COMPUTER INFOGRAPHICS ARRIVE ON THE SCENE.

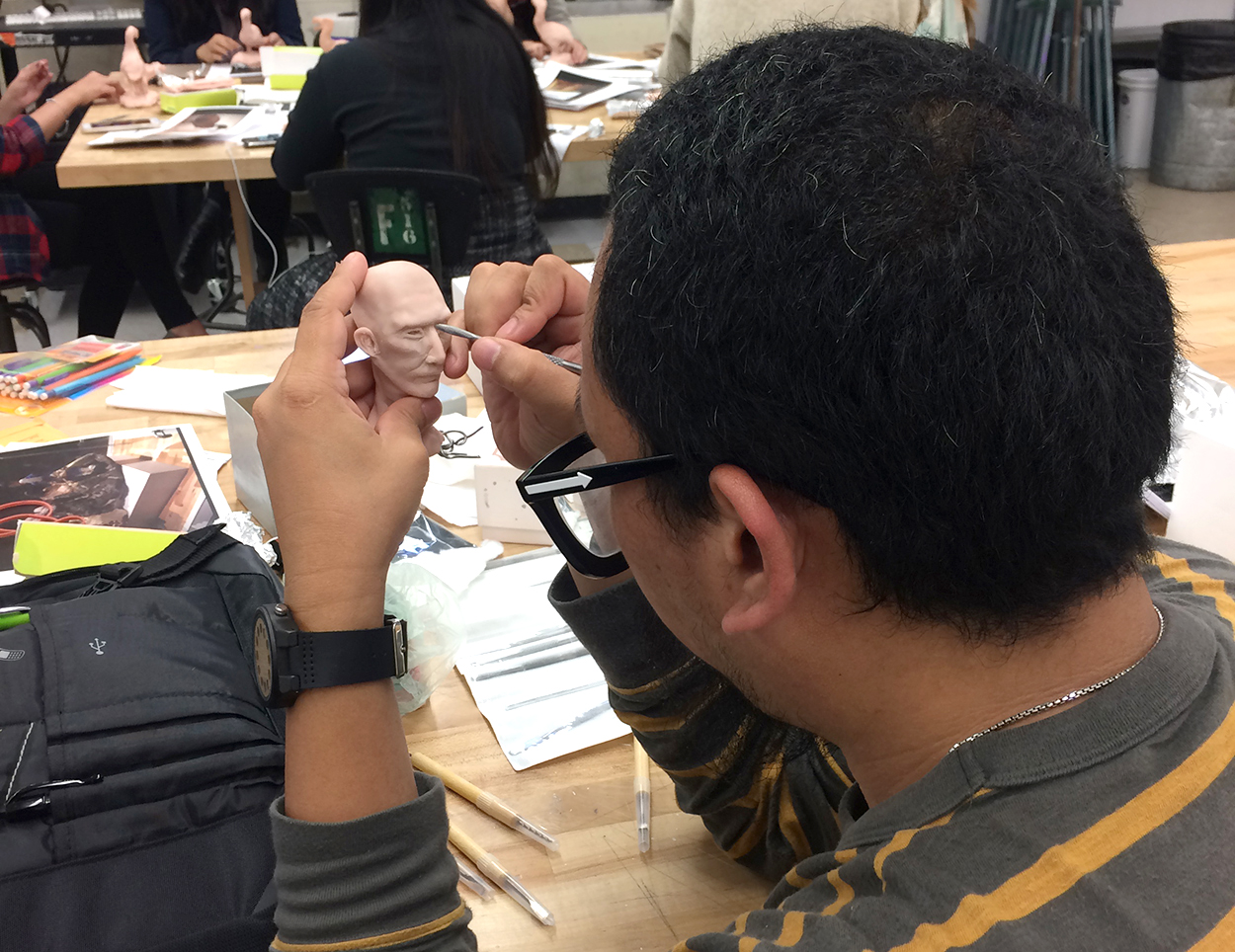

A guest post by a digital news graphics pioneer, Karl Gude, who is now a professor in the College of Communication Arts and Sciences at Michigan State University. Karl is Director of the Media Sandbox.

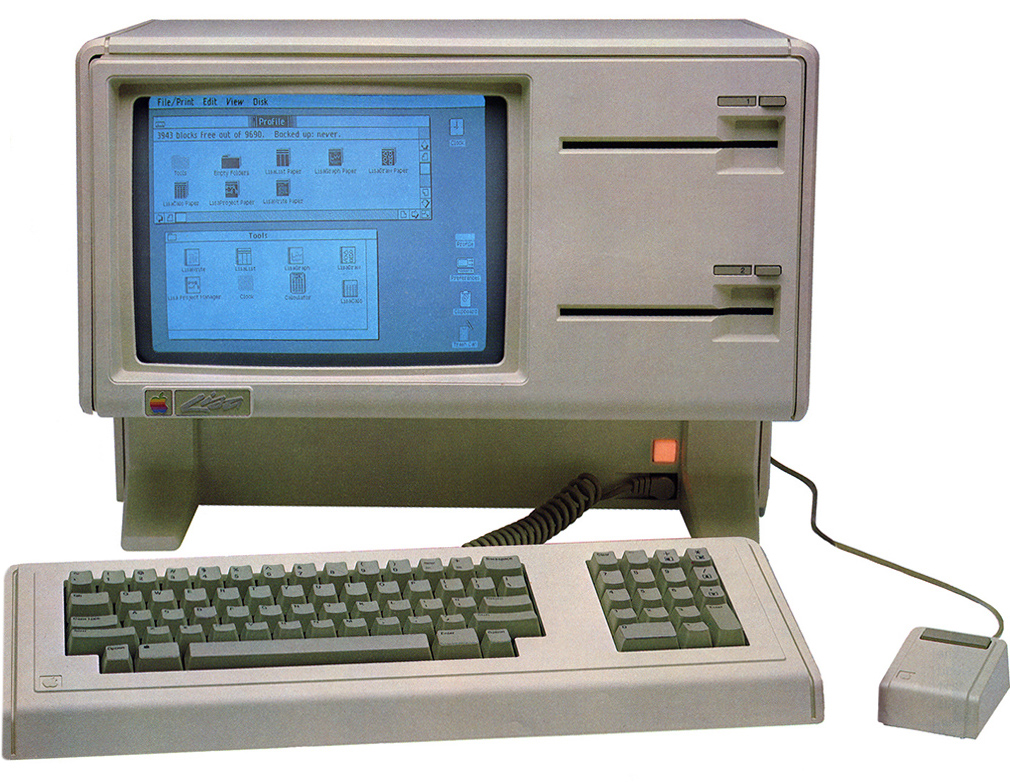

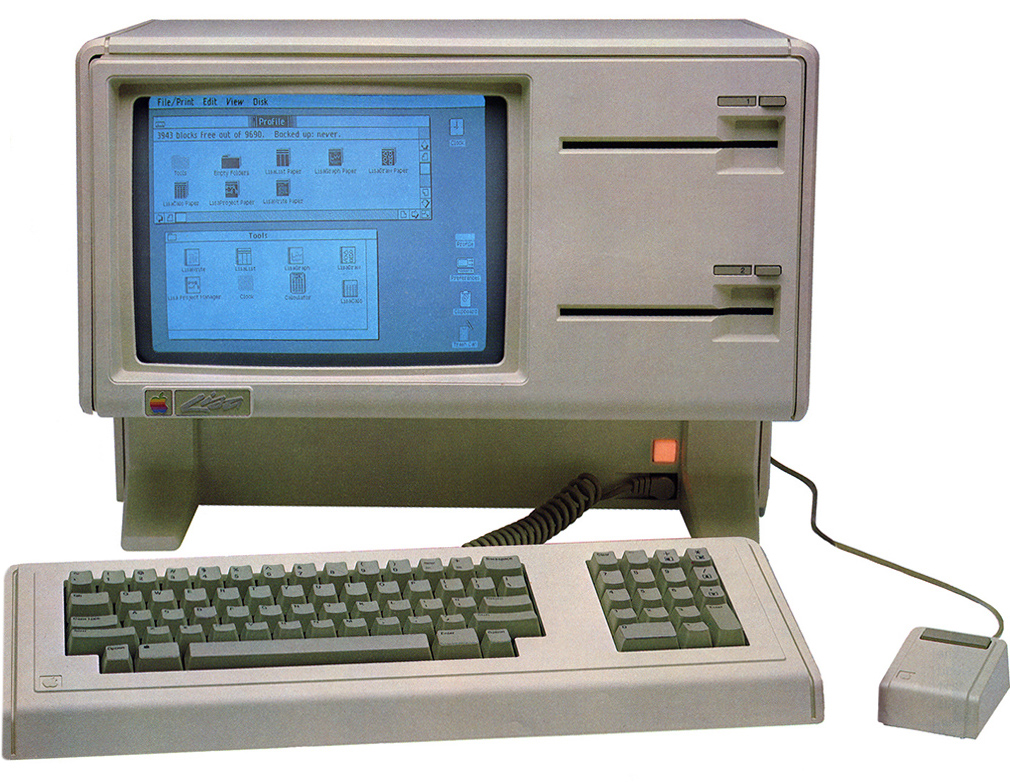

(Above: State-of-the-art in 1985, the Apple Lisa. It cost $24,000 in today’s money.)

Apple to the rescue

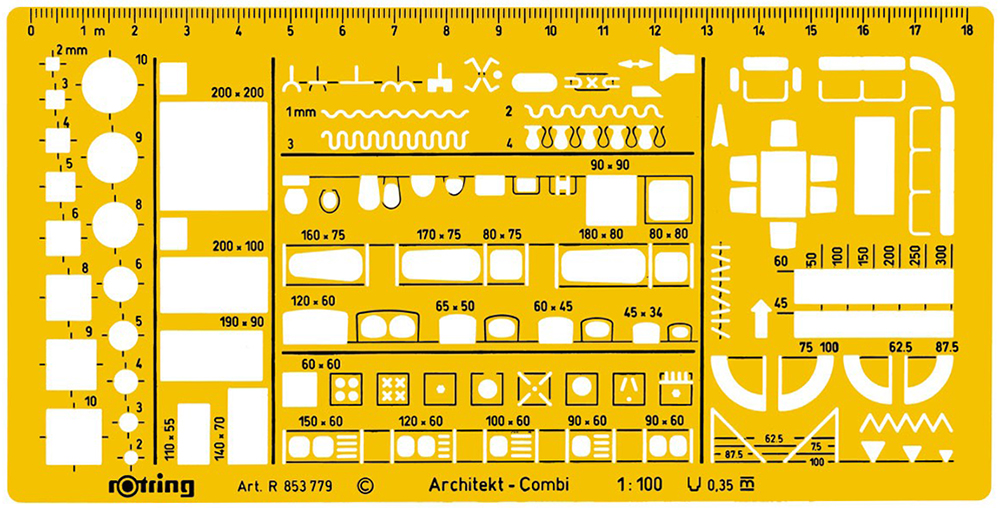

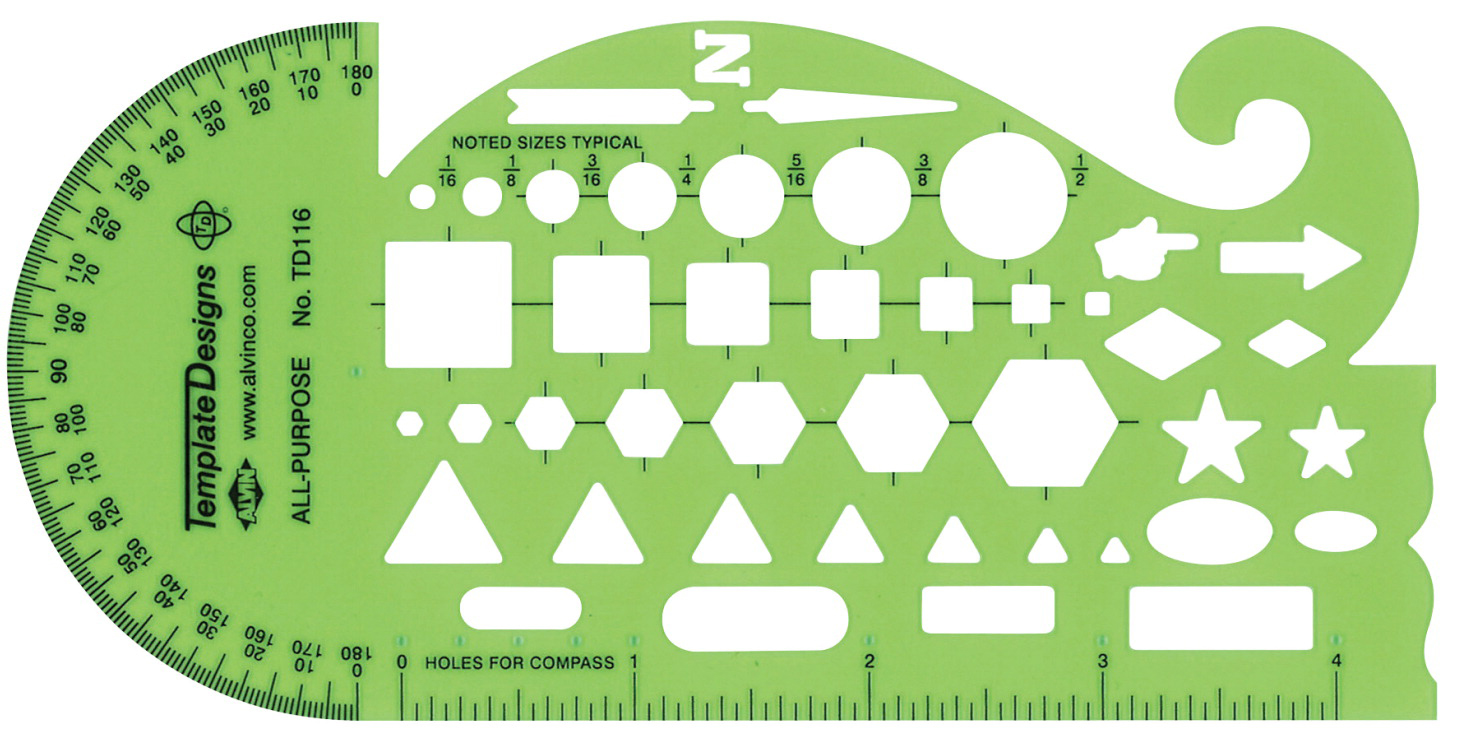

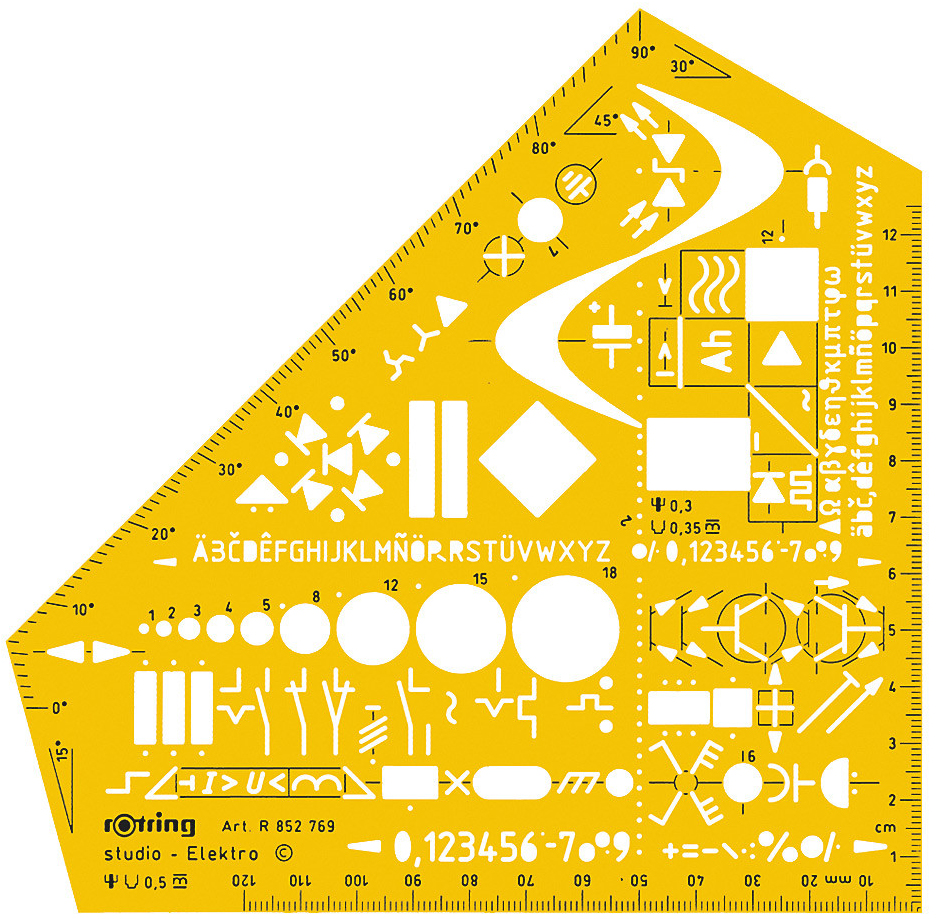

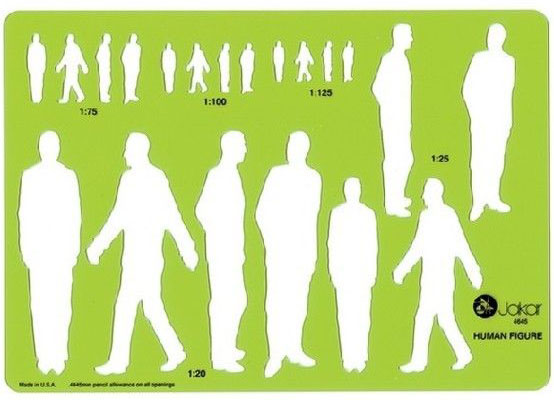

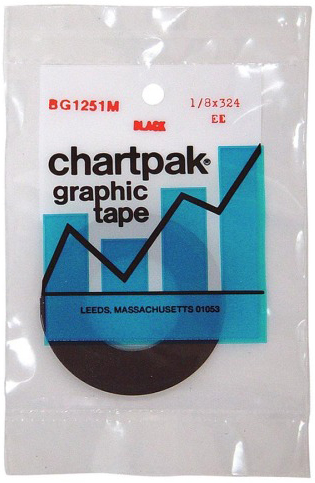

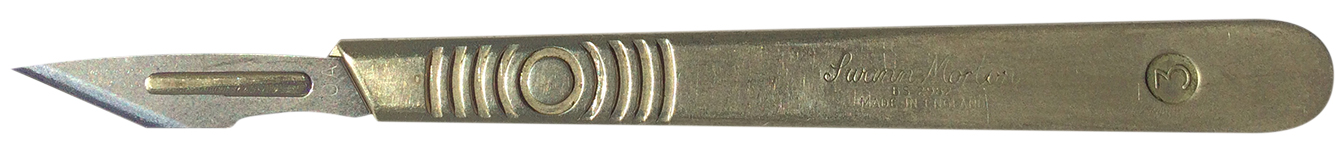

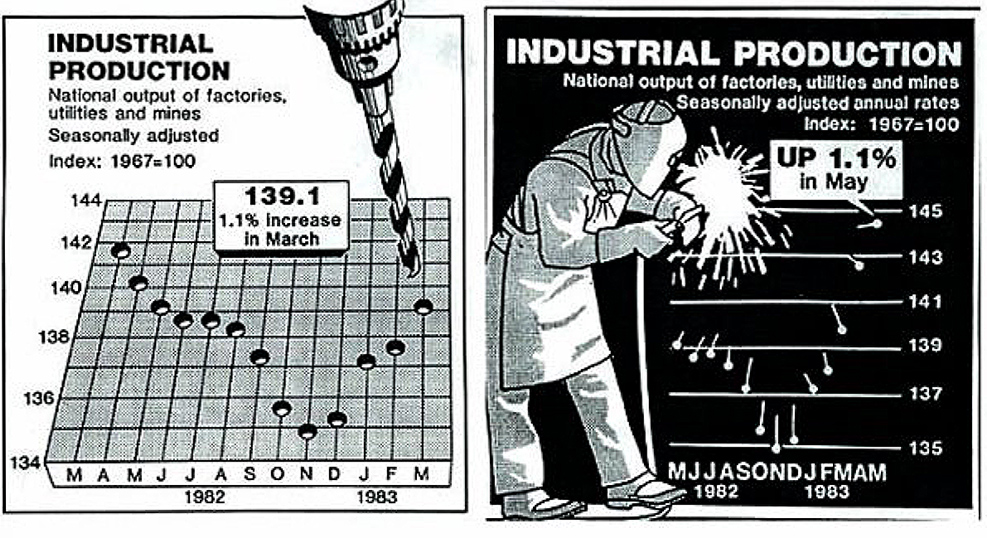

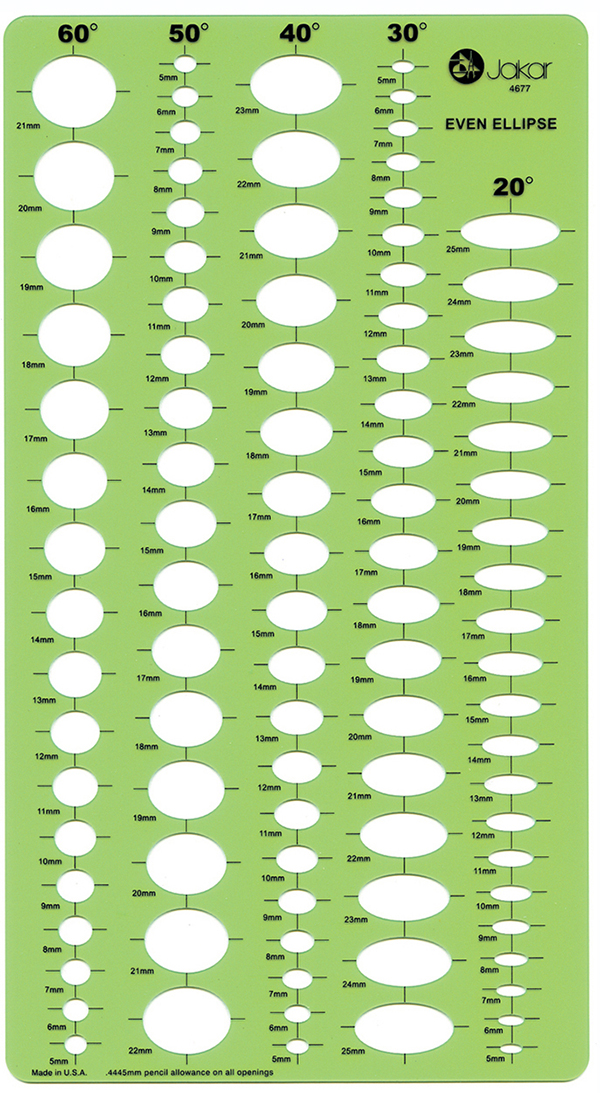

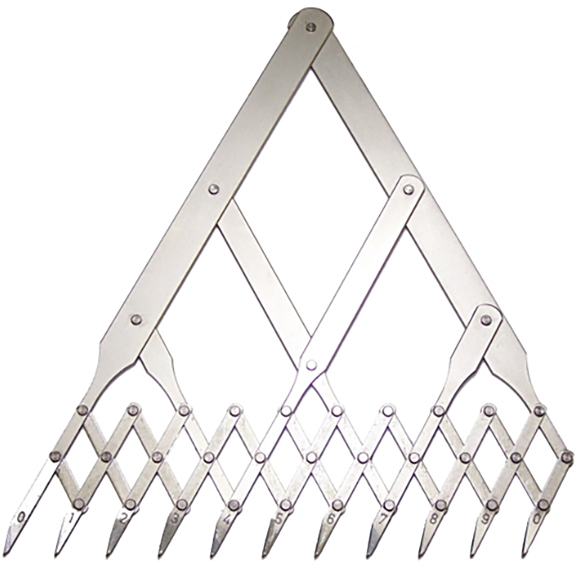

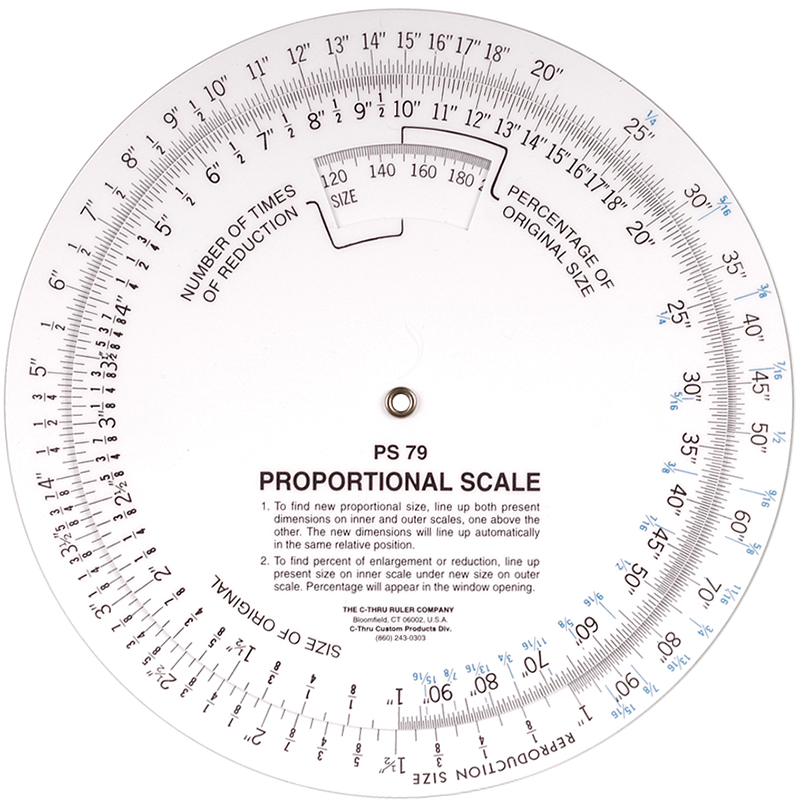

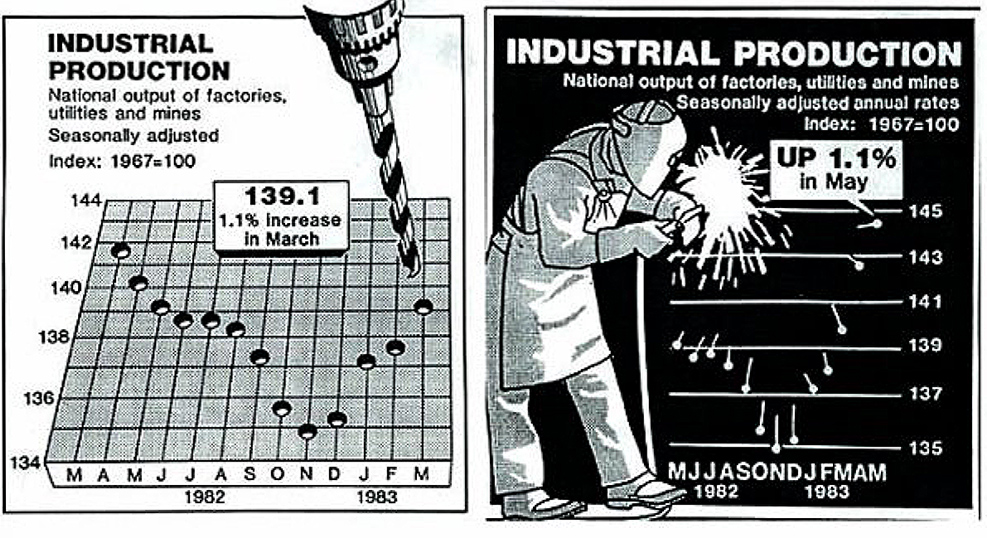

Grrrr… As a news artist working in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I hated plotting graphs by hand, like the ones below, (my boss wanted me to make charts like “Nigel Holmes in Time!”), and I made a lot of them. My fingers were black with ink and nicked by X-Acto blades. But by the mid ‘80s, there was a bright light on the horizon: Apple was making computers that could plot a graph with the click of a mouse.

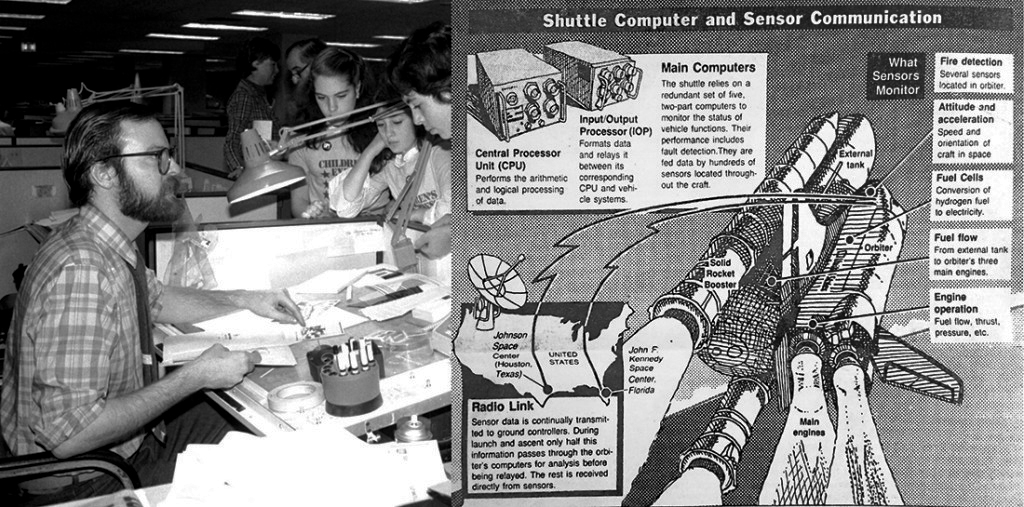

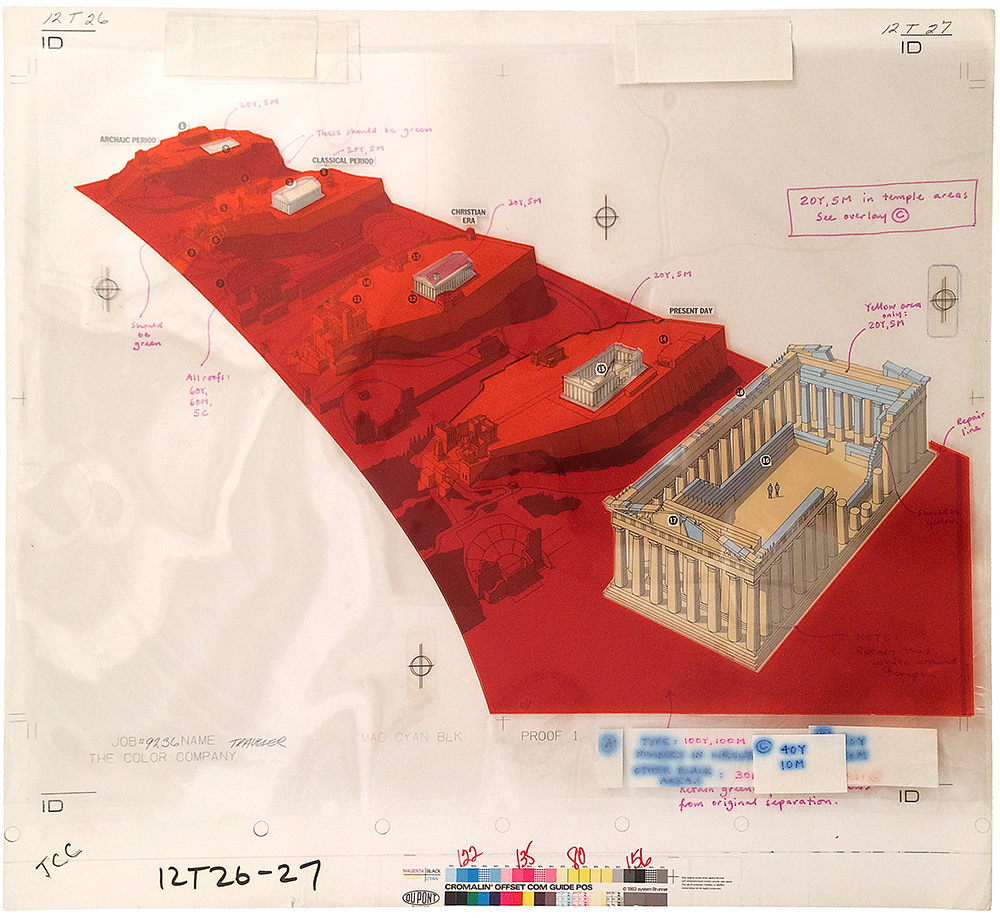

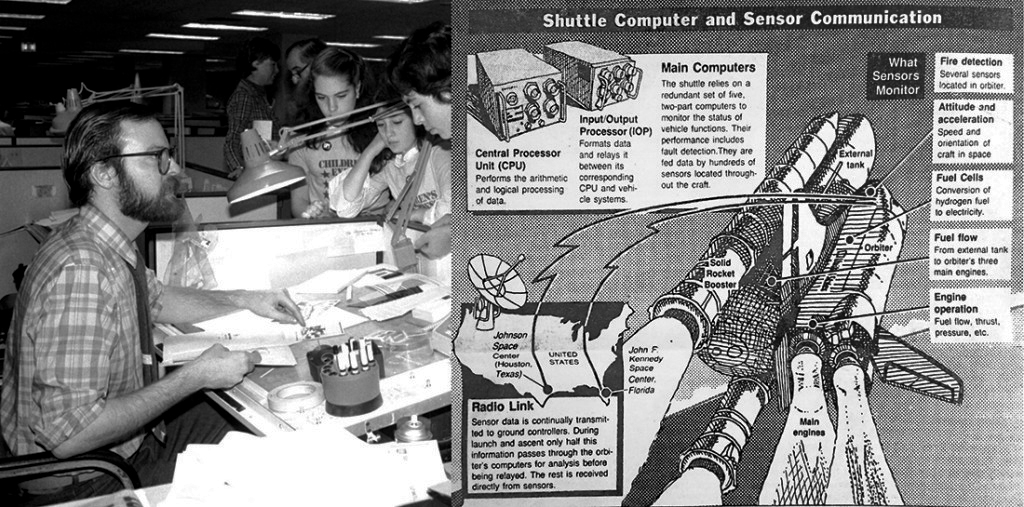

United Press International in the 1980s. All news graphics were drawn by hand.

Life with Lisa

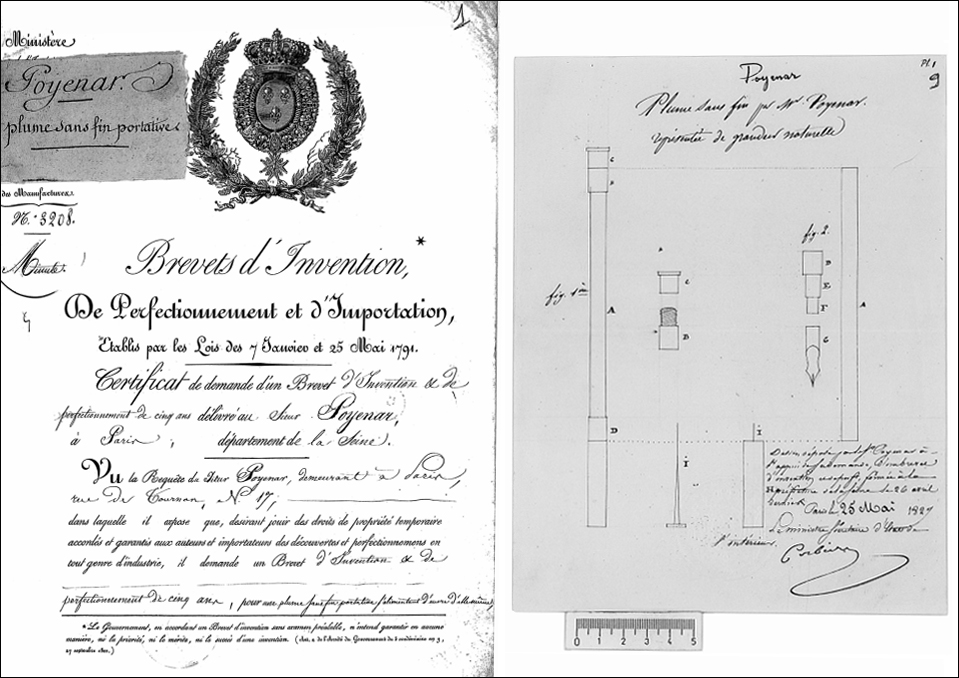

In 1985, I was working for the news agency, UPI, in Washington, D.C., which sold infographics to newspaper clients. We purchased two Apple Lisa computers which could generate simple maps and charts. Apple flew executives out to help us set them up, including Apple iconographer and designer Susan Kare (http://kare.com). Her icons for the operating system are shown below. Apple was excited that the news industry was interested in their products, and if UPI used their equipment, our 1,600 newspaper and TV clients would also have to use it to edit our graphics, if only to delete the byline!

Back to analog

I moved to the New York Daily News as their News Graphics Director in 1986. Unfortunately, it was back to the drafting table, and the old ways of doing things, but not for long. The editor was against spending money on graphics technology, but he agreed to allow me to rent one Apple Macintosh, or Mac (a bit better than the Lisa for graphics), to create infographics for a special series we were doing on transit in New York. The Mac was a crowd-pleaser, and when the editor saw what it could do he allowed me to purchase six of them. Out went the art tables, and in came the complaints. Most of the staff didn’t like this new way of making graphics and drawing, but before I could see how it all turned out, I moved to the Associated Press.

The Associated Press goes digital

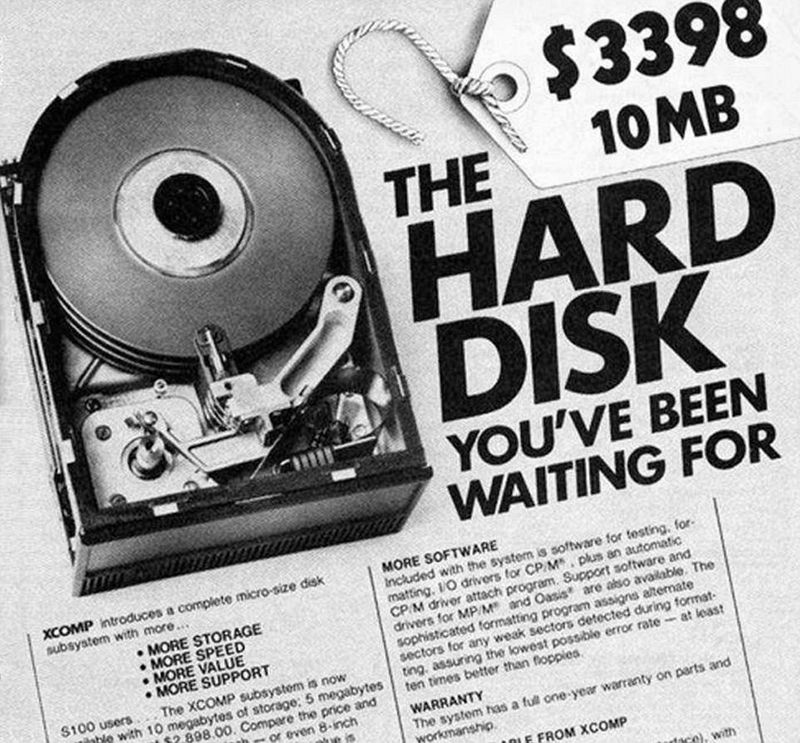

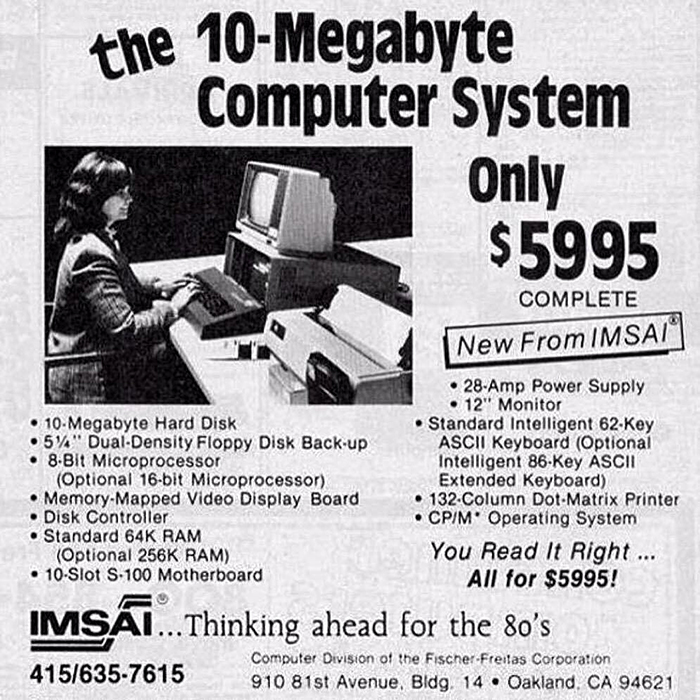

Again, drawing tables! But, AP was already considering Macs, and the transition from drawing tables to computers happened quickly. I felt sad though, at the sight of about 12 battle weary, ink-stained and cut up drawing tables lining a long hallway waiting to be shipped to a warehouse. They were replaced with flat desks with Macs sitting atop 20-megabyte (!) hard drives.

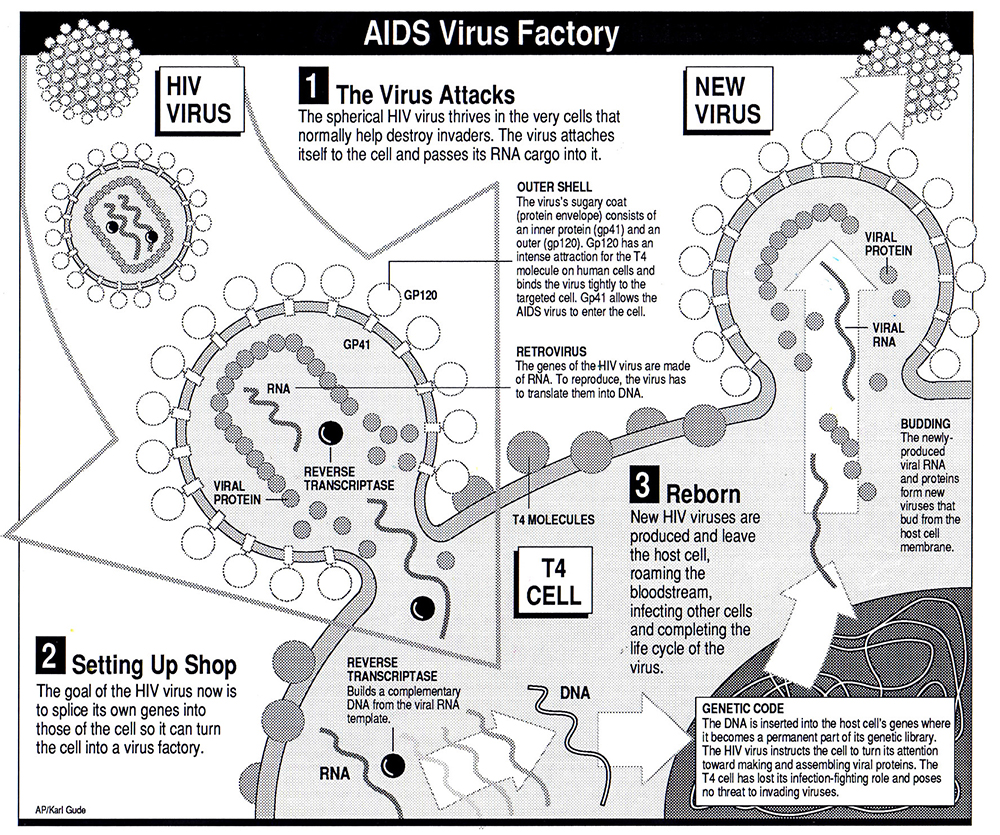

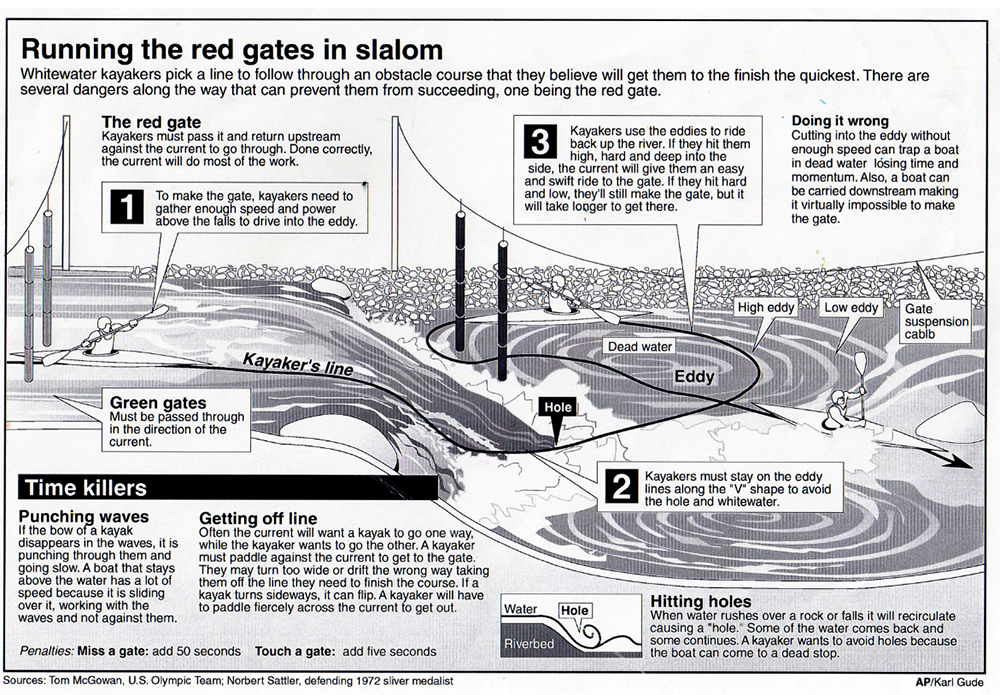

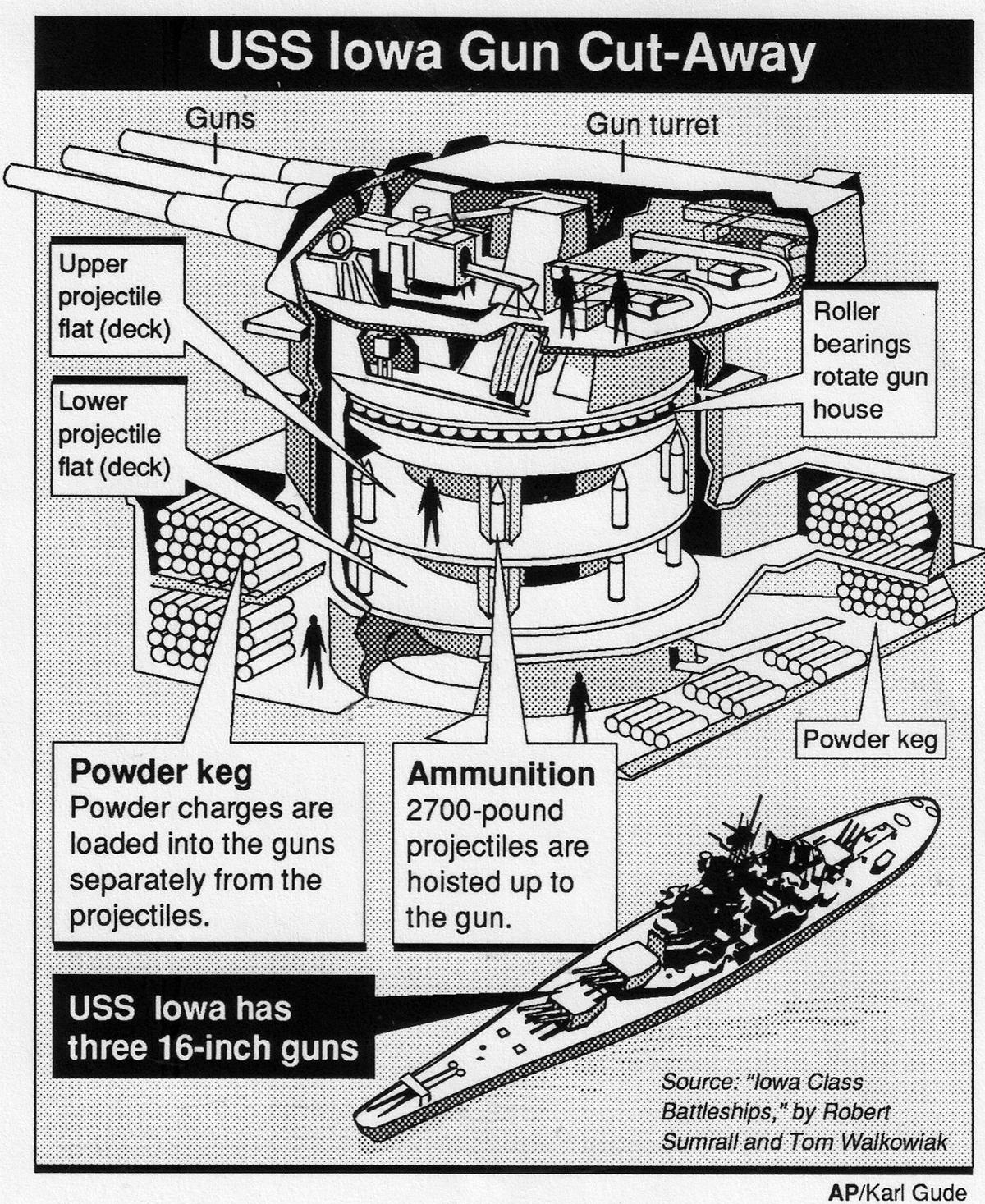

One of my early Mac graphics drawn in Claris MacDraw 1.9.6, March 1988.

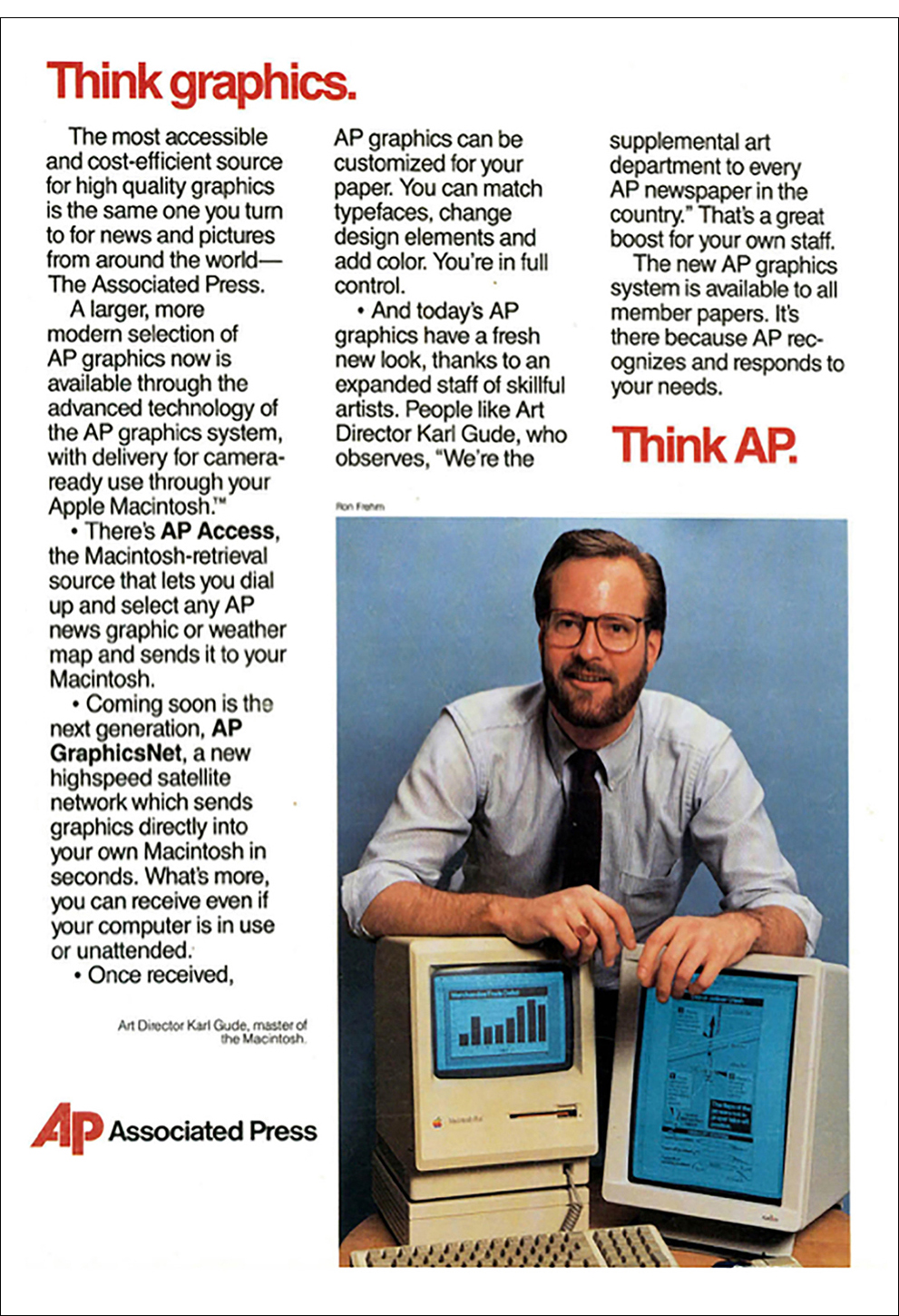

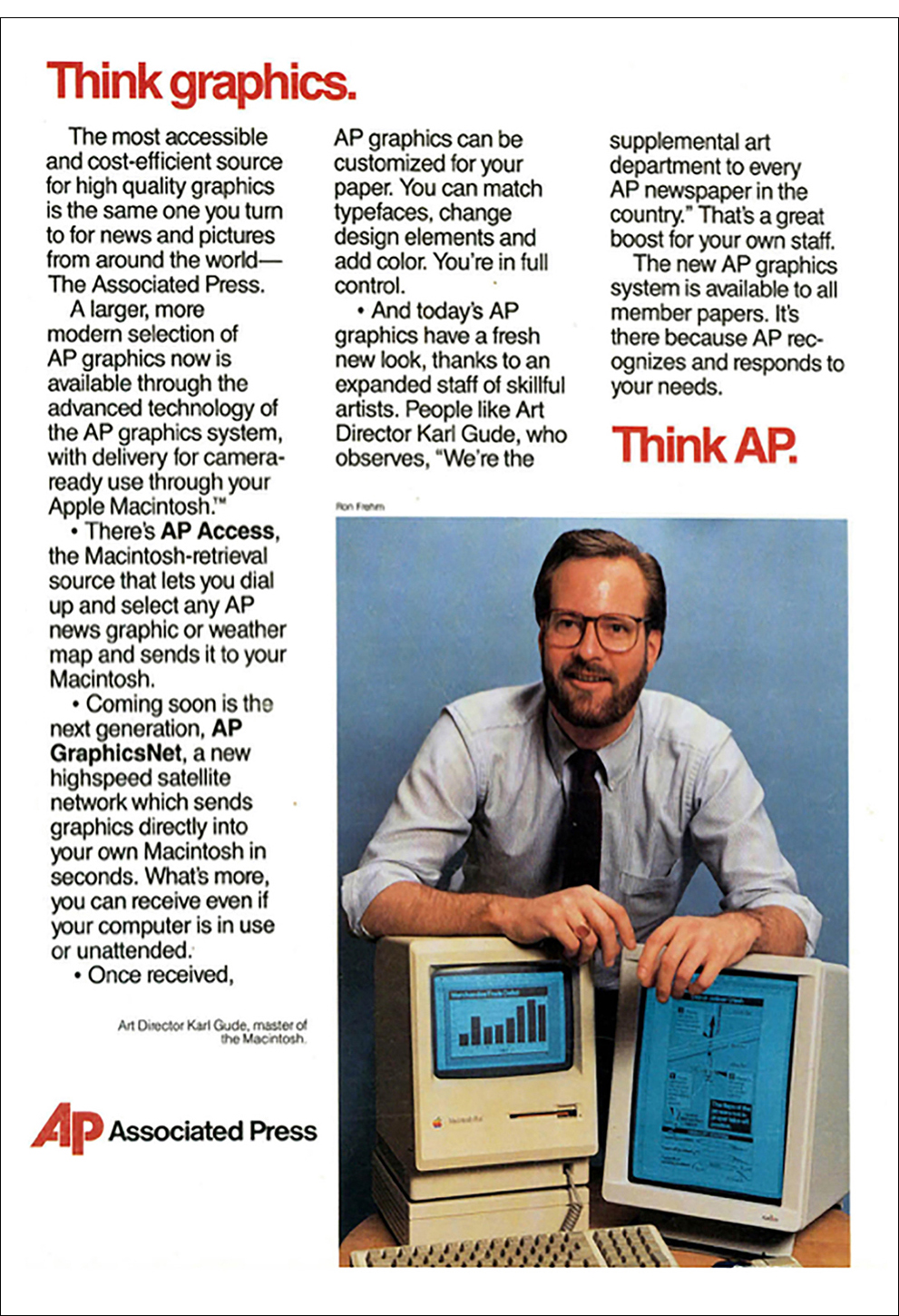

AP leads the way. (Editor’s note: Notice that Karl is “master of the Macintosh”. You can’t beat that.)

The first portable Mac

If you were to shrink every tool on a cluttered drawing table and cram them into a tiny little box, you would have the Macintosh Plus. Because the computer was so light and portable, Apple designed a backpack so that it could be easily taken places, which was a dream for me back in 1987. As a news artist, it was hard to visit the scene of a breaking news event and cover it live in the same way a photographer could with a camera. The best I could do was to go there and make sketches (visual notes) to use as reference for a drawing that I would complete back at the office.

The traveling computer. Just a little larger than an iPad! Karl holding the bag a few days ago.

Before Apple’s swanky backpack existed, I used a cardboard box. There was a terrible accident where a building under construction collapsed killing a number of workmen in Bridgeport, Connecticut, which was about 35 miles from the AP offices in New York, As was the usual drill, I found myself explaining to a photographer, who was rushing to the scene, which photos I needed him to take for me as possible reference for a diagram. It was then I realized that I could go with him! No longer tied down to a drawing table, I threw my Macintosh into a cardboard box, and hopped in the car with him. The Connecticut Post was nice enough to give me a desk to work on (thanks Rick Sayers!), and my Mac was the first one they had seen in action. The diagram I made that night, explaining the process workers were using to build the doomed building (called “lift-slab construction”), was transmitted over a phone modem directly from the Post to AP in New York, who then routed it to hundreds of newspapers and TV stations around the country. Hours were saved in the making of the graphic, which made our subscribers very happy.

Drawing programs: vector or postscript?

In the early days, before scanners came along, drawing on Macs was heavy going. We used the vector-based MacDraw program, which was easy, cheap, and already in every newsroom. Because we were a news agency that supplied graphics to 2,000+ frugal news organizations, we had to stick with MacDraw much longer than we had wanted.

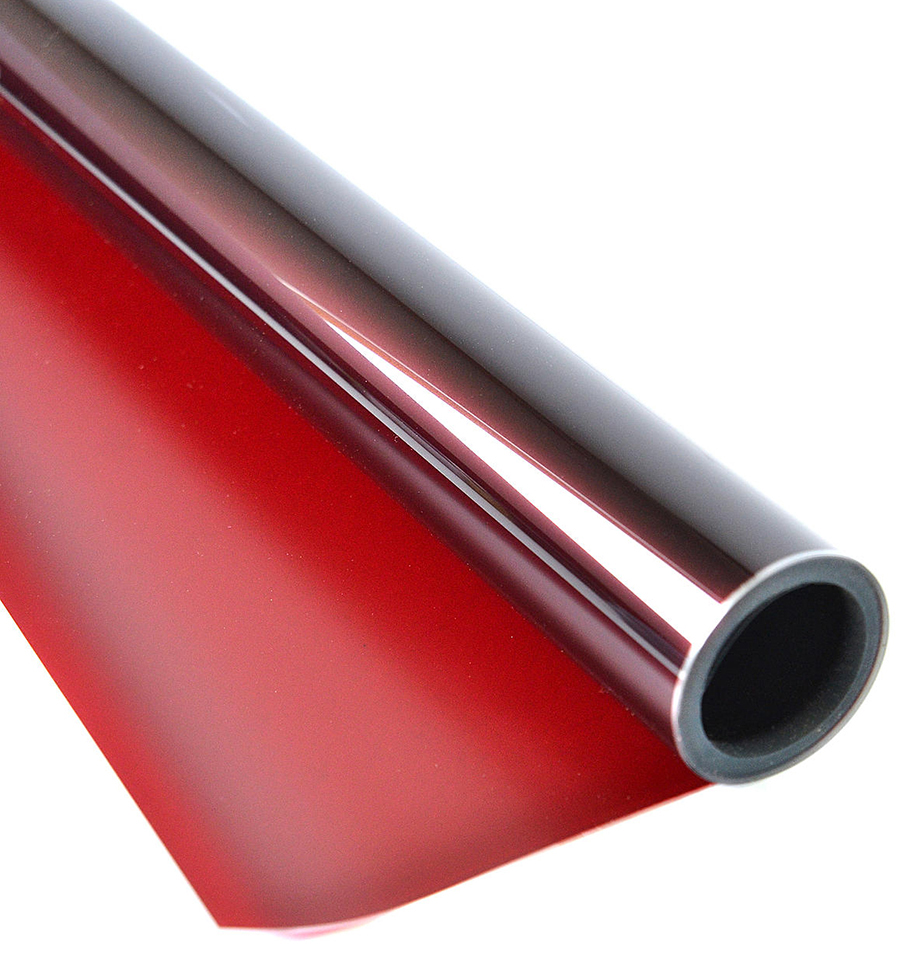

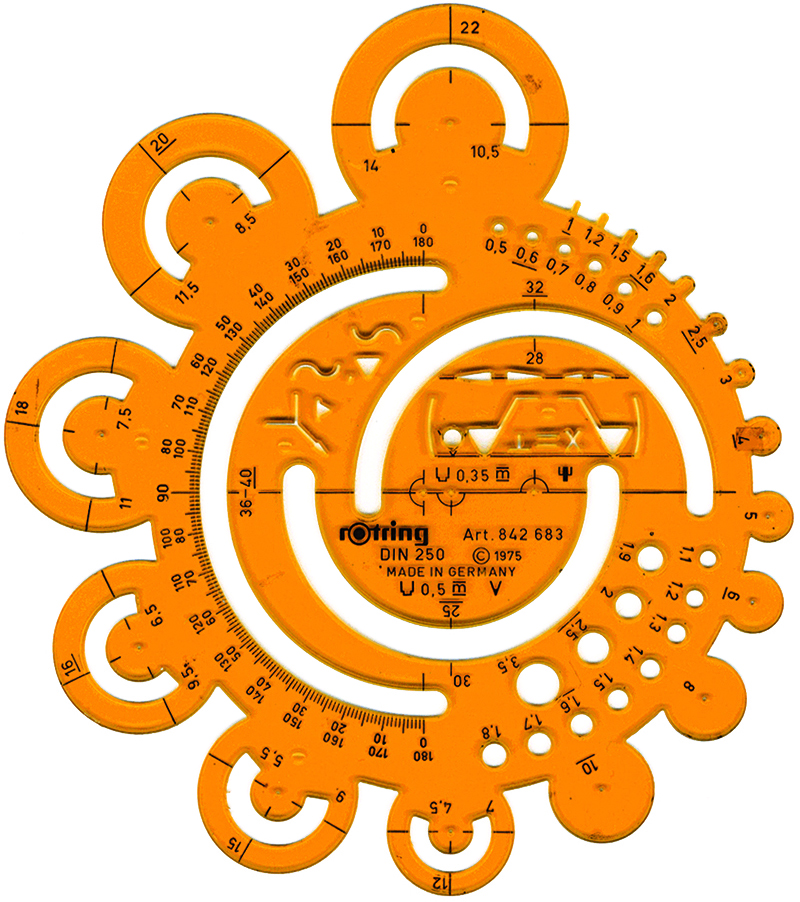

We would sketch out our drawings on paper, and in order to get them into the Mac to finalize them, we followed this process:

- Size the drawing (or photo reference) on a copy machine to about the size of the tiny Mac screen.

- Trace the drawing (or photo reference) with a marker pen onto clear acetate.

- Tape the acetate to the Mac over the screen.

- Trace the image with the mouse (much like drawing with a bar of soap) by clicking around the acetate drawing without moving your head (otherwise, your drawing would be distorted).

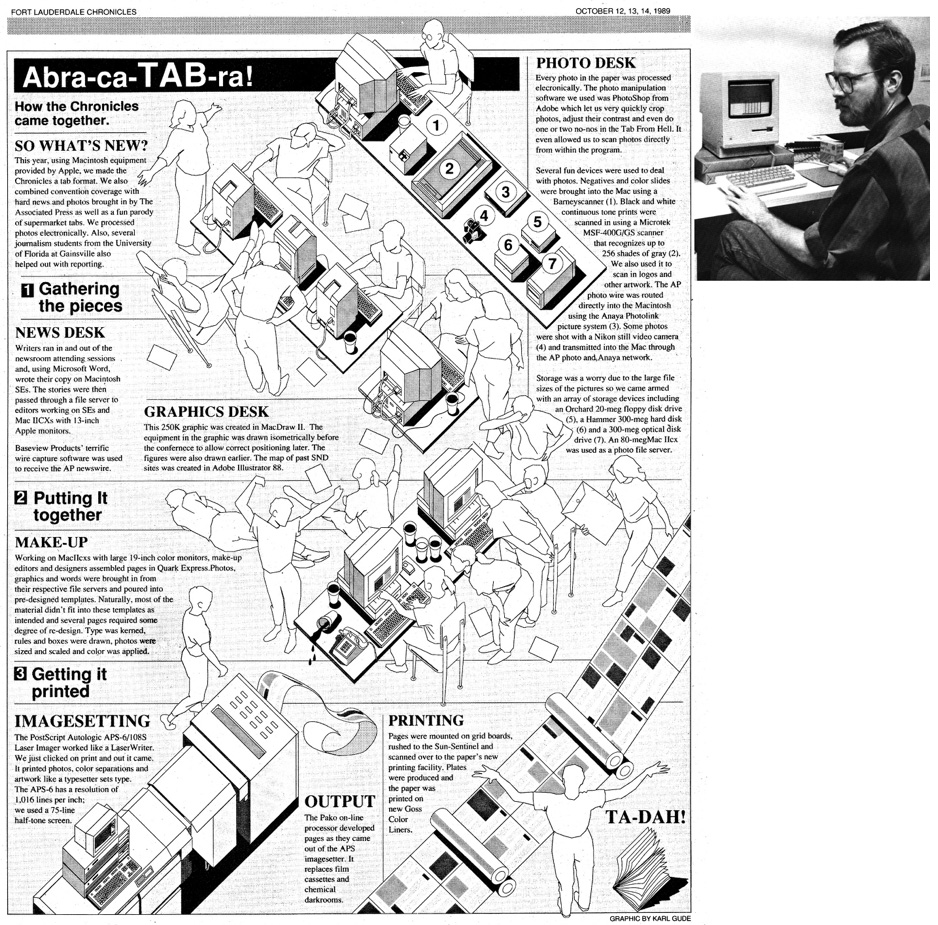

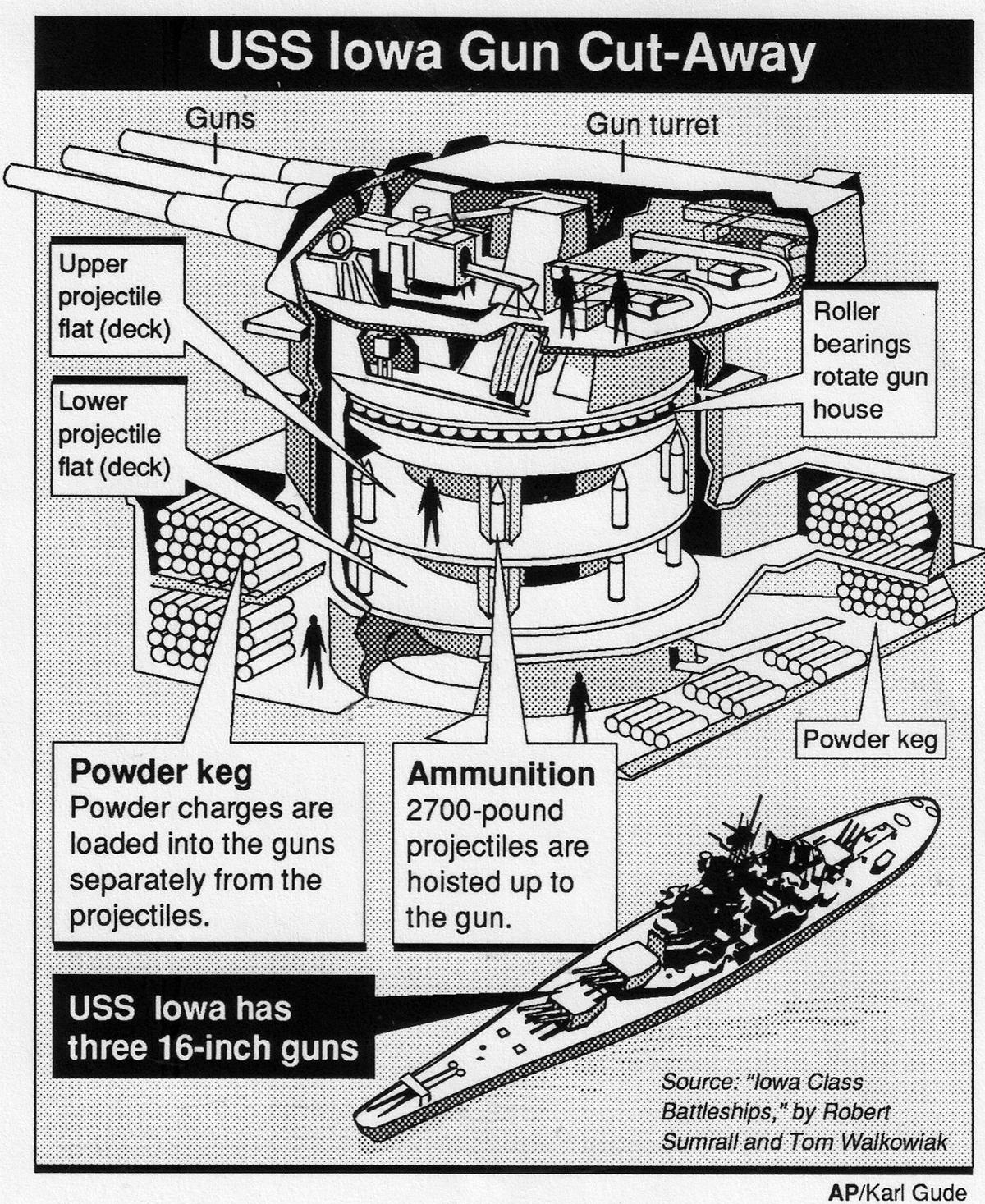

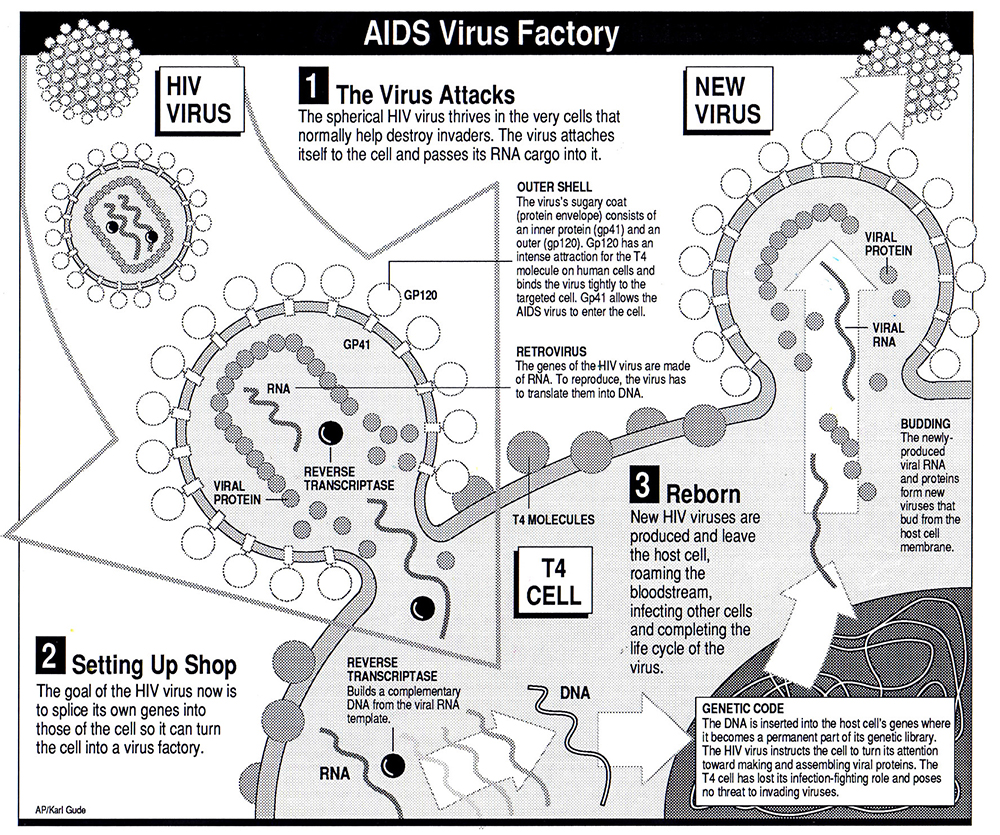

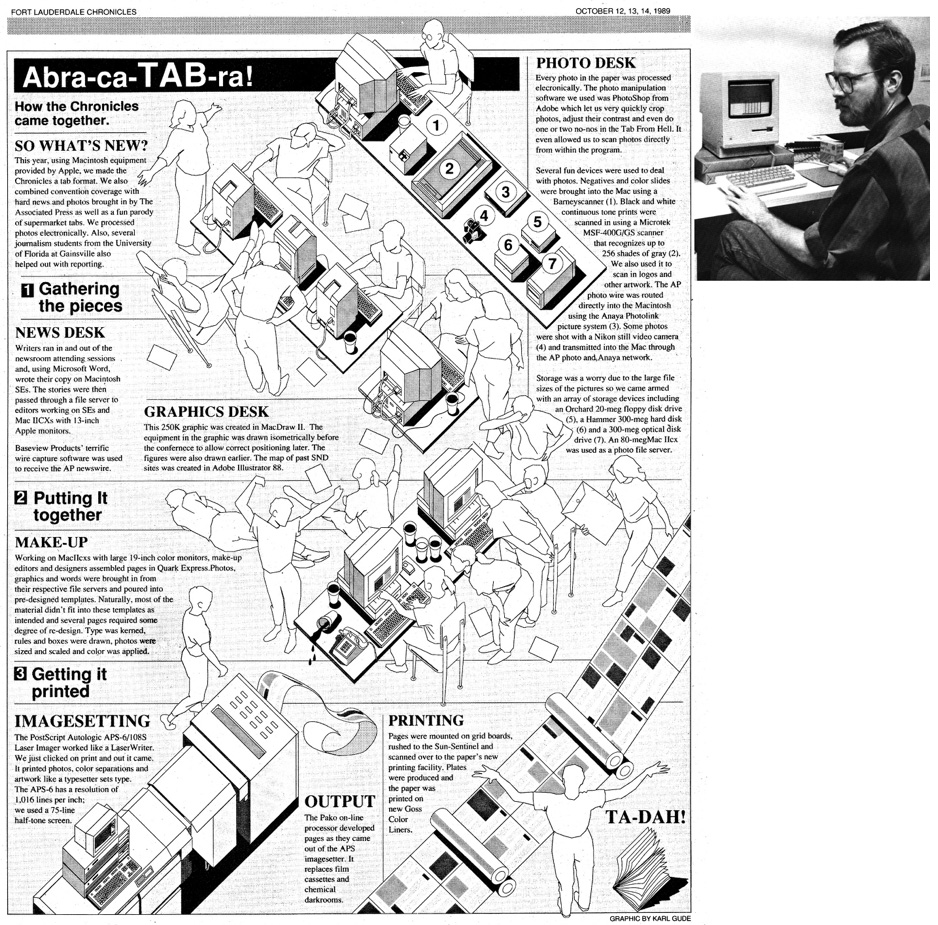

The equipment in this illustration was drawn directly in the Mac SE using MacDraw II, but the people, which my wife posed for, were drawn using the method detailed above.

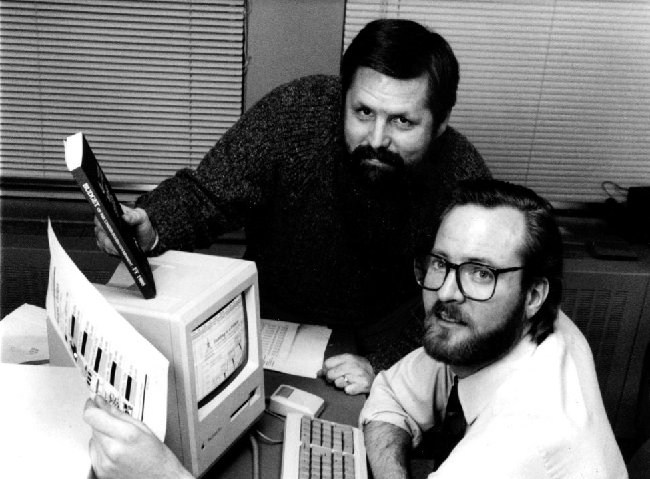

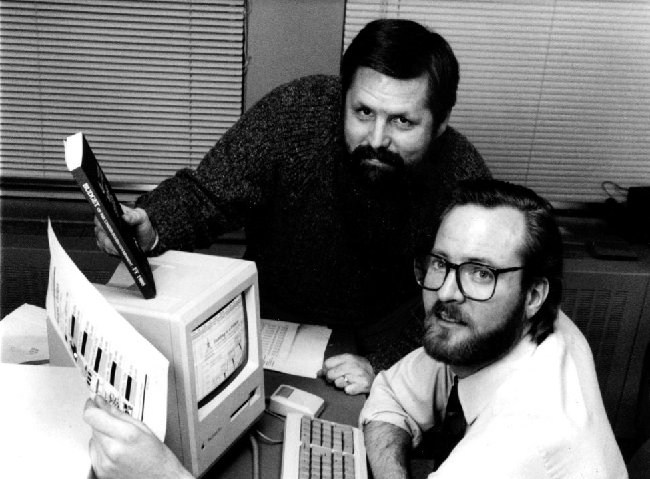

Covering elections with the Mac meant sending graphics directly to papers through Mac-to-Mac- dial-up instead of over a slow, bogged down photo network. Here I am in D.C. with AP’s Brian Horton to cover the 1988 elections.

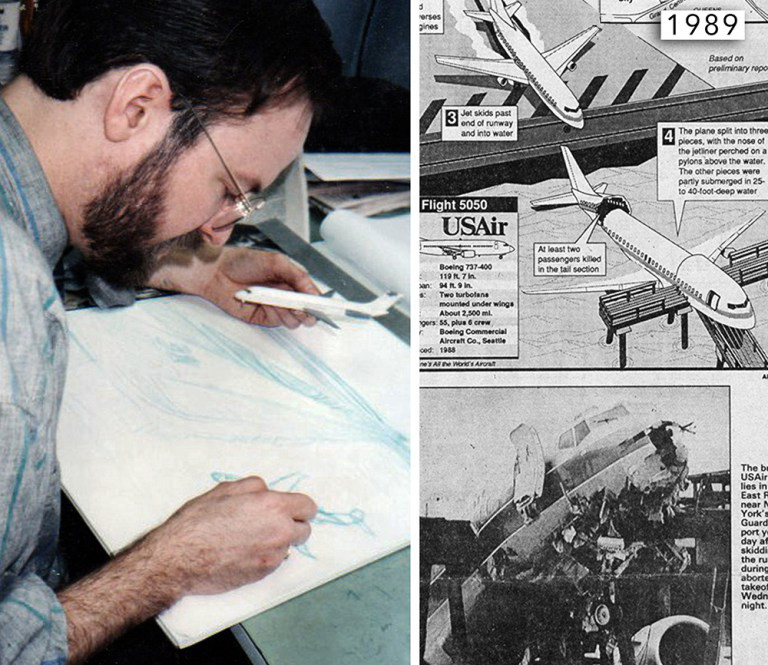

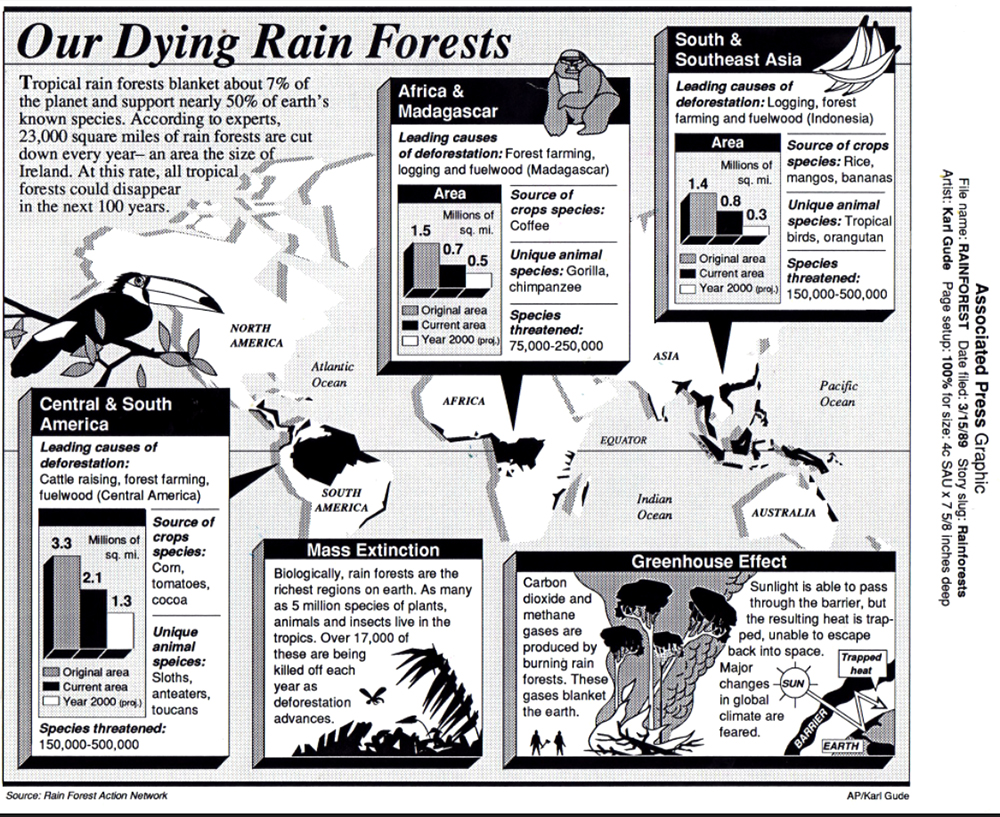

1989 MacDraw graphic, one of my last with that software.

Superior postscript drawing programs like Adobe Illustrator and Aldus Freehand had come out, but for the Associated Press to switch to one of those meant getting all of our news members to purchase and learn it, and most of the smaller papers resisted this expense of time and money. Also, postscript programs couldn’t read vector images, so entire databases of maps and images would be useless. Eventually, though, we had to make the move. We asked both Adobe and Aldus if they could build into their next version the ability to open and edit vector-based images. Adobe said, “That’s against our religion. No.” But Aldus said, “How soon do you need it?” So, we announced to the newspaper world that AP would be switching to Freehand, and that we could get if for them at a discount. I heard that the Adobe guy who made the “religion” comment was fired for lack of vision.

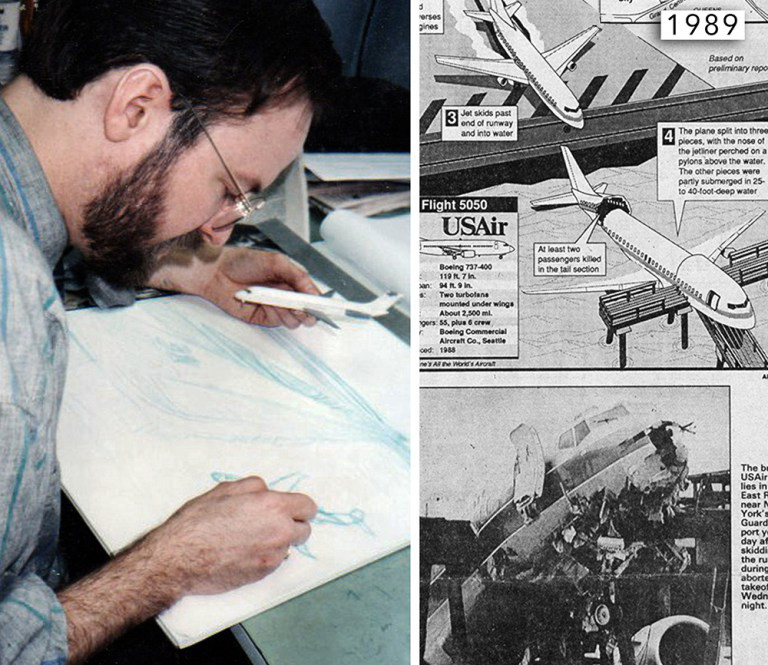

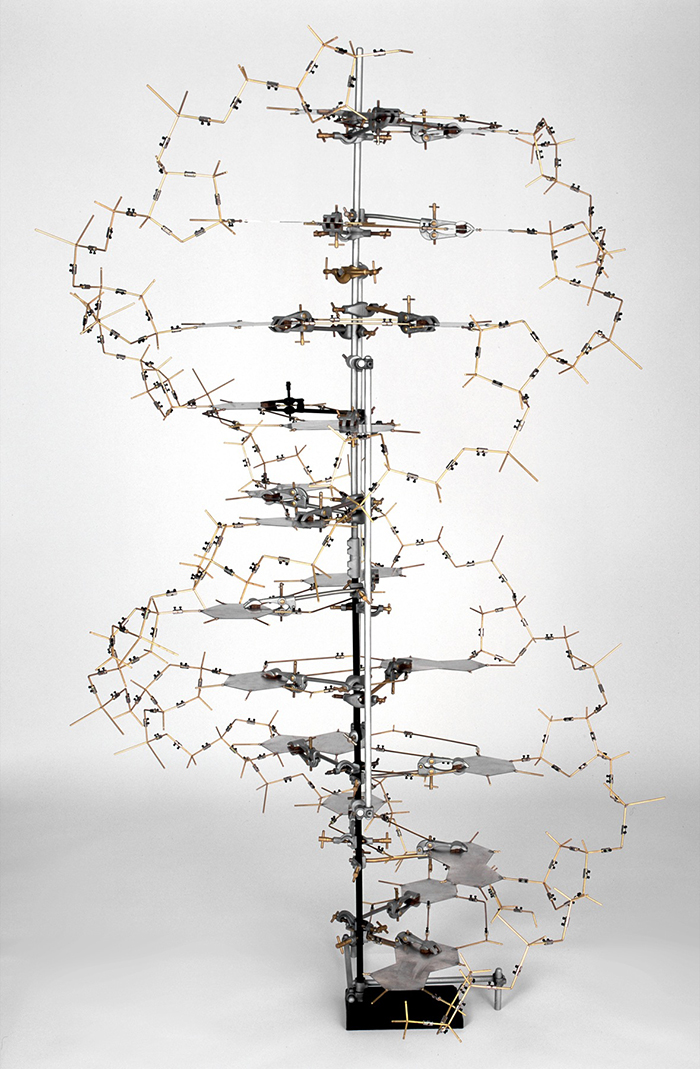

Sketching out a plane crash graphic before drawing it in the Mac. We built lots of aircraft models for reference.

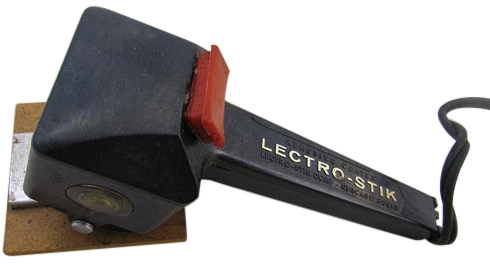

Still, despite all of the awkward limitations, drawing on the Mac still was better than drawing with an ink pen, and pasting a layout with melted wax onto boards before having them photographed and printed. The Mac allowed you to edit your lines and fills, change text easily, move elements around into different layouts, and create databases of elements, like maps, that you could reuse another time. It was heaven.

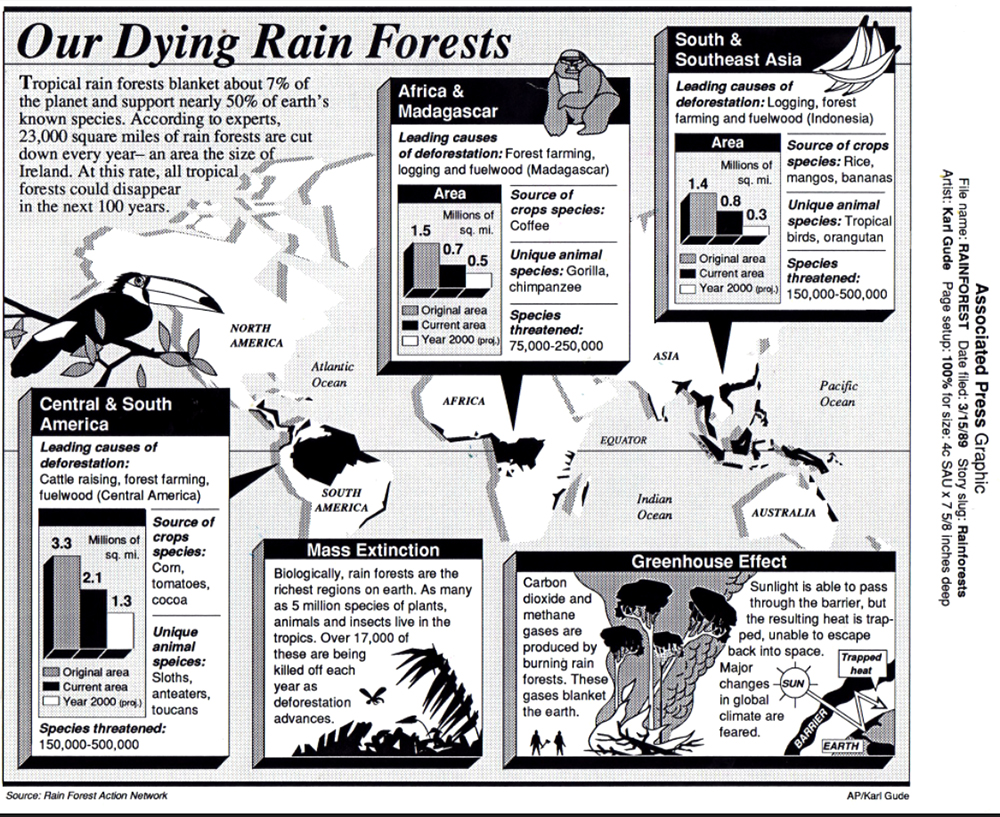

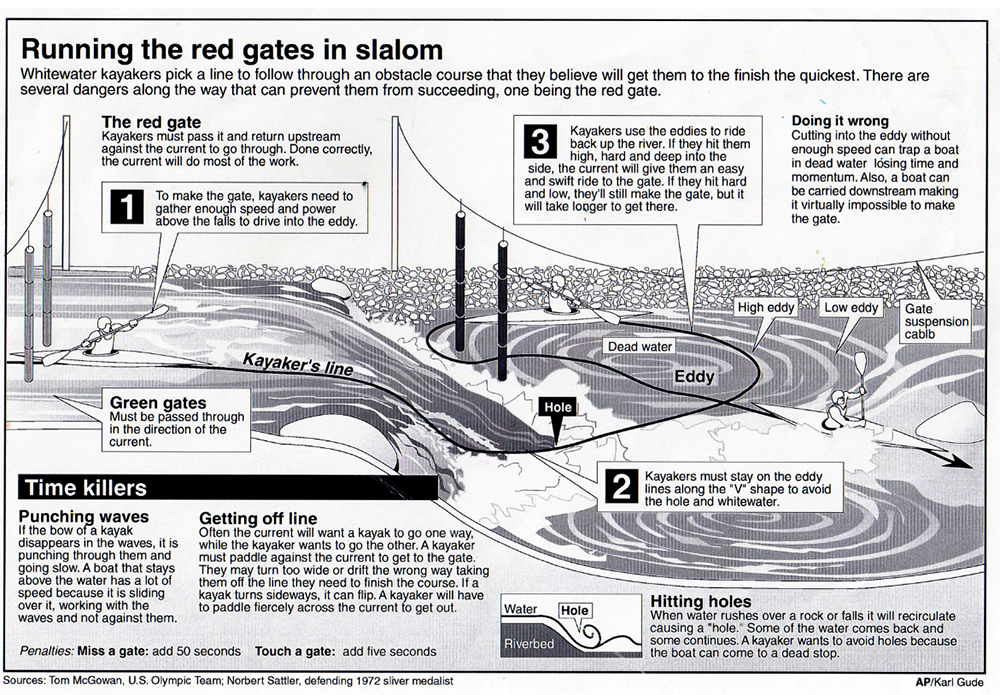

An early Aldus Freehand drawing, 1989. The thick 3D boxes were a bit much. Hey, so were shoulder pads in jackets!

By the early 90s, the Mac and Postscript software, predominantly Adobe Illustrator, had stuck and both were here to stay.

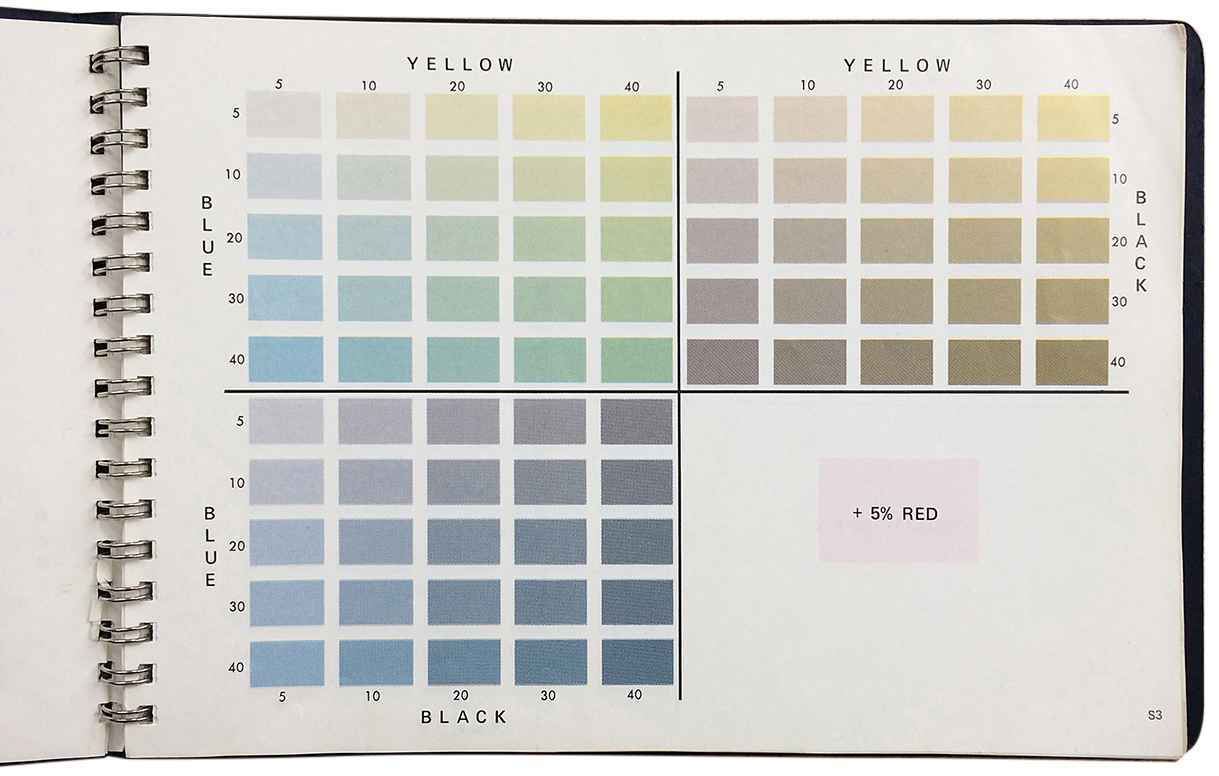

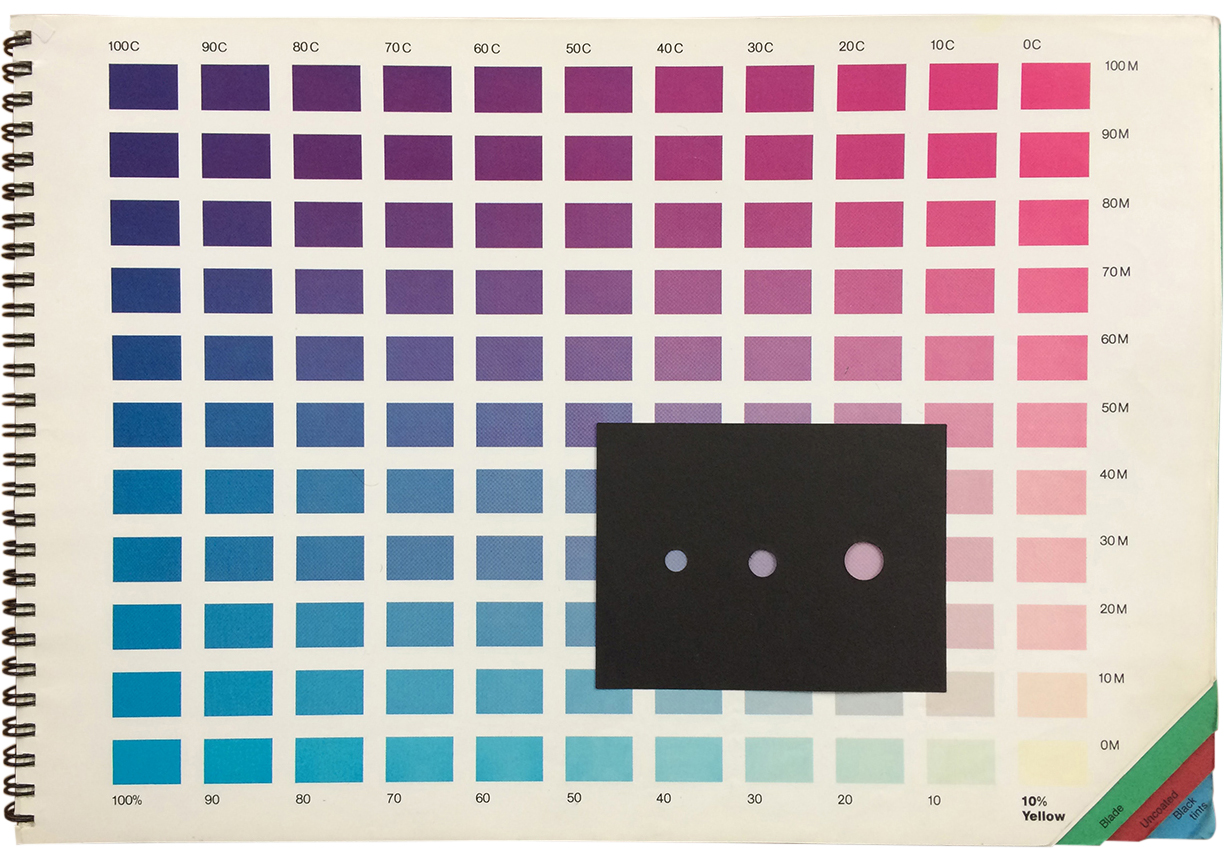

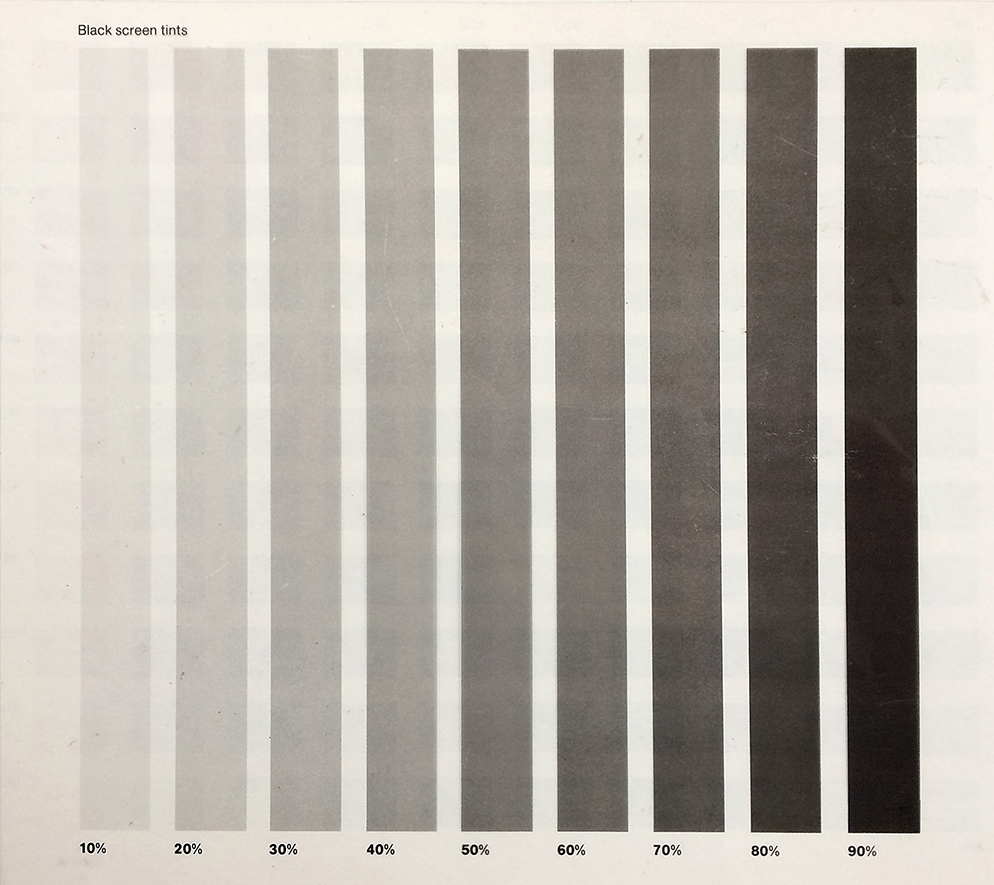

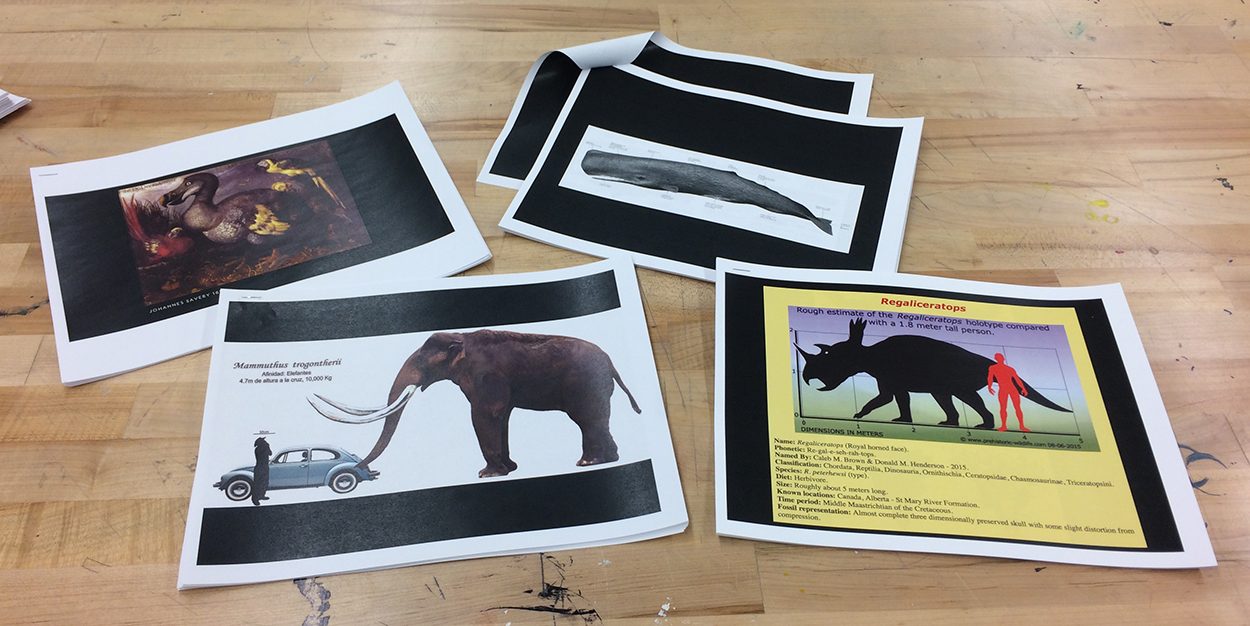

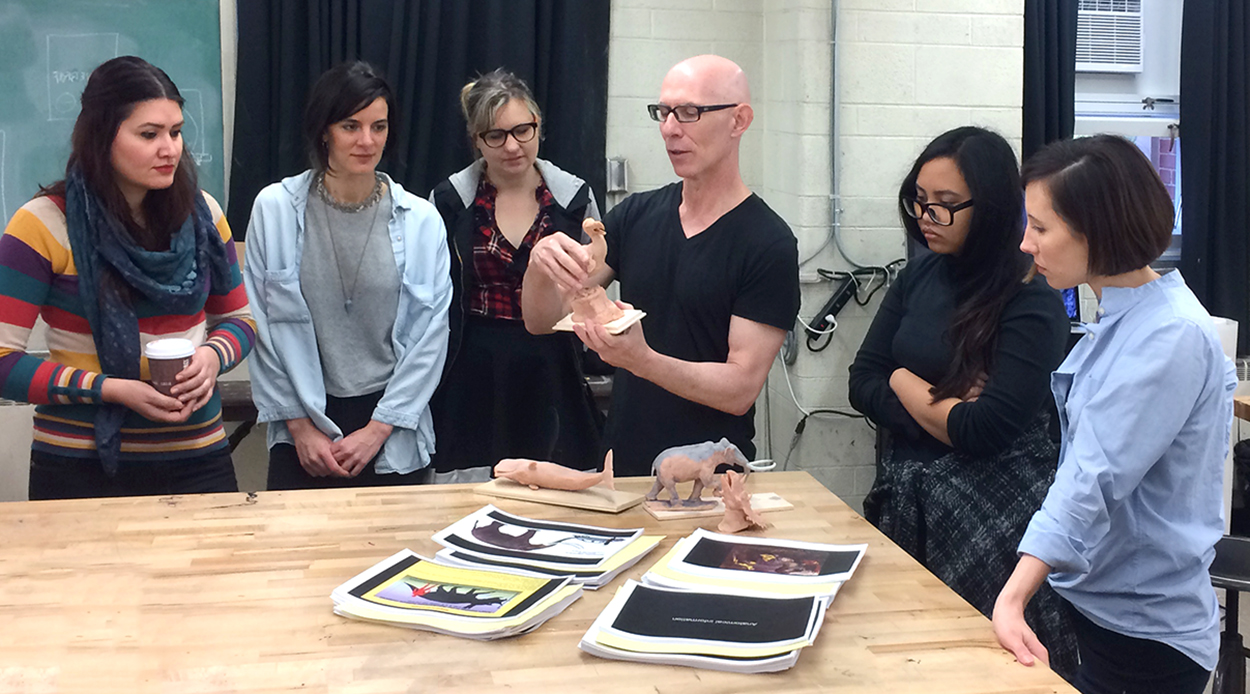

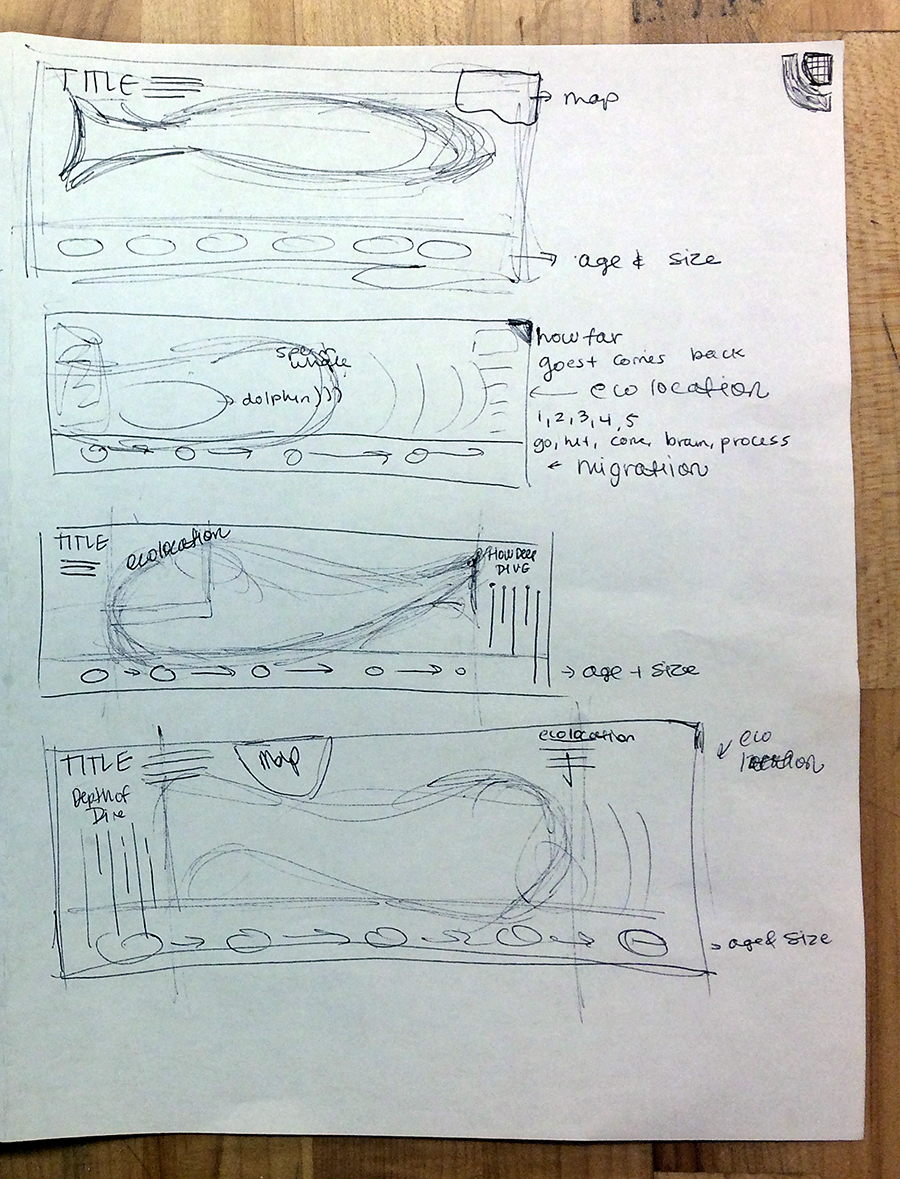

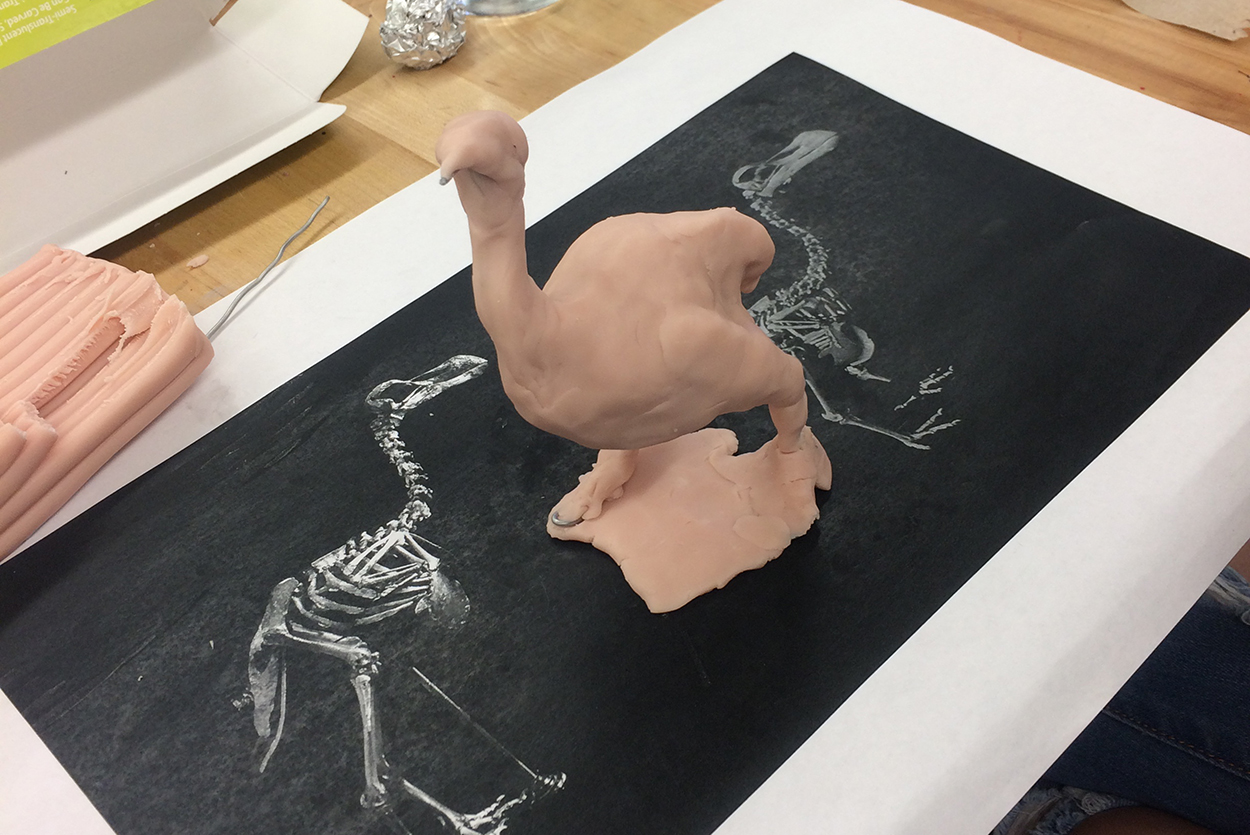

Photograph by Kisha Ravi.

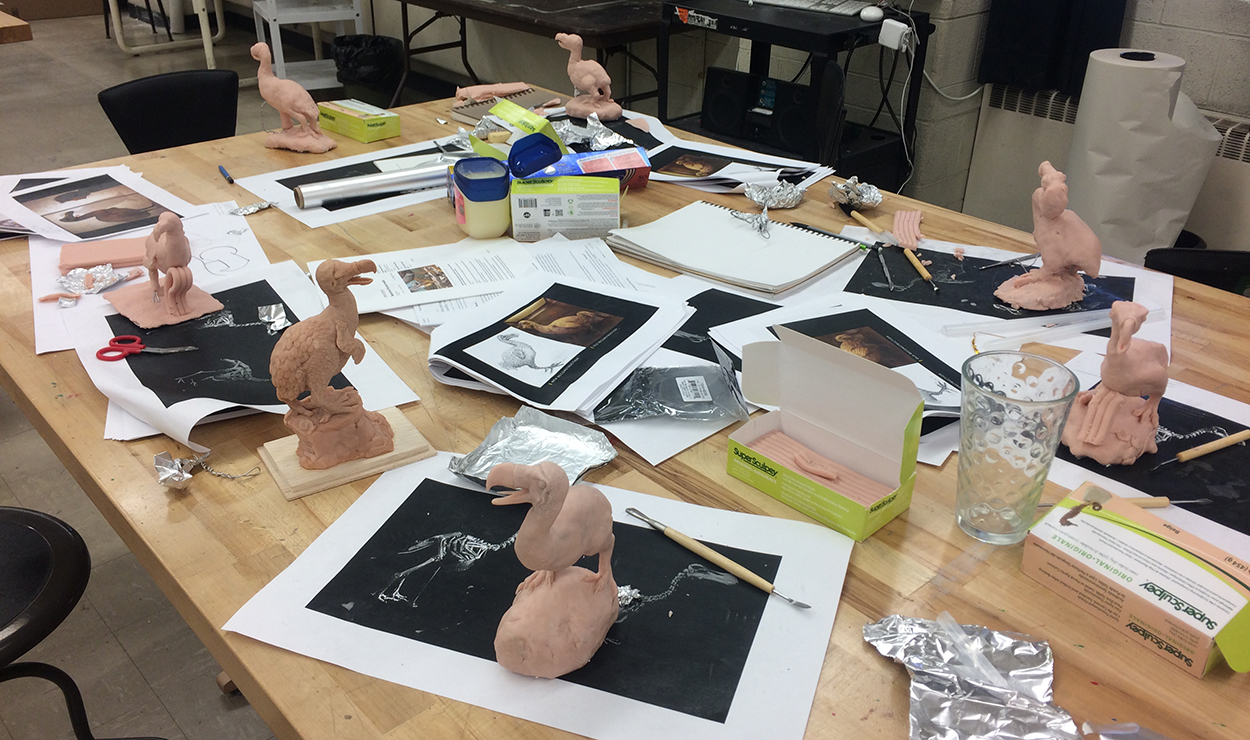

Photograph by Kisha Ravi.

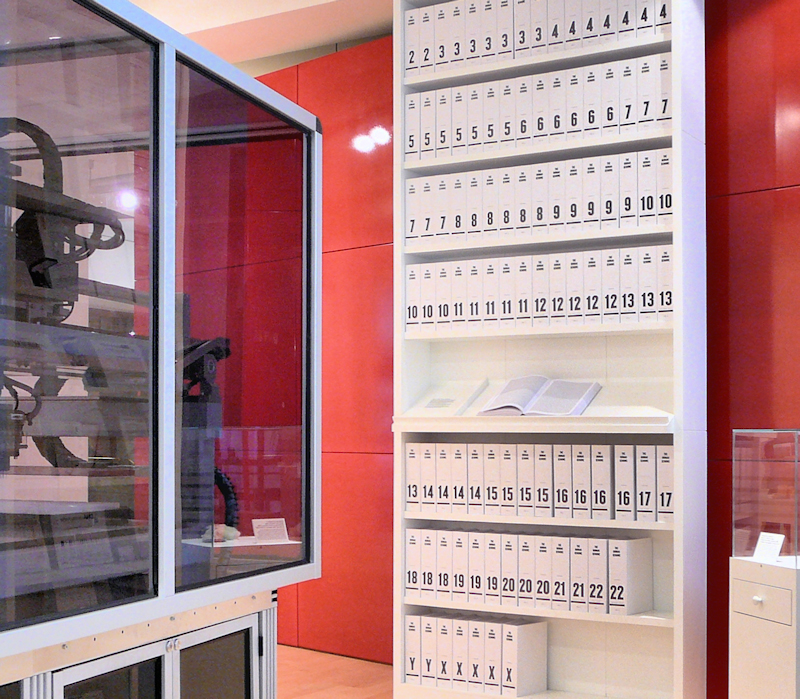

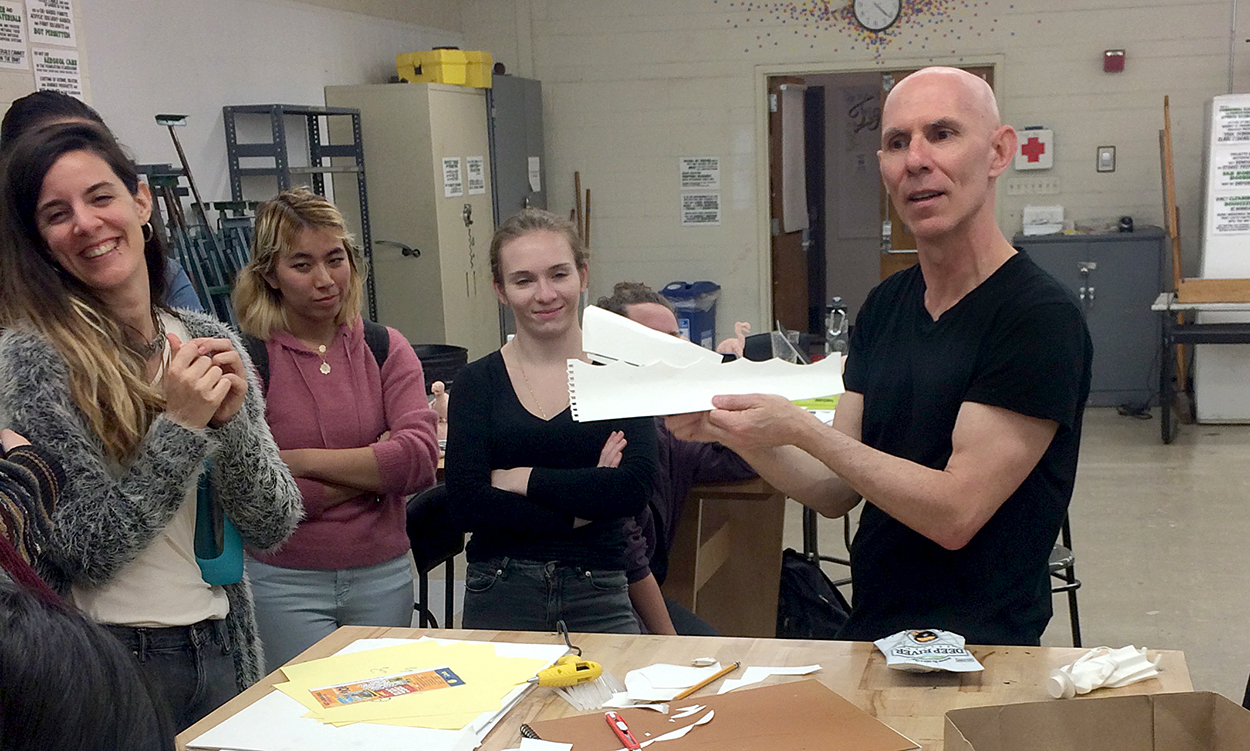

Photograph by Kisha Ravi.

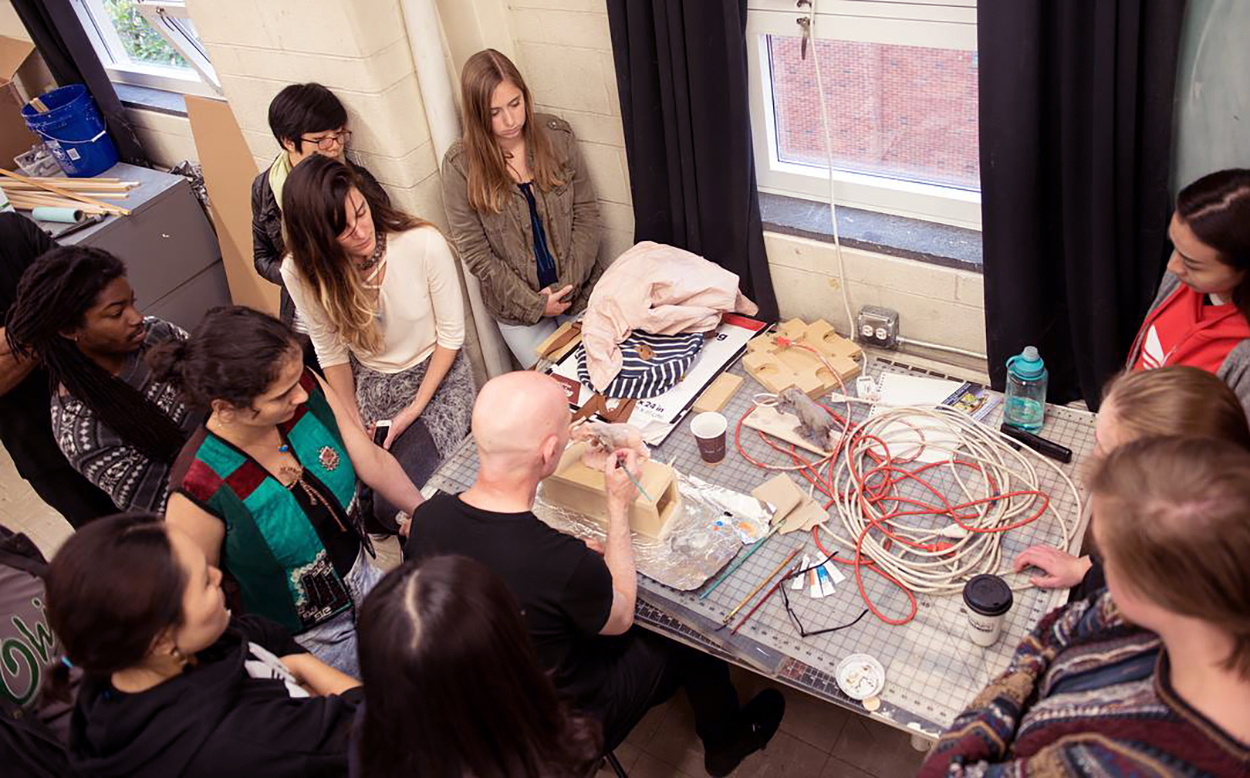

Photograph by Kisha Ravi.