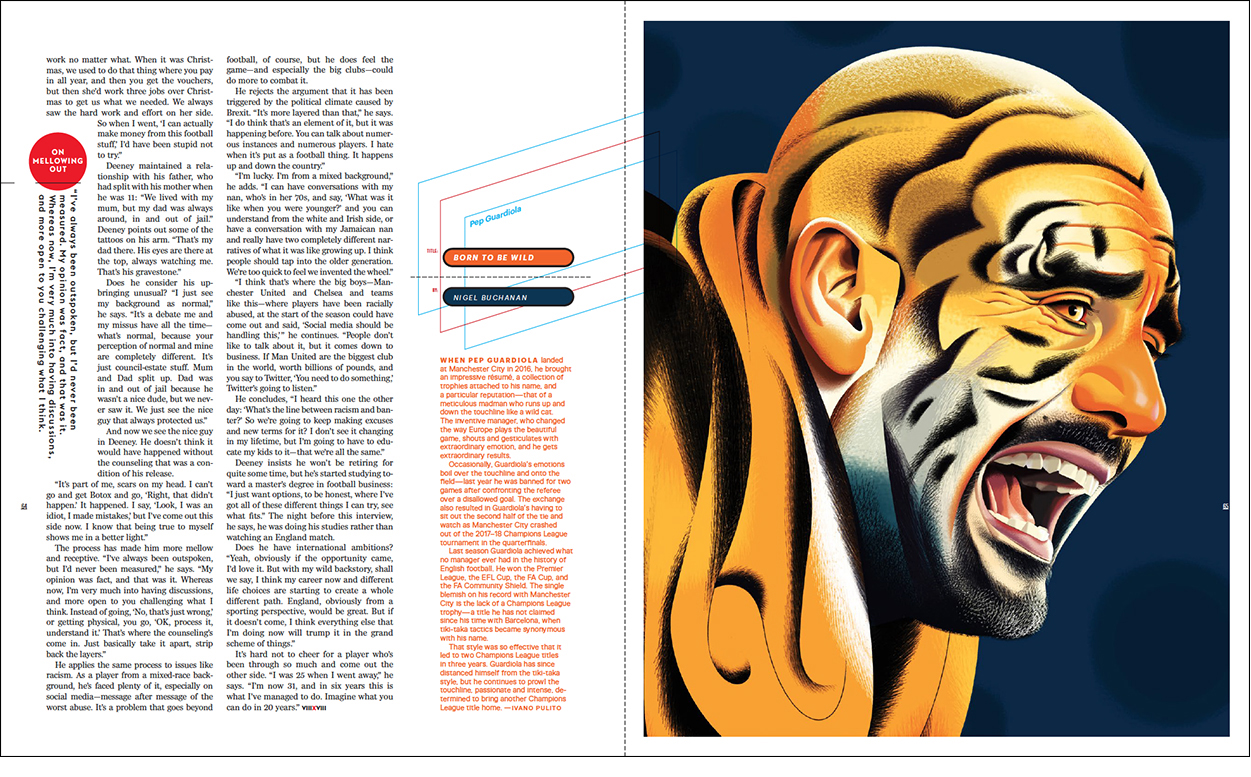

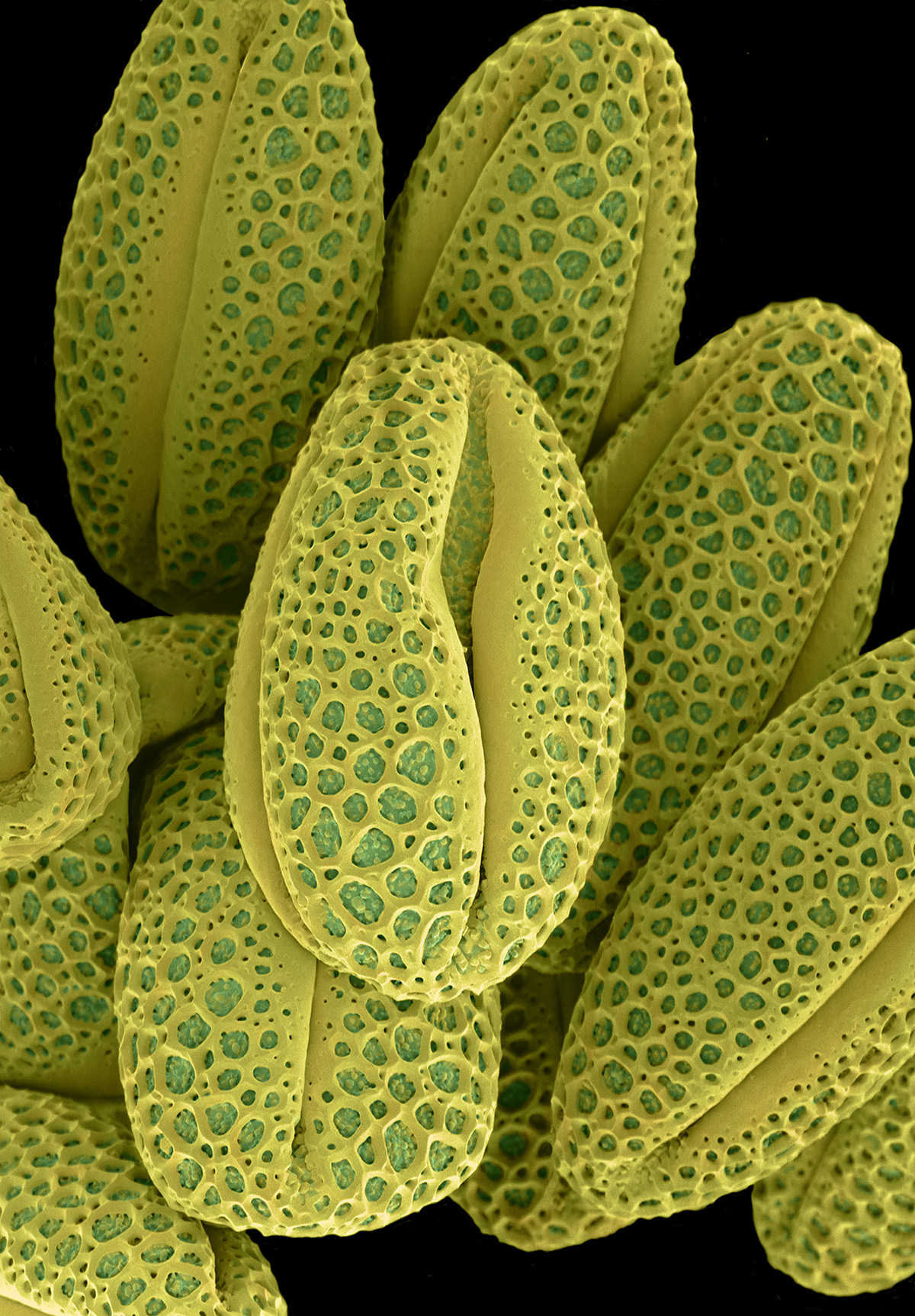

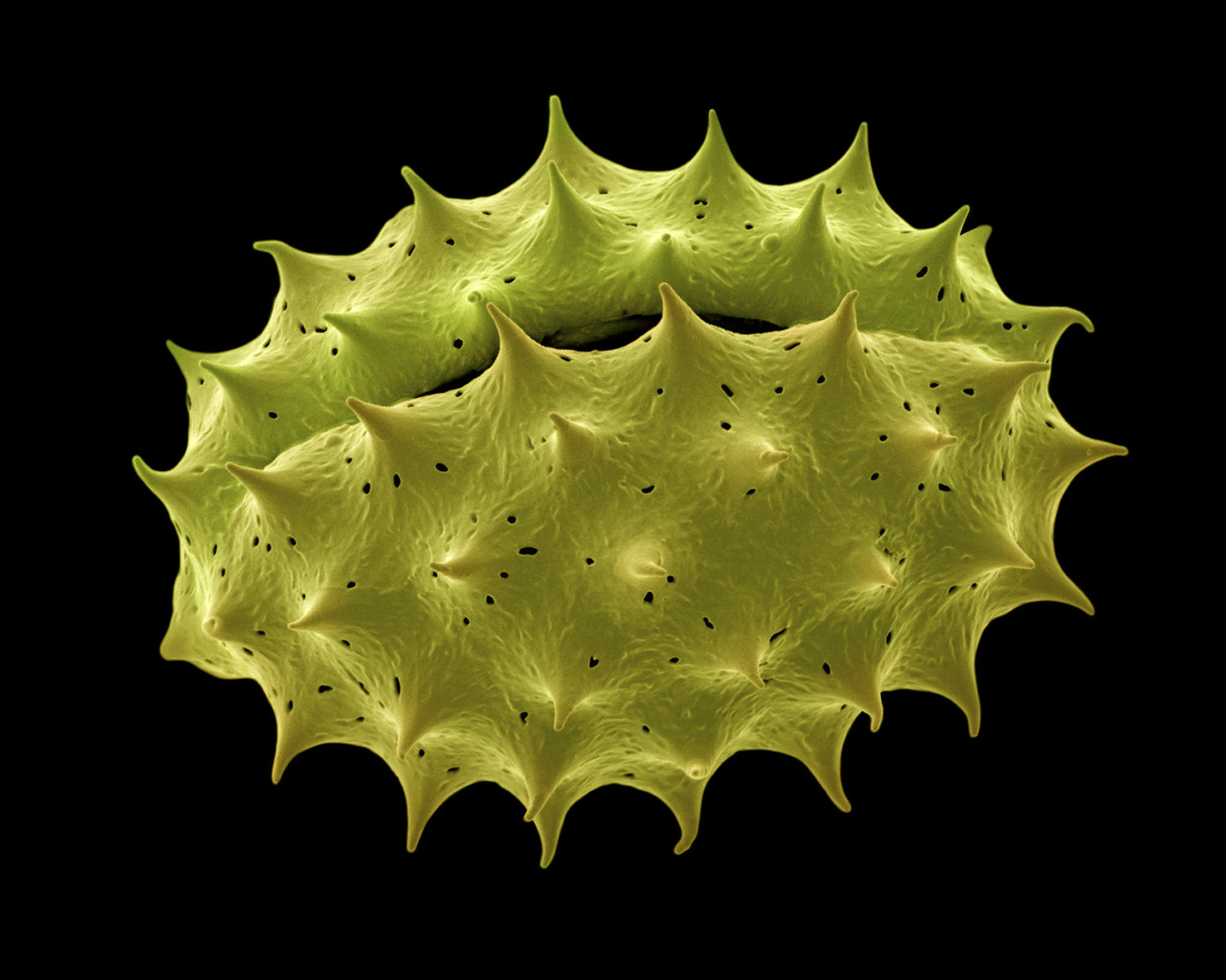

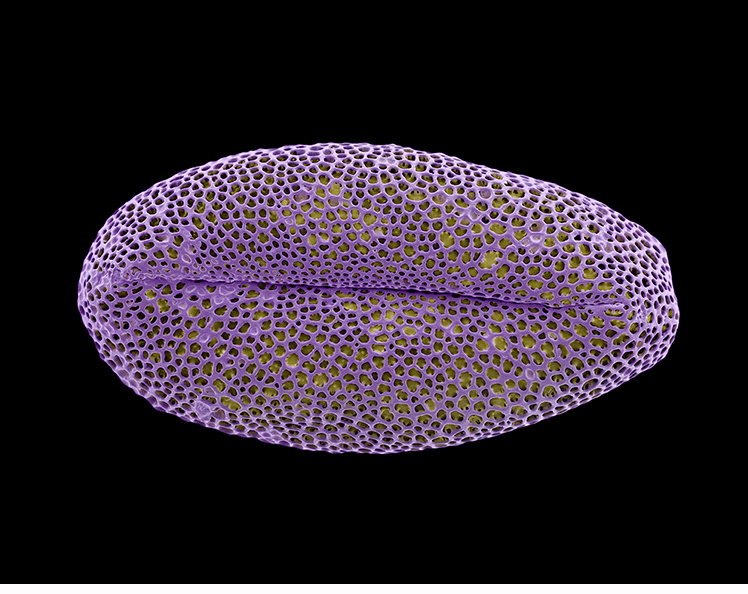

Rob Kesseler reveals the unseen world of plants in the “PHY-TOPIC” series. Using a range of complex microscopy processes, he creates composite images, adding many subtle layers of color that reveal functional and structural characteristics. Rob’s work combines science and art in the tradition of visual scientific discovery that goes back centuries. He is a Professor of Arts, Design & Science at Central Saint Martins, London. See more work here: http://www.robkesseler.co.uk

Above, Daucus carota. Wild carrot. Fruit. (From “Fruit, Edible, Inedible, Incredible” by Rob Kesseler and Wolfgang Stuppy. Published by Papadakis.) https://bit.ly/2SW7aYS

Medicago arborea. Tree medick seedpod.

Salix caprea. Goat willow, collection of pollen grains.

Santolina chamaecyparissus. Cotton lavender, pollen grain.

Stellaria media. Chickweed, pollen grain on anther.

Viburnum. Stellate leaf hairs.

Westringia. Coastal rosemary, pollen grain.

All images © Rob Kesseler

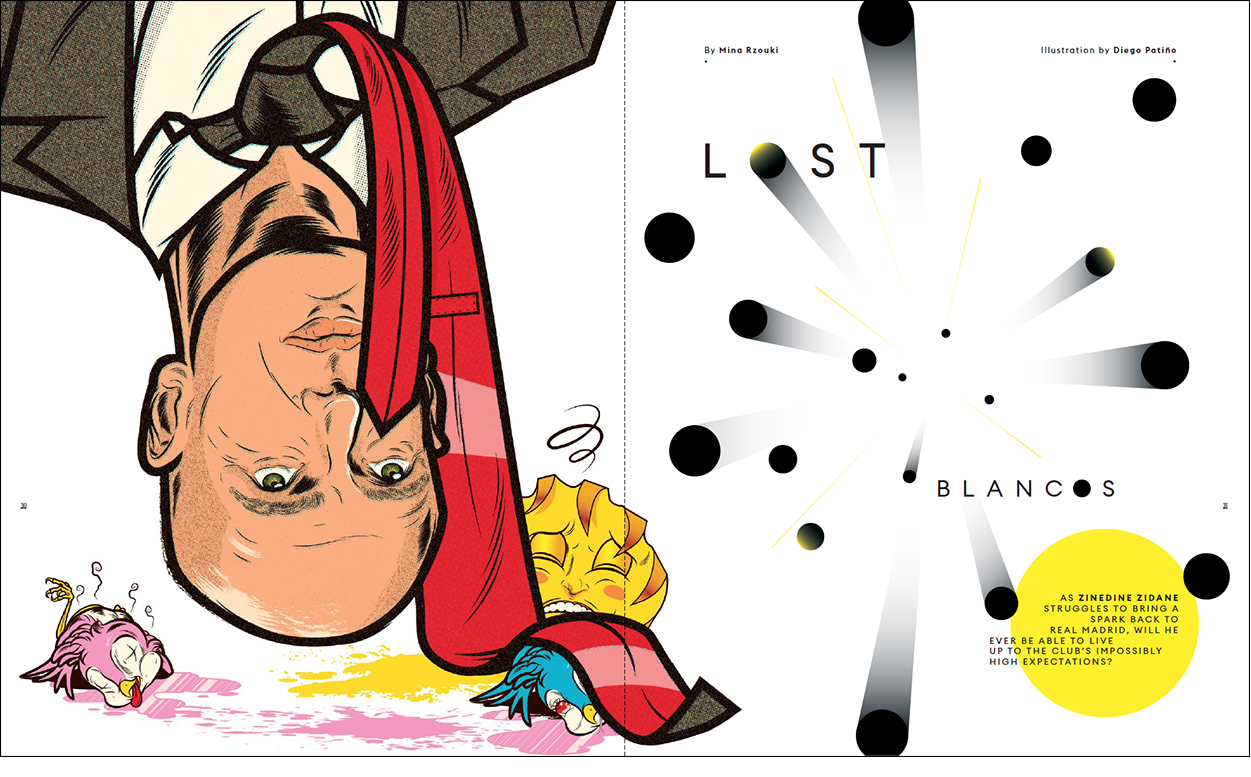

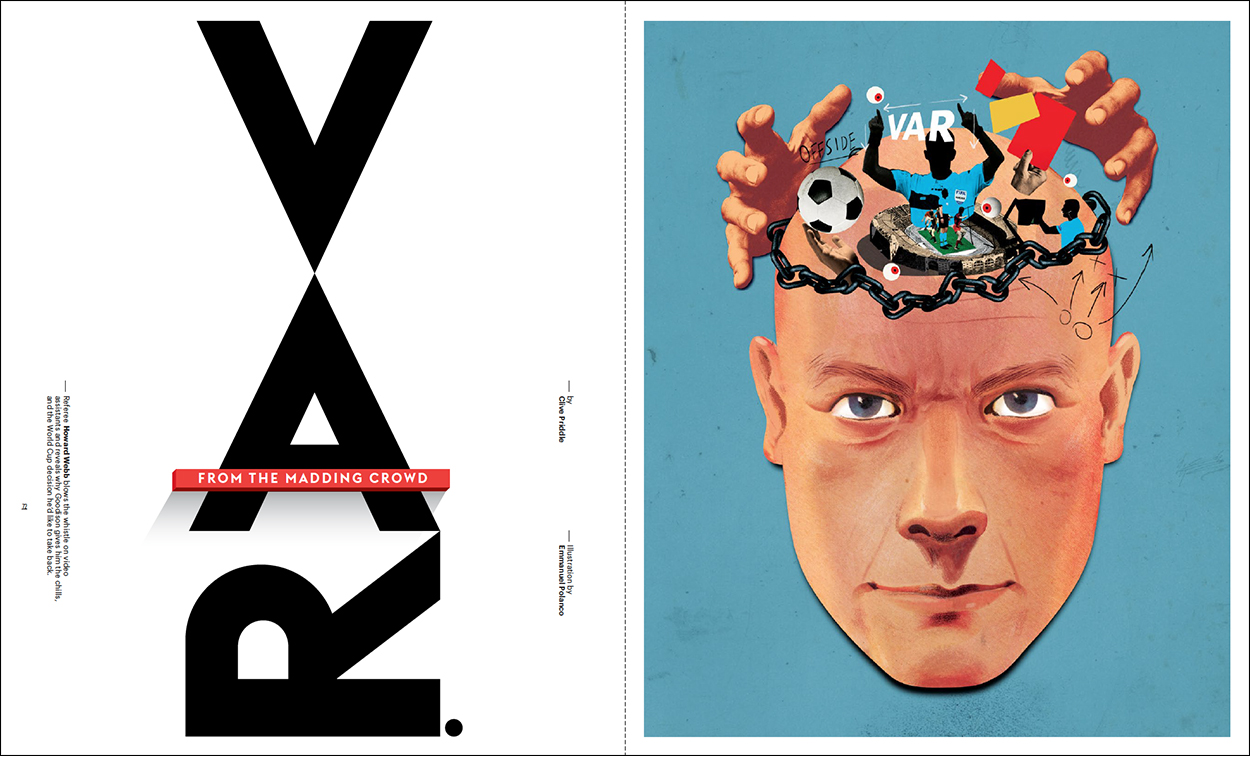

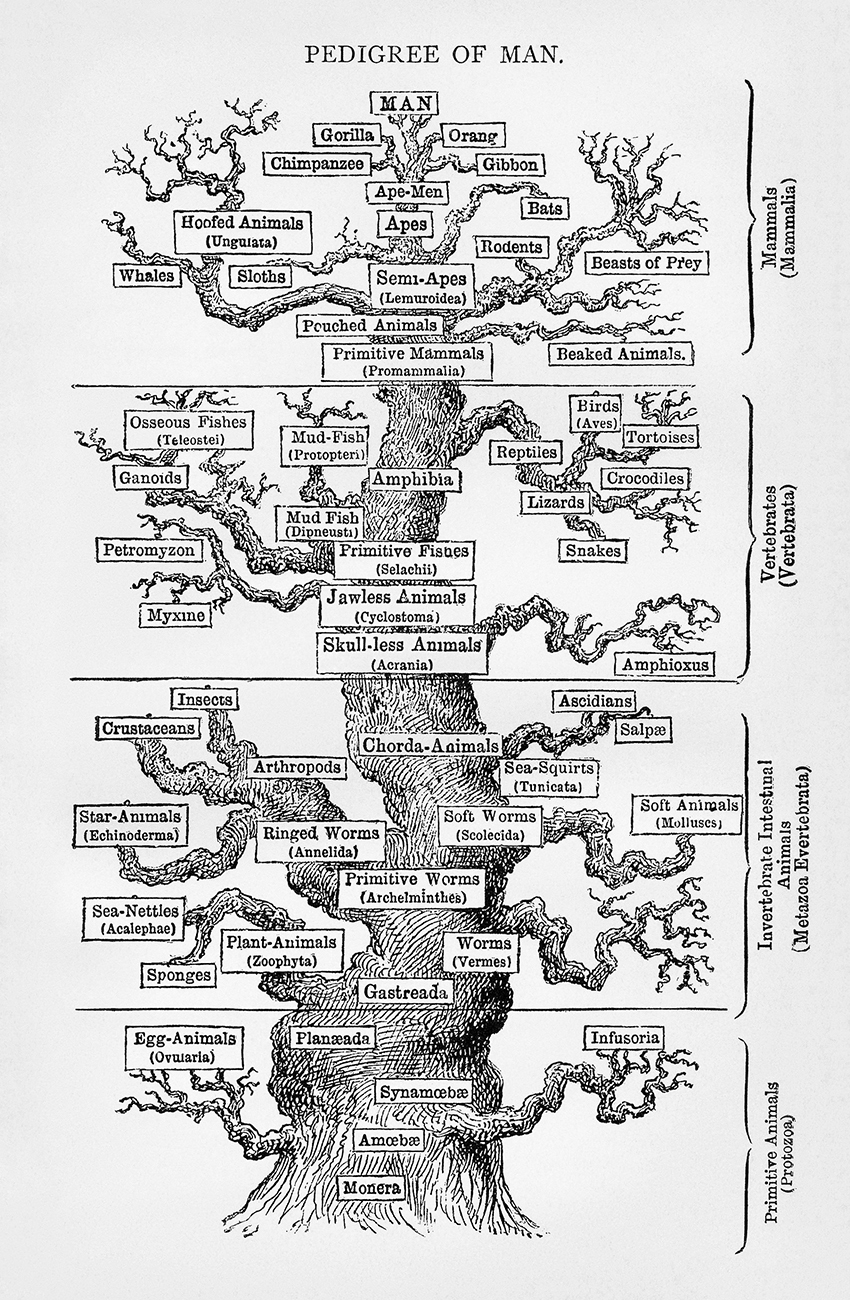

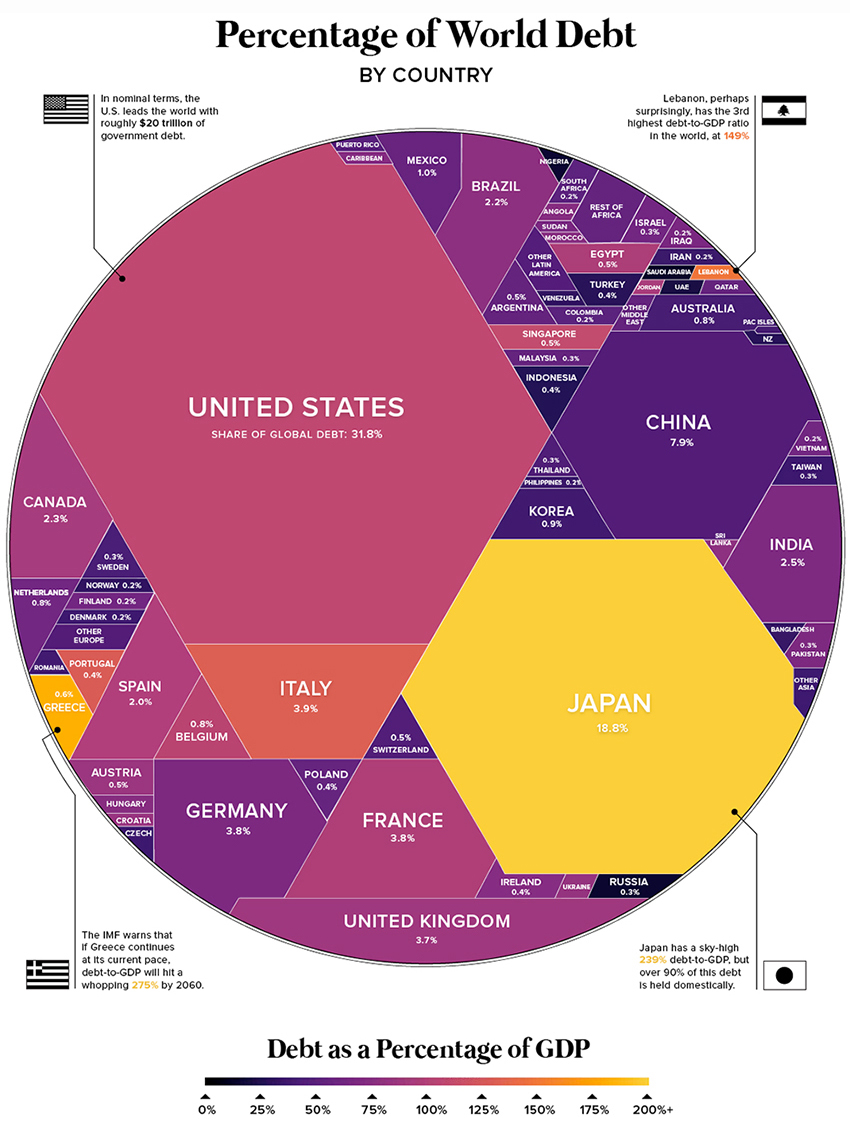

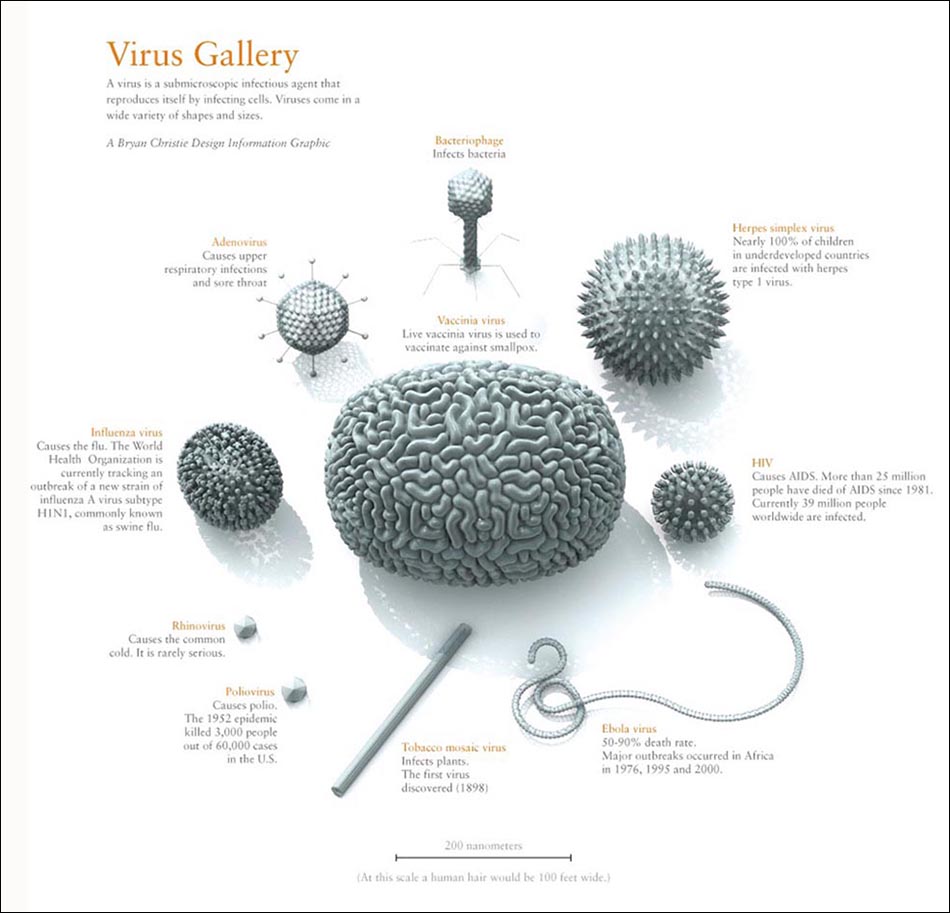

Recognizing viruses

Unseen invaders, by Bryan Christie Design. This illustration is from 2009, which explains the influenza virus being swine flu. Today that would, of course, be COVID-19, which has turned our world upside down.

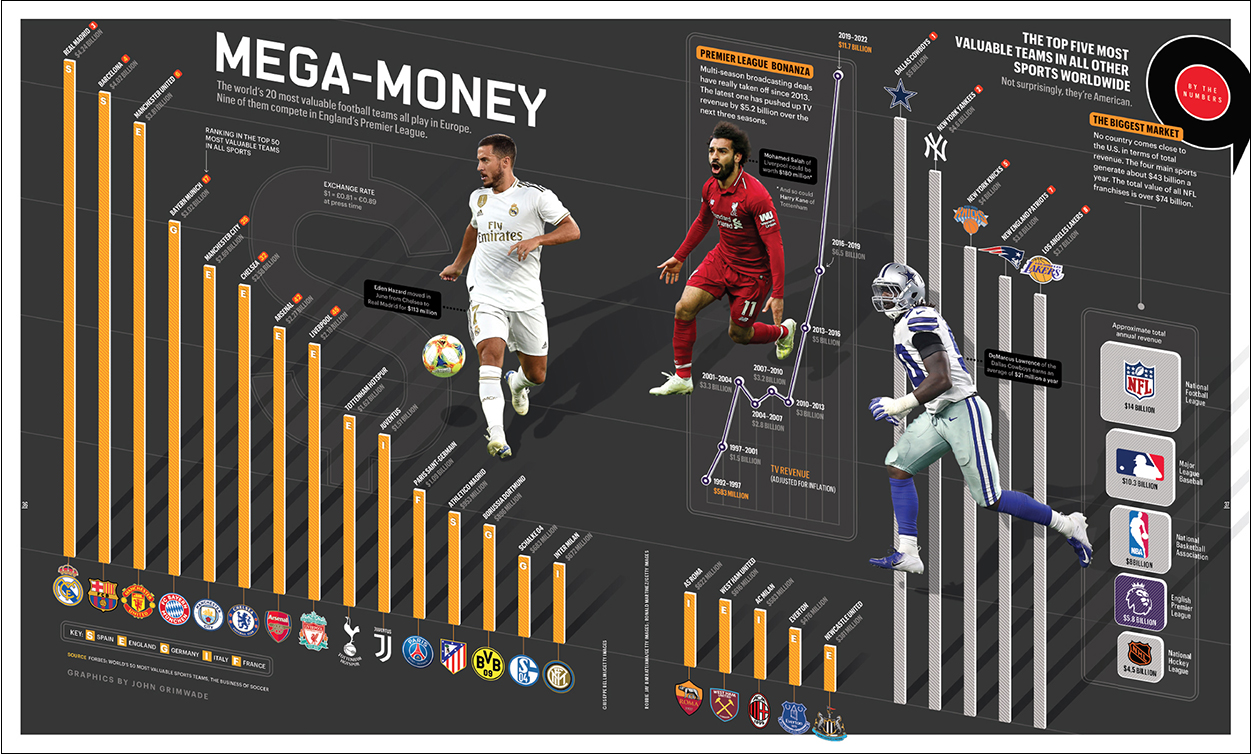

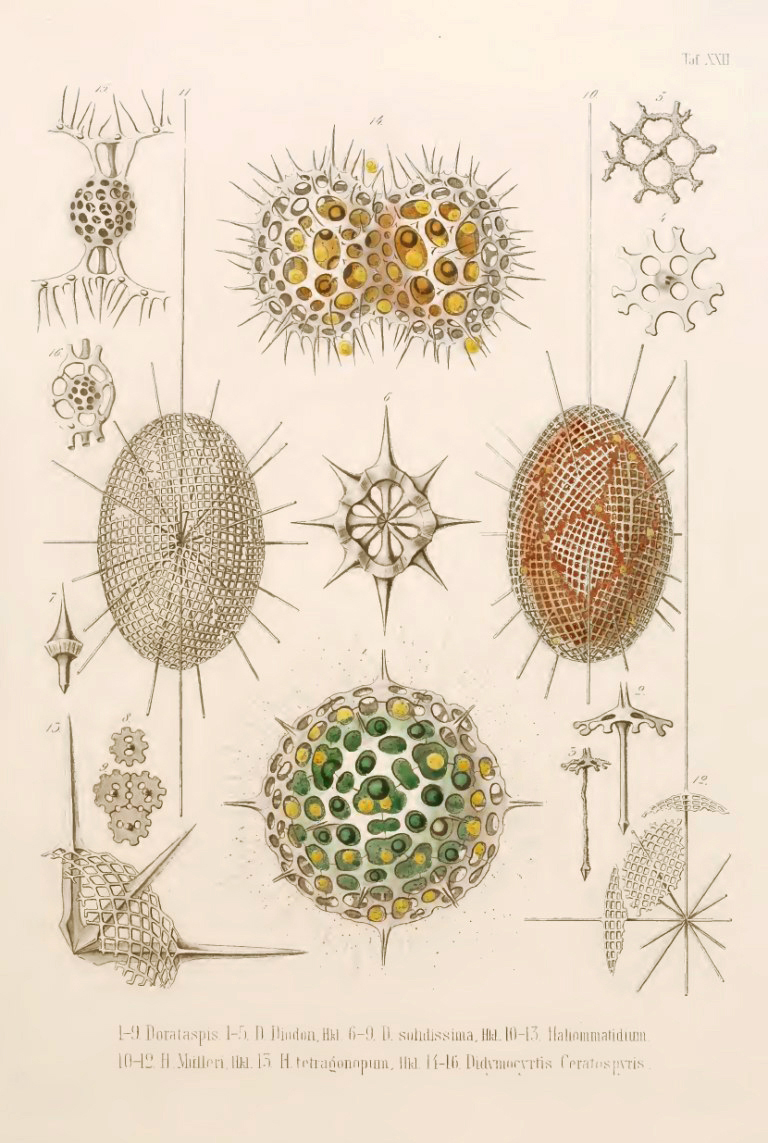

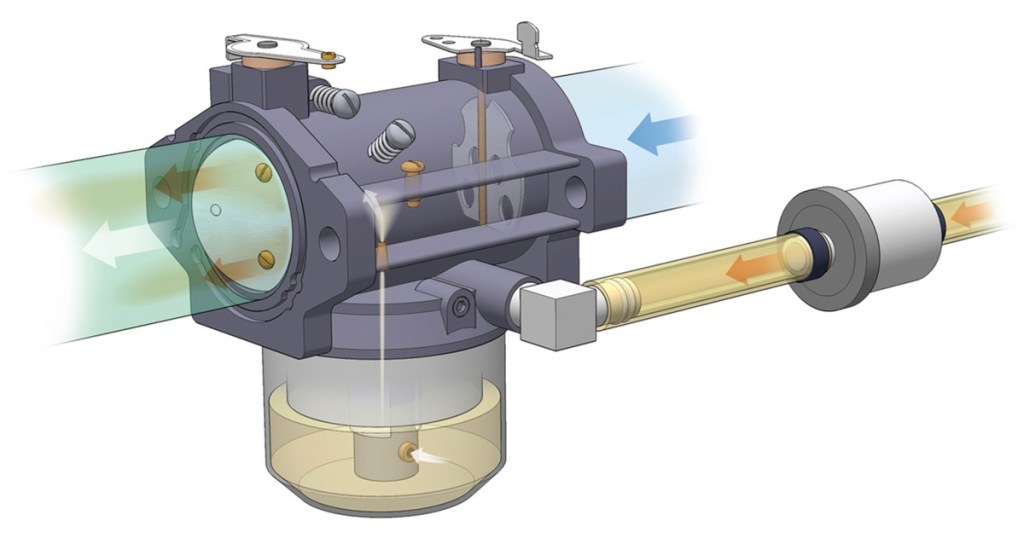

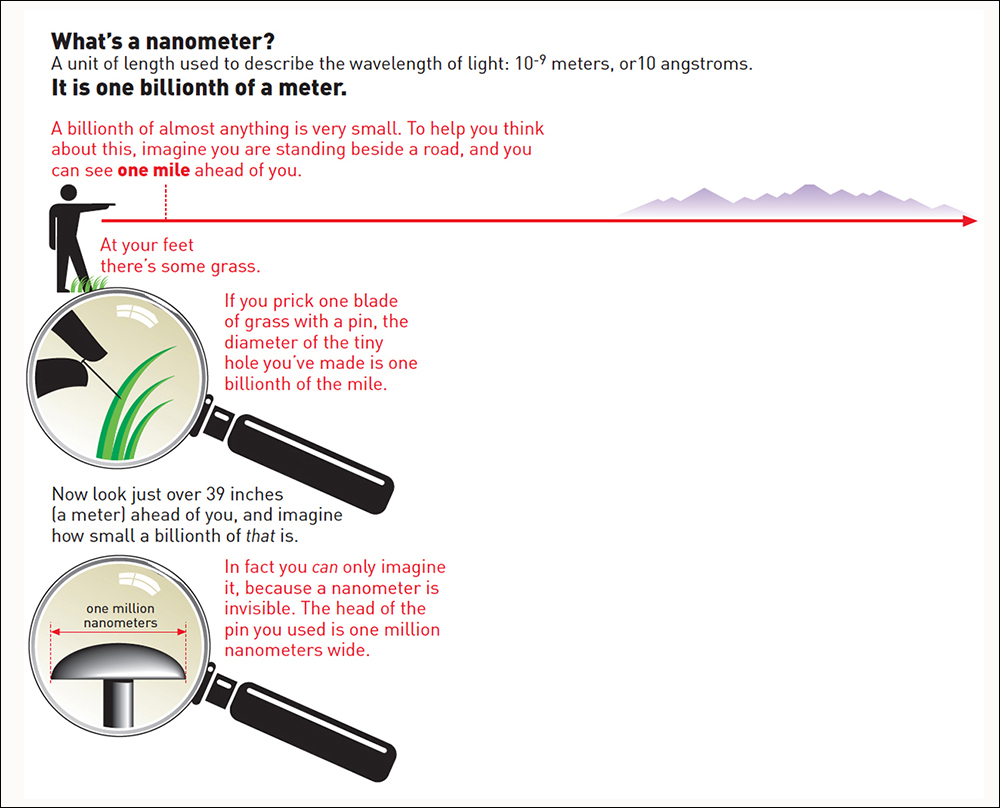

Nanometer

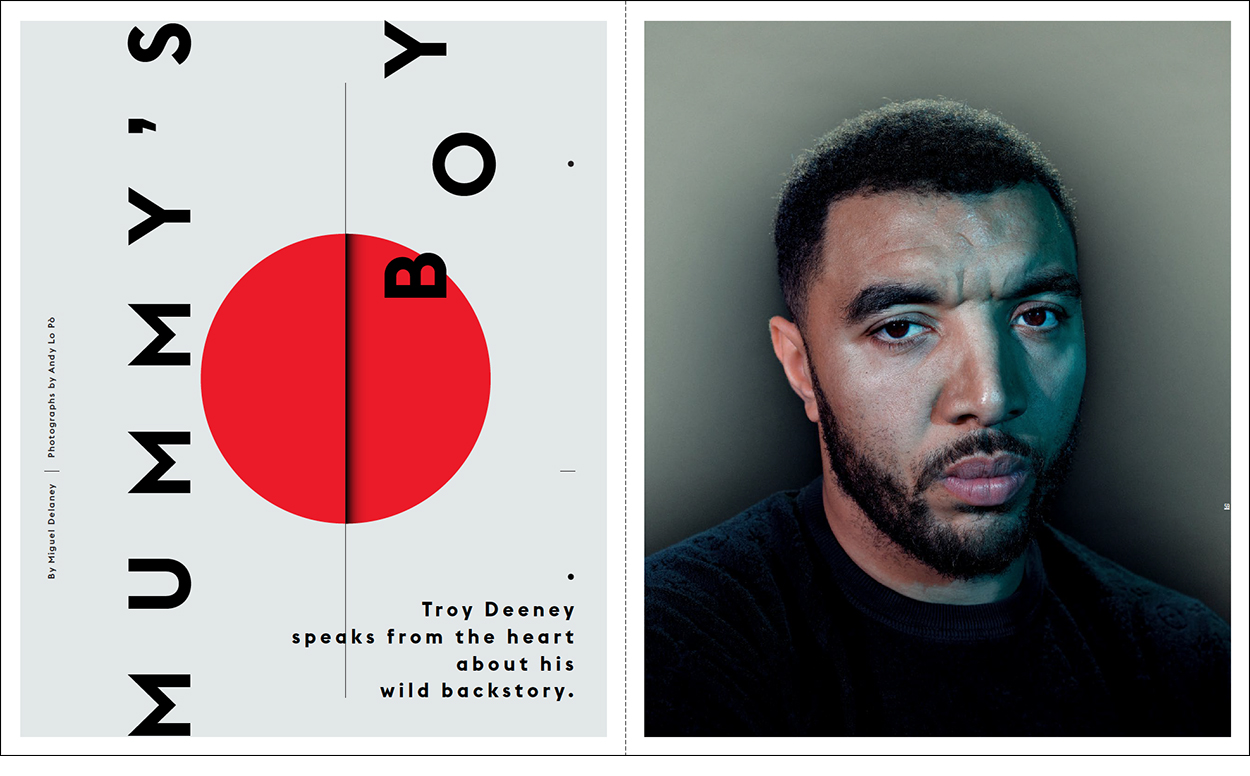

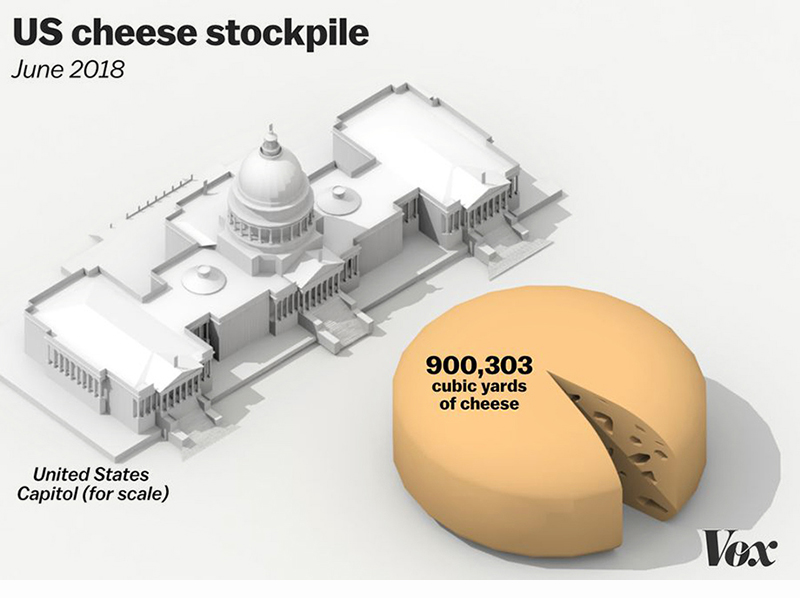

Nigel Holmes explains a measurement that’s used for very small items. An example: DNA is about two nanometers in diameter.

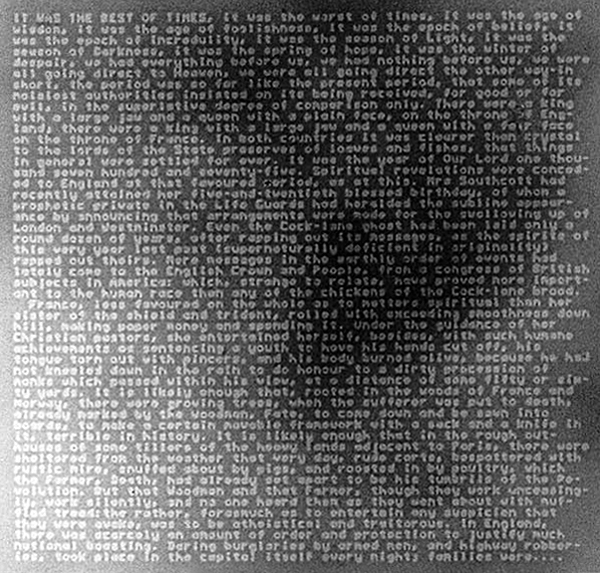

The head of a pin

In 1959, physicist Richard Feynman challenged scientists to find a way to inscribe a book page 25,000 times smaller than in it’s regular printed form. 25 years later, Tom Newman used a beam of electrons to etch the first page of Charles Dickens’“A Tale of Two Cities” on a piece of plastic 200 microns* square. At this scale, the entire Encyclopedia Britannica would fit on the head of a pin (which was the original challenge).

* 1 micron = 1,000 nanometers.

Someone once told me that my knowledge of mathematics could be written on the head of a pin with a sledgehammer. I made a few bad numerical errors in infographics earlier in my career, so that statement was not entirely off the mark.

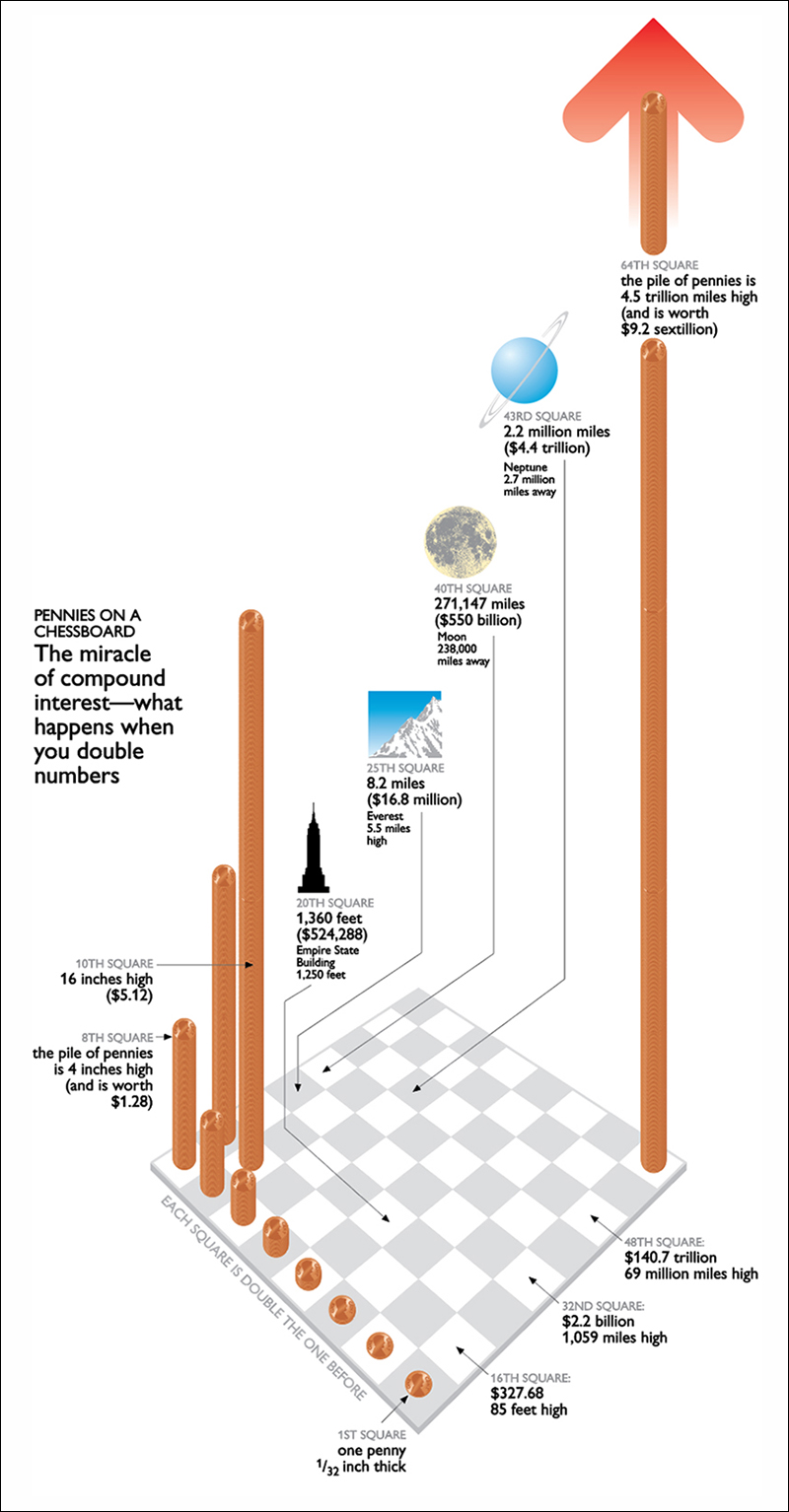

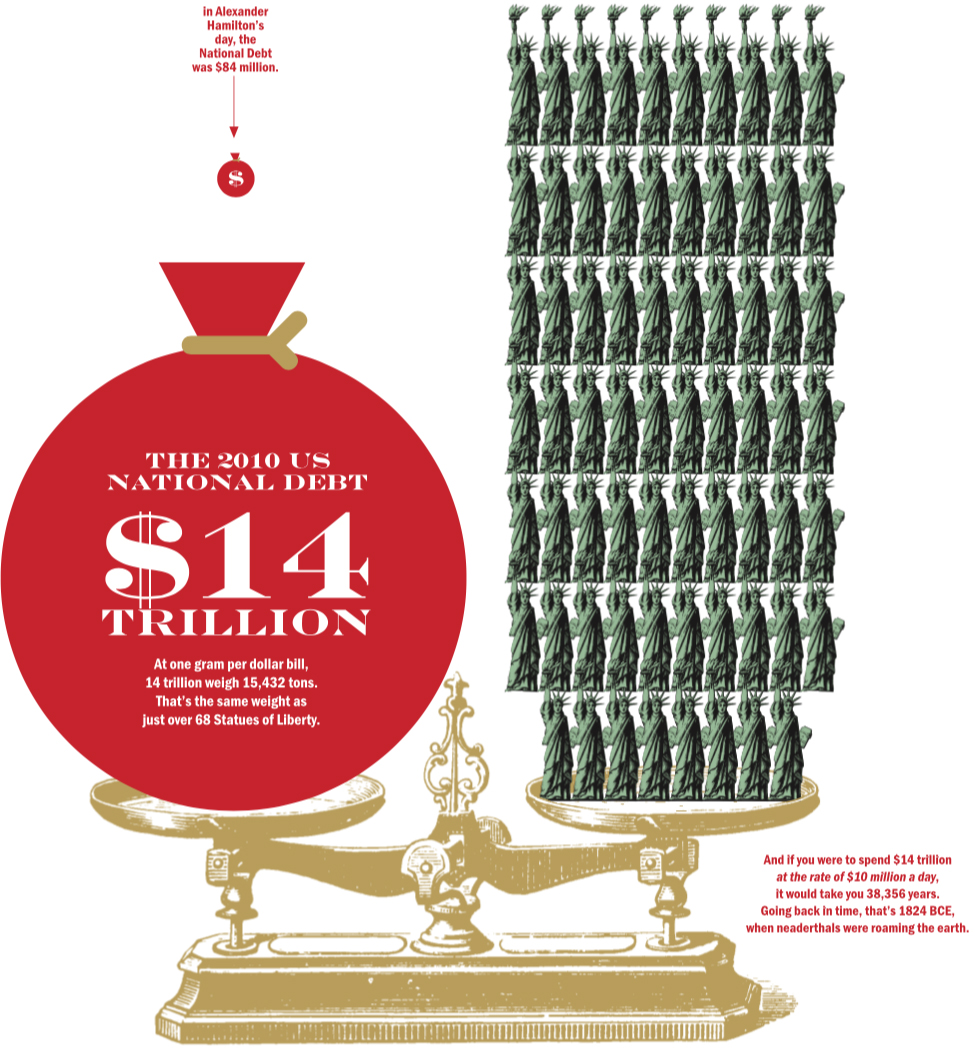

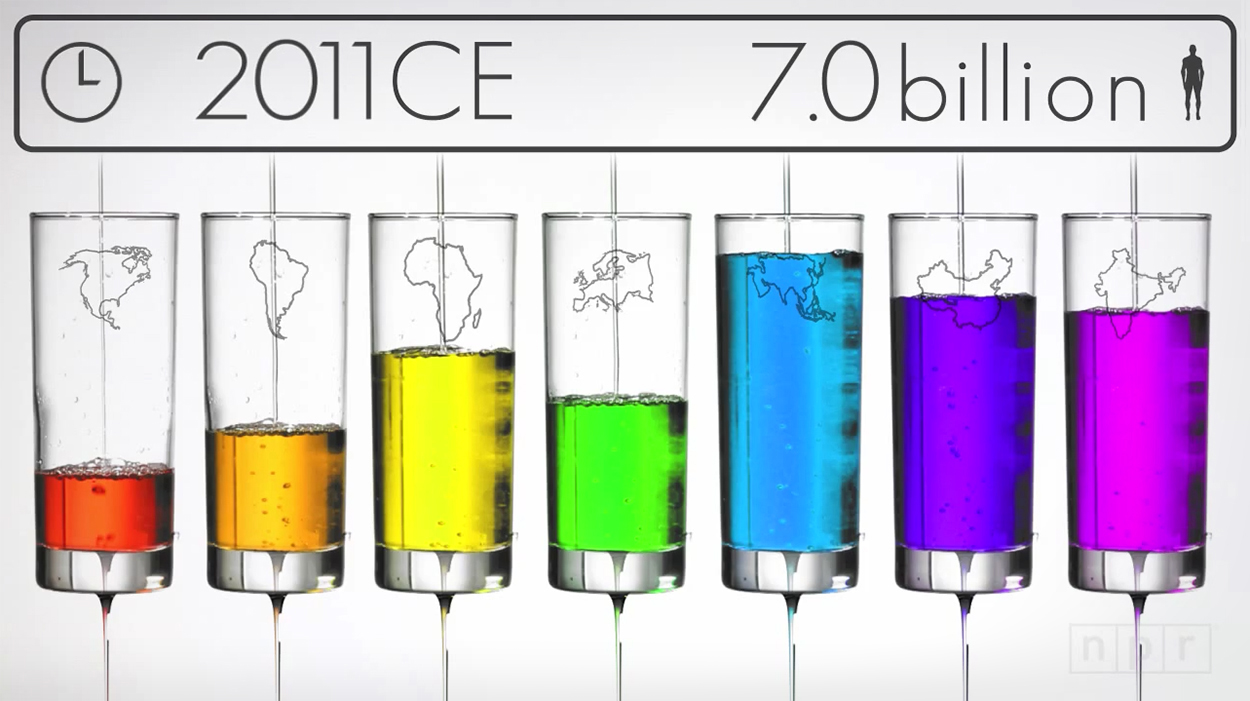

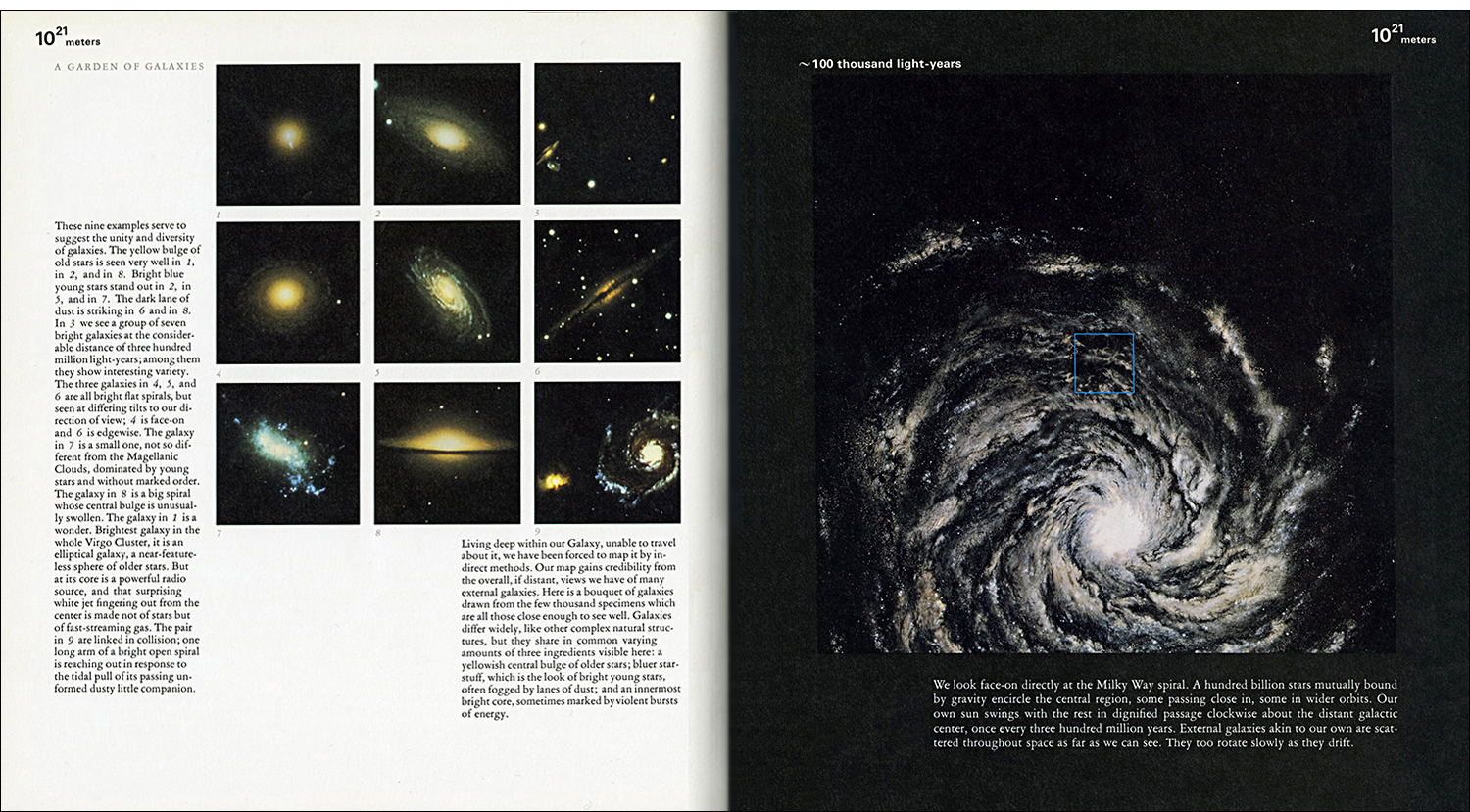

The counterpoint to this post, “Big numbers:” https://wp.me/p7LiLW-2Wk

A related post about scale, “Powers of Ten:” https://wp.me/p7LiLW-21z